With mass ICE raids of major U.S. cities promised by an ever-intensifying racist administration, major protests at the nations detention centers after reports of astonishingly inhumane conditions and newly devised asylum restrictions, along with the recent election of Brexit-champion Boris Johnson of the British Conservative party to prime minister of the U.K., this summer has been one fraught with tension along global borders. While we should always be reading up on these particular issues, informing ourselves and each other of their components and consequences, poetry (and literature writ large) maintains its socio-political relevance in doing that very work. What’s more, poetry that works across delineations of language, body, place, and form can inform our understandings of border and passage, as well as their potential breach points. Following that thought, we’ve put together a reading list on this summer’s suitable theme: the border. Enjoy, be challenged, be enlightened, and stay hydrated!

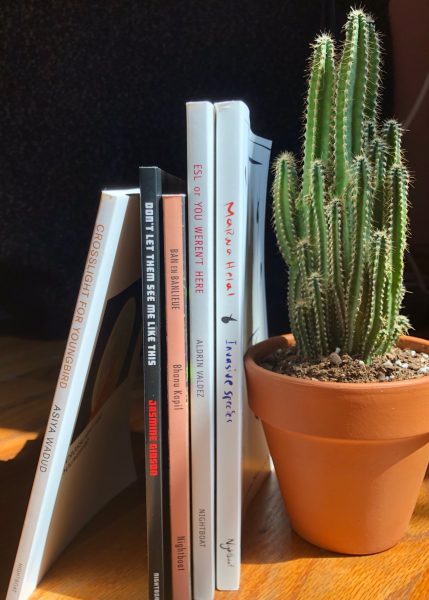

Don’t Let Them See Me Like This – Jasmine Gibson

“Not waiting for racism to die / Instead holding my mouth open / And crushing the state under my mandibles / Letting acidic fists do the rest / Collecting each flag until they become as adorned / As the bodies that continue to die for democracy”

Jasmine Gibson’s poetic delivery is serrated and precise, like searing battle cries delivered from within night-terrors. Here, though, the terror persists in the daylight, which is exactly what necessitates a collection like the one she offers in Don’t Let Them See Me Like This. These poems are poignant, sexy, anarchic, and teeth-bearing, incessantly swinging at the sentries of the state while still taking the time and making the space to plunge the intricacies of abuse fomented by latter. A perfectly urgent collection to begin this list.

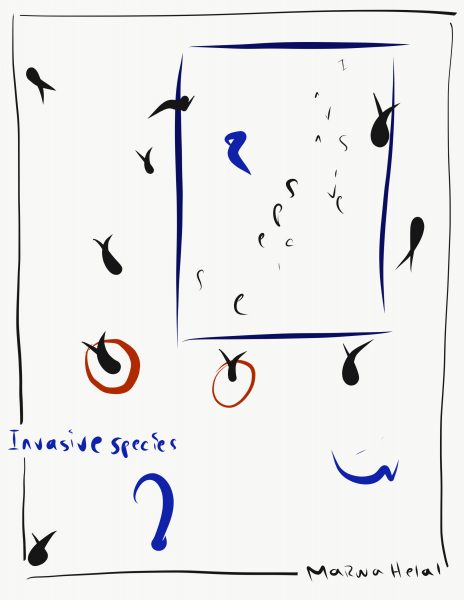

Invasive species – Marwa Helal

“It’s clear the officer has made up her mind before she sees my file. ‘Did you burn your old passports?’ She asks my father. ‘Do you have health insurance?’ She angrily asks my mother. I’m not sure what this has to do with my application. I can’t remember what she’s asked me, what I’m trying to answer when she says, ‘I’ll refuse you for the fun of it.’ My application is turned away (not denied— it’s as if they never saw it, as if I had never been there at all— erased, gone).”

With Invasive species, Marwa Helal wields poetry’s primary weapon against border: the rupture of language itself, the disruption of form. Buttressing the urgency emphasized by Jasmine Gibson, Helal’s debut collection pushes forth a new poetic form she calls The Arabic— a poem to be read right to left, the way one reads and writes the Arabic language—rejecting and collapsing western colonial linguistics on top of itself. Between poems, Helal recounts her frustrating attempts at being granted US citizenship through sections of deeply emotional prosaic memory, along with official documents and letters to US Embassy agents in Egypt, capturing the absurdity of ‘citizenship’ and border, of belonging to two nations and neither at once.

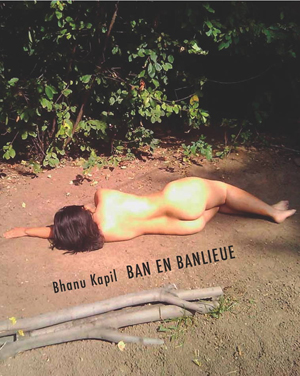

“Ban returned to India, where her ancestors were from, and lay down, as close as she could get, next to the border with Pakistan. A few feet away, under the gaze of a military presence, two guards a few feet away from the Wagah checkpoint, she simply did this (lie down), then stood up and with a long stick torn from a nearby tree, though the area is desolate, marked the outline that was left. Then she re-filled this shape with marigolds … she sat down next to this body and placed a hand on the place where its chest would be, and another upon her own.”

Where do borders find themselves at the place of the body? How might that body share memory and sense with other bodied borders through time? Equal parts transcribed performance and poetic memorial, “Ban En Banlieue” finds Bhanu Kapil navigating that inquiry by way of quasi-protagonist Ban, a brown woman left to die on a side street after a 1979 London race riot. A somatics of otherness, of connectivity and paring, makes this a classic in the study if body-poetic legibility, and ever poignant in a study of both perceptive and physical boundary.

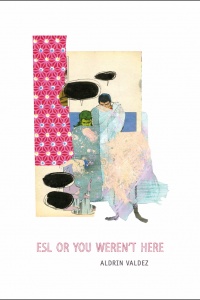

ESL Or You Weren’t Here – Aldrin Valdez

“They-child, / shaking the shadows for a familiar body, changing you / from someone I could get to know / to a person who is about to leave / or has already left. / Hoy bata! I tell that self, you try so hard not to feel / abandoned. / & I remember / them, queer, bakla, phaeton-like, staring at the Manila sun one morning / as though they could see more than its yellow haze. / Perhaps, / as in darkness, searching / in light for a body their body / remembered.”

A finalist for the 2018 Lambda Literary Award in gay poetry, Aldrin Valdez’ debut collection has received much attention and celebration in the past year, and for good reason. Through an inescapably palpable tenderness, Valdez writes through their childhood kinships, particularly mourning the loss of their Nanay shortly after immigrating to the US from The Philippines, and the uniquely multifaceted blitz of queer pubescence in a new, overbearing American culture. Valdez highlights the border as filter—of language, name, gender, familial affinity—and convolution, a complete disarming at worst, of ones tools of self-articulation.

but it’s a long way – Frédérique Guétat-Liviani, trans. Nathanaël

“it’s because of the fence / water passes through the fence / it makes a shadow / and it makes a sun / water / it isn’t hard / it can pass / through the fence / there are men / in the water who die / after / they won’t / die anymore / they will live”

A reading list on borders would be palpably incomplete without this series of poems by the Algerian-born, Moroccan and French-repatriated poet, Frédérique Guétat-Liviani. Translated from the original French by fellow Nightboat author and translator Nathanaël, this collection is a landscape in itself, itinerant and winding, tracing the contours of walls and pores in language and land. These poems contain and proliferate a legion of voices, all transcribed from deliberate encounters with folks living in three different housing projects in Avignon, France. Family and love act as lenses through which permanence and permeability are surveyed, along with the translation of relations, of body and sense of place, across home and adopted cultures. Complete with the original French manuscript and a closing interview-like section where the author sheds light on the aforementioned encounters and the place of author within their transcription, this is a brief but loud and choral collection that can’t be overlooked.

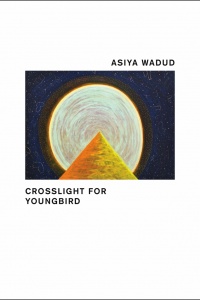

Crosslight for Youngbird– Asiya Wadud

“imagine sappho doubling down on / an uncertain patter / imagine sappho in a life vest no love / imagine bunions heel / spurs and hammertoe imagine sappho in / a diving bell port starboard lesbos / imagine sappho as the sun / expect the sun to run aground”

We could say this collection is about the refugee crisis—and it very much is—but it is also about a light which can be called God, and where it falls and falters. Wadud’s prose-poetics abound in assonance and, winding, constellate the many fronts of displacement, from Scandinavia to Greece and then from the planetary to the astral, following that aforementioned light. Water, particularly saltwater, is nearly omnipresent, as are bodies and boats and sand, constantly reminding us of the simultaneity of serenity and emergency, of light and shadow, call and response.