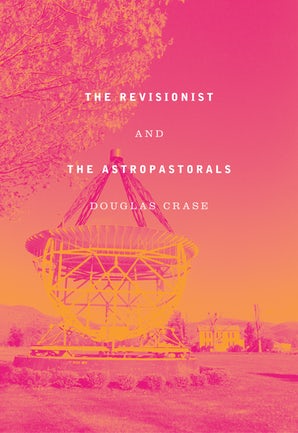

MacArthur “genius” Douglas Crase is best known for his invocations of the American landscape and Transcendental tradition. Out of print since 1987, The Revisionsist has been enough in some opinions to establish him as one of the most important poets of his generation. Its influence persists, says The Oxford Book of American Poetry, as a “formidable underground reputation.” By combining that book with Crase’s recent chapbook, The Astropastorals, Nightboat Books brings Crase’s underground reputation to a wider audience for the first time in thirty-two years.

Details

ISBN: Hardback: 9781643620107, Paperback: 9781643620404

Hardcover, 152 pages, 8 x 5.5 in

Publication Date: Hardcover: Oct. 2019, Paperback: Oct. 2020

Reviews

Thinking here has been arrayed with grace enough to belie its density. Crase’s linguistic domain is at once tantalizingly abstract yet present and palpable. His poems are alive on the tongue while being read and even more so days later, as a recollected fragment surfaces unbidden amid the flux of thought.

Crase renders the most familiar tropes wonderfully strange, these “revisions” of a received canon proving as subtle as they are provocative: “A century Begins,” he explains in “To the Light Fantastic,” “begins because it discovered/ The rights of man, or unearthed light.” Elsewhere, wordplay suggests an ecstatic mystery: “The mitigation remembers the mischief,/ And nothing’s repaired except to engender it/ Different. All things are wild/ In the service of objects.” This expertly framed volume marks a lasting contribution to American poetry.

Substantial poems very much addressed to a listening ear, sometimes identified as a loved-one, and spoken very correctly in a language of description and abstraction with distinct and logical use of figuration.

For Crase, desire is a way of starting again, if not quite starting anew, and it enjoins another longing, or hope: that your strongest attachments needn’t be your most appropriative ones. He dreams – sometimes rhapsodically, at other times ruefully – of acquisition without possession, and the work he adores lives this dream as a kind of calling (‘Anybody knows,’ Stein wrote, ‘how anybody calls out the name of anybody one loves’).

I had heard that Douglas Crase’s only full collection, The Revisionist (1981), was something else, but I was still astonished to encounter its grand, cracked, almanac voice. The Revisionist and The Astropastorals (Carcanet), with a welcome introduction by Mark Ford, reprints all of Crase’s published verse from 1974 to 2000. The Revisionist’s “sinuous, semi-abstract landscape poetry”, as Ford puts it, evokes an America we are still trying to imagine today: “What have we done? Is it true the English / Could have called Long Island as they did, Eden? / Anyway, if the seas keep warming up it will all be gone”.

For various reasons, The Revisionist has stood as Crase’s sole book of poems for nearly forty years, and has long been out-of-print. Fortunately, it has just been reissued in a new edition by Nightboat Books, now gathered together with a more recent work titled The Astropastorals…

The new edition features a valuable introduction by Mark Ford, who reminds us of the “exclamations of wonder from poets and critics across the spectrum when it first appeared,” from Ashbery to Anthony Hecht to James Merrill.

Douglas Crase’s poems are objects of profound and gentle beauty, both in their deliciously poised idiom, and in being monuments to the protean moments of a vast genera of life: civic, environmental, economic, stellar.

Q: An initial question I’d love to know the answer to is the very clichéd: ‘When, how and why did you start writing poems?’

A: Clichéd maybe, but it’s still hard to answer it precisely. A lot of life intervened and I was nearly thirty before I began writing the poems in The Revisionist – although I can’t remember a time I didn’t want to be a writer. My first lengthy attempt was a novel, written mostly on the school bus when I was ten. I grew up on a farm in Michigan and loved the place, the animals, fields and woods, the freedom. So my novel was about a boy and his horse (talk about a cliché) who save their local forest from illegal logging. A favourite great aunt saw this effort and the next year gave me a real book – I would have been eleven – her own copy of Leaves of Grass. It was bound in green with blades of grass in gold along the spine. By the time I’d read as far as the ‘mossy scabs of the worm fence’ I knew the world had changed. I hadn’t heard of sermons in stones or tongues in trees, but from that moment on the whole farm spoke to me in the voice of Whitman. As you would expect, the next thing I wrote was a bad imitation of that voice, my first poem.

Click here to read the full interview!

For Crase, heaven is territory rather than faith, and unlike those in his visionary genealogy his is a “godless distance”, seemingly ripe for exploration.