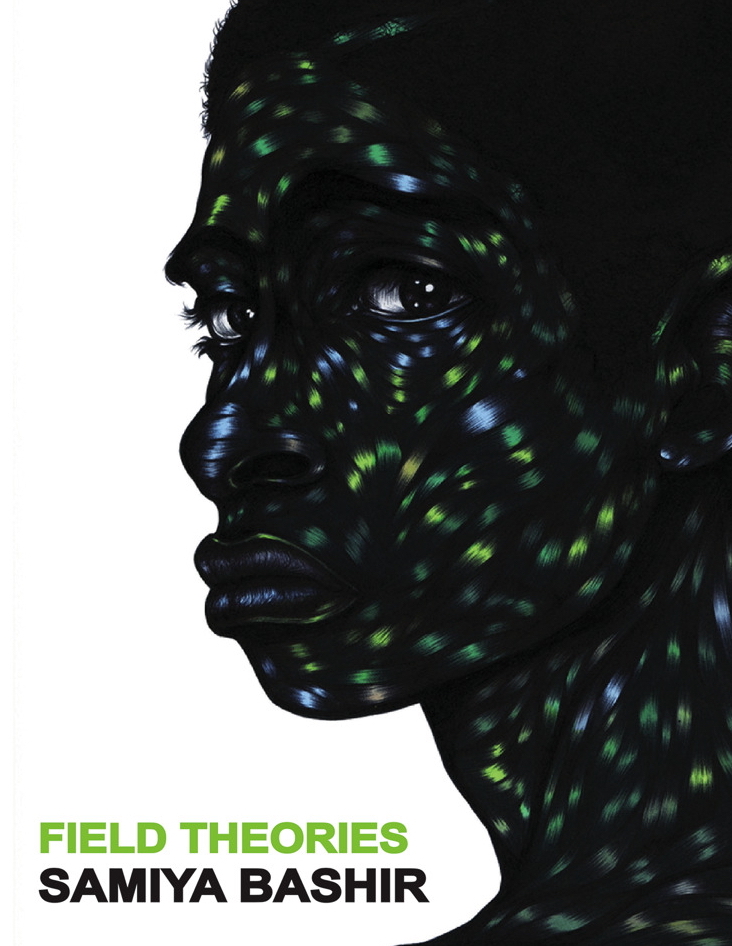

Field Theories wends its way through quantum mechanics, chicken wings, Newports, and love, melding blackbody theory (idealized perfect absorption vs. the whitebody’s idealized reflection) with live Black bodies. Woven through experimental lyrics is a heroic crown of sonnets that wonders about love, intent, identity, hybridity, and how we embody these interstices. Albert Murray said, “The second law of thermodynamics ain’t nothin’ but the blues.” So what is the blue of how we treat each other, ourselves, and the world, and of how the world treats us?

Reviews

It’s easy to find poetry in science, from the ring of Latin names to the construction of an elegant theory. It’s a harder thing to find science in poetry. But that is the genesis of Portland poet Samiya Bashir’s book Field Theories, where poems titled after scientific principles like ‘Planck’s Constant’ and ‘Synchronous Rotation’ plumb the space where theories collide with real life: from the back seat of a taxi to jazz clubs, early morning cigarettes, human fables, gun violence and Groucho Marx.

Starting with her title, Field Theories, Samiya Bashir challenges the vocabulary of science, finding inflections and echoes within that vocabulary of the long and brutal history of race and racially based economic exploitation in the U.S.A. When used within the respective sciences of physics, psychology and social science, the term ‘field theory’ (singular) has specific meanings. ‘Unified field theory,’ in particular, coined by Albert Einstein, refers to the attempt to find a single framework behind all that exists (gravity, however, continues to escape this effort). But by changing ‘theory’ to ‘theories,’ (plural) Bashir subverts that idea of a singular framework to reveal the multiplicity of reality: where there is one reality there will be other realities told in various forms, splitting the dominant narrative into a prism of narratives. In contrasts and convergences, she questions history (histories) and how it is (they are) articulated in even the most objective of ‘fields.’ In fact, ‘field’ itself is a loaded word within slavery’s context, indicating enforced agricultural labor.

At first, it may seem surprising that this energetically in-your-face collection references physics. But when Bashir (Gospel) notes of thermodynamics, ‘When Albert Murray said/ the second law adds up to/ the blues…/ he meant it//… more how my grandmother/ warned that men like women// with soft hands,’ you see where she’s going. ‘Planck’s constant’ denotes holding to others as we climb to get ahead; ‘Ground state,’ a surge toward intimacy; and ‘We call it dark matter because it doesn’t interact with light,’ America’s increasing xenophobia. Thus does Bashir sort out life’s demands, periodically grounding her exploration with references to African American legend John Henry and his wife, Polly Ann. VERDICT Interesting work; anyone who can combine woolly mammoths and the lyric ‘I’m gonna be your number one” in one poem knows her stuff.’

In this electrifying collection, Bashir co-opts the vernacular of thermodynamics to generate clever, ambitious poems: ‘We call it dark matter because it doesn’t interact with light’; ‘Blackbody curve’; and, of course, the titular ‘Field Theories.’ Bashir plays with double meanings, unusual narrative structure, and experimental visual arrangements, such as ‘Law of total probability,’ about an office shooting, from which conspicuous circular portions of the text have been removed. In another, ‘Blackbody radiation,’ the text has been scrambled on the page, thrown together with mathematical signs and symbols. The book alternates between these science-inspired, avant-garde pieces and an extended sequence about the legendary John Henry. By pairing this monumental black figure with the terminology of scientific fields that have been defined by whiteness, Bashir creates a jarring, resonant contrast in this substantial gathering. The result is a dynamic, shape-shifting machine of perpetual motion that reveals poignant observance (‘Even Jesus let / his baker’s dozen fend / for themselves once’) and verges toward hallucination (‘We blow smoke rings and shape them into big beaned cloud gates’).

In her third collection, Bashir (Gospel) displays an intriguingly multivalent approach to the objectivities and subjectivities of black experience reflected in her multimedia collaborations. A series of recurring ‘coronagraphs’ become a tunnel through which the figures of John Henry and his wife Polly Ann speak, forming a sonnet crown that brings new life to an American myth. They are interspersed with four sections structured on the laws of thermodynamics and bearing voices of denizens trapped in a capitalist matrix, ‘An anthropocene/ of wannabe hepcats” who ‘pay// defense department rates/ for a sandwich; unremember// memorable jingles.’ Bashir’s experimental visual gestures, such as a bullet-hole riddled prose poem on the law of probability, resonate as bluesy meditations on cosmic entropy’s presence in the irreversible occurrences of American lives. While fans of Kevin Young will appreciate the pop of unexpected end rhymes and a present-tense narrative impulse, those of the more associative Ashberian school will enjoy such playful titles as ‘Universe as an infant: fatter than expected and kind of lumpy,’ which features a private visit with Groucho Marx. Whether depicting the faces of marginalized citizens at late-night truck stops or cross-sectioning ‘bloodstreaks through musculoskeletal structure,’ Bashir positions the slings and arrows of black American life as both empirically observable and available for radical, and movingly layered, interpretations.

Bashir hits a heightened sense of observation in her writing, born of a need to be vigilant as a woman of color. ‘I’m born and raised in America, so my race, my gender, my class—these things have been enforced as a part of how I move in the world, how the world experiences me and responds to me, since birth. It means that I’ve had to learn so much for simple survival reasons,’ she says. ‘We talk sometimes about how white people don’t necessarily understand us as black people, but the flip side is not true. We have to understand everything about them before we leave elementary school if we want to live.

Field Theories pivots around this central theme, that the black body—scientifically speaking—is an idealized physical body that absorbs (my italics) electromagnetic radiation, while a white body reflects (my italics) all rays completely and uniformly in all directions. It’s how Bashir renders that theme which makes this collection worth reading.

What makes this work particularly remarkable and interesting is the way that, even as the poems demand that you reflect on and identify your own position (one possibly outside the first-person plural position they mark for themselves) they allow a movement-alongside and sustain a relation, one whose terms include an awareness of the multiple kinds of fields the poems work to make perceptible. You just have to stand, as a body, aware of the terms of the fields acting on you, to do so. Overall Bashir’s book is beautiful, thoughtful, graceful, and strange. It is a book that makes the conditions of sense-making, the conditions of life in a system with an inherited racist history, the conditions of formal movement in a poem, available to sense in new ways.