Winner of the 6th Annual Believer Poetry Book Award

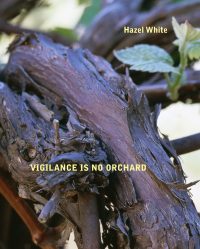

Some Beheadings

A stunning debut collection that examines the geophilosophy of lyric poetry

$9.99 – $15.95

Additional information

| Weight | 0.31875 lbs |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 5.4 × .3 × 7.4 in |

| Format | eBook, Paperback |

Here the “beheaded” poet displaces her mind into the landscape, exploring territories as disparate as India’s Western Ghats and the cinematic Mojave Desert, as absurd as insomnia and dream. Some Beheadings asks three questions: “How does thinking happen?” “What does thinking feel like?” “How do I think about the future?” The second question takes primacy over the others, reflecting on what poets and critics have called “the sensuous intellect,” what needs to be felt in language, the contours of questions touched in sound and syntax.

Praise

Dear Aditi, I did receive “Route Marienbad”. Read it. Had the feeling I was discovering a real poet. A wonderful feeling. I hope you keep this “innocence,” this directness, this genuineness. Bonne chance

One way to think of these crystalline (brilliant, light-filled, prismatic, latticed) poems is as interlocking gears in a jeweled surrealist watch that has been put to bed in a transparent glass case and yet, day after day, it refuses to sleep. The parts can be seen continually moving, although at variable speeds: as soon as one goes faster, another carefully slows its pace. Each element is mesmerizing in its elegance. To attempt to deconstruct these poems would be to blow them apart. That said, what can be said is—They are utterly contemporary. They are deeply intimate. They are the lashes of a forest of thought.

If John Ashbery’s Some Trees marked a new beginning for modern American poetry, Aditi Machado’s Some Beheadings renovates the poetics of indeterminacy for our transnational continuous present. Tracing migratory routes through the thickets and deserts of signification—from the Western Ghats to Marienbad and beyond—Machado arrives at something like a spiritual allegory for the disenchanted. “Grace not of but as / god,” is the subject of her post-universal grammar, “that unusable concept / used in excess.” The grace of such work opens new prospects—or prospekts?—onto identity’s imperium: “& I is an orient in the sense that all things wend toward me.” Yet the spectre of sovereignty, in Machado’s literary imagination, remains ever haunted by its own linguistic predication. “I have lived,” observes this incomparable elegist of belonging, “is a way of saying something ceased.”

Details

Reviews

Machado’s steadfast and rigorous debut exists at the intersection of language and place, where thinking takes the shape of a tree or a thicket of “florid logic” that grows and branches in multiple directions at once. “I describe my day to myself as if I were perambulating through infinite foliage,” she writes. The images take readers across time and space: to fields dotted with grazing ruminants; deserts whose “labial dunes” double as runes; and, in an oblique reference to the film Last Year at Marienbad, a Marienbad where a “single baroque animal/ opens a pomegranate” and “ancient civilizations spill out as red beads.” Though the focus of the text meanders, the first-person perspective offers a sense of immediacy; in other words, however disembodied the thinking, and however omnidirectional the thought, the speaker grounds ideas with notions of physicality: “Can you wake up/ from a sentence like/ you wake up on the porch?” Machado’s luscious descriptions—themselves “a mild decadence, an explicit/ industry as that of bees”—exude a palpable strangeness, and the speaker welcomes constant change and movement without requiring a resolution. The result is a labyrinthine sensorium where thinking about thinking generates ever more pleasures. (Oct.)

It’s hard for me to describe how excited I am about this book. Machado’s work is searing in its search and interrogation of the self, of faith, and of how these things relate to the world. Her poetry burrows within the mind and the soul and breaks open into the expansiveness of the worlds contained within. This is an important book; reading it will undoubtedly remove your head.

Maybe a writer is someone who describes the world while a poet defines it. Aditi Machado has a profound gift for giving new shape to familiar concepts: “When a body desires / its continuance / that is need. / When it desires / its dissipation / that is want.” Her poems are reminiscent of Rae Armantrout’s for their subversive, cerebral quality; she plants an image in the mind, then no sooner erases it. “The whole village was there, minus its people.” The title of her collection, Some Beheadings, stretches a dark shadow over these lyrics. Unrest is always close at hand: “A mirror / brightens the fascist / in me.” And yet, even as things appear grim, the poet finds sensory pleasure in wordplay: “How long before / I walk into the sea remembering / what the kelp felt like: like felt.” Machado not only elegizes the dying ocean but renders her own words water-like; it’s as if that phrase (“felt like: like felt”) is itself a reflection off the sea’s surface. It’s thrilling to read a language poet of such powers. Machado offers a fresh encounter with a world we thought we knew. “Every day I wake I see sun, / it’s blue.”

Some Beheadings shakes the gravity of beheadings with the offhandedness of some, telling you instantly that the ground ahead will be uneven and arresting.

Minimal, unique, puzzling, and beautiful, Machado’s Some Beheadings, confronts logic while massaging the heart. No matter how heady the words fall on the page, there is always a sense of the author holding your hand in the rain, asking difficult questions while wandering without destination, but always holding an umbrella over your head to keep you dry

To be able to see and understand herself, Machado has to leave herself, behead herself—the violence that the lyric does when it turns a particular flesh-and-blood person into an abstract, disembodied vocal entity. Machado shows what it is like to dismantle the dismantler. In these poems, the dismantler is the poet, whose world is ruined as soon as they start to sing. Whose very song is a ruining.

“In a metaphor, the vehicle is a stand-in for the tenor; we always know which term is “real,” which merely “figure.” Here the relationship between the routes and vistas of the natural world and those to be found in and through the sentence or line is not so hierarchical. Rather, world and word are mutually productive. Machado places herself between them, mediating and noting their interdependency…Poetry is the one genre of writing that can give priority to the non-sensical and overtly sensual ways that language makes meaning. Machado delights in the slippages between words, in the sounds they make together, and in their rhythmic play.”

This ability to lose the everyday self would seem at odds with the interesting, which asks that the looker or reader or audience barely budge from their seat. Machado draws on this most classic of poetic functions — loss of one’s self – by coordinating the interesting and the sublime, as received categories, as received circumstances, so that exhilaration happens. It’s metacognive and it’s not.

What this book reveals is a mind at war with itself; which is to say, a mind. Part of Machado’s (ambitious) project includes a close investigation of the subject, how it thinks, what it tells itself about itself. Such a project is vital today, when some of the most basic and unanswered questions (about our relation to ourselves, to Eros, to sex, to other beings, to landscape) continuously churn back to the surface, often violently.

Machado’s poems make the reader reconsider just what the line between speaker and poet looks like, and whether the poetry world at large needs to reconsider whether that line is just a bit smaller than we usually think. If all of life is a textual experience, if our actions are a form of writing in and of themselves, then we are all constantly speaking and having poetry written around us.

‘When I speak,’ Aditi Machado declares in the first lines of ‘Prospekt,’ ‘the fascist in me speaks.’ Such boldness is characteristic of Machado’s first collection, . . . and signals a poet willing to implicate herself in the disturbances that surround her. If she is going to make the reader uncomfortable, Machado shows admirable solidarity by joining in the discomfort.

Aditi Machado is an Indian poet whose books include Some Beheadings (The Believer Poetry Award, 2018) and a translation of Farid Tali’s Prosopopoeia. Her two most recent chapbooks are …