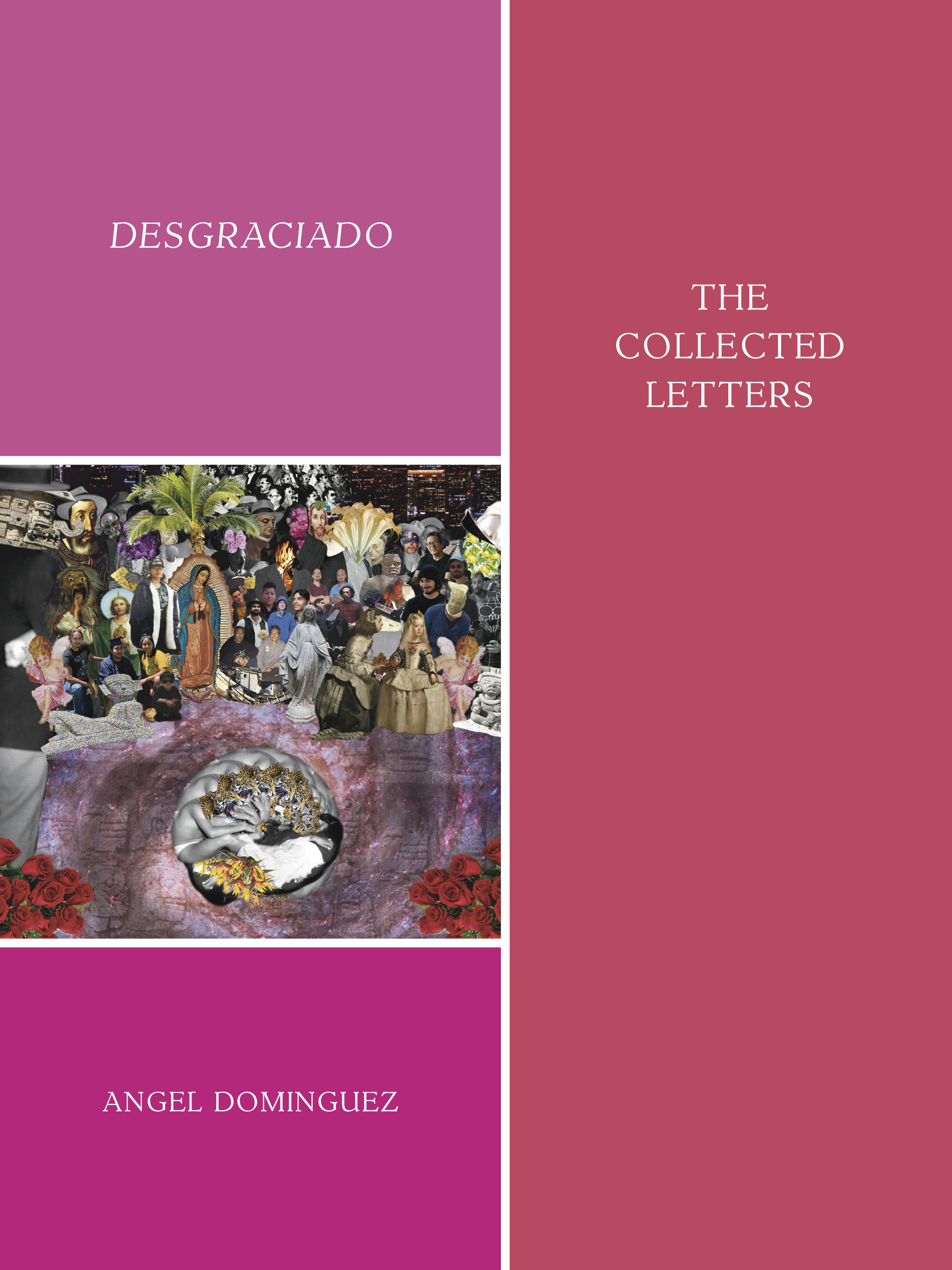

In DESGRACIADO, Angel Dominguez navigates a visceral constellation of language and memory, illuminating the ongoing traumas of misremembered and missing histories, and their lasting impacts. Dominguez unravels a critical and tender language of lived experience in letters addressed to their ancestral oppressor, Diego de Landa, (a Spanish friar who attempted to destroy the written Maya language in Mani Yucatán, on July 12th 1562), to articulate an old rage, dreaming of a futurity beyond the wreckage and ruin of the colonial imaginary. This collection doesn’t seek to heal the incurable wound of colonization so much as attempt to re-articulate a language towards recuperation.

Reviews

By treating the figure of Diego as both enemy and lover, Dominguez attempts to subvert his enduring influence, holding the colonizer in his own purgatory… This is an intimate embrace of personal struggle, but Dominguez also takes many opportunities to highlight the resiliency of all those who were colonized across centuries of violence.

With Desgraciado, you deploy a stripped-down understanding of performance that is simply survival, both in terms of your money and creativity. But also, survival in the sense of your ancestral survival, as refusal.

Our greatest epistolary poet seeks catharsis and self by addressing a genocidal colonizer directly.

-Henry Hoke, BUTT Magazine

Dominguez writes with a profound intensity. […] Common themes of colonization, racism, and homophobia permeate the collection and descriptions of violence sit uncomfortably alongside images of flowers and nature. But this discomfort is vital to the collection’s impact.

Angel Dominguez has given us a weapon, a codex with which to fortify and record a new communication.

With repeated images of fire and ghosts, and all the echoes of our colonized world, Dominguez pens the most tender vengeance.

I think in all honesty the most challenging thing about writing this book was realizing that I was fighting a fight I could not win with poetry. Decolonization is a verb. An ongoing process and not an imaginary destination.

Despite the flames, throughout Desgraciado, Angel Dominguez communicates through channels of water, and conjures all of nature’s elements: the life-giving and destructive, invasive and sacred.

There is such an intimacy and an insistence through these letters, writing through loss and a layering of trauma, from the historically-lost to those still to come… Writing out a lush and insistent lyric, and an open-hearted and insistent engagement, with passionate resolve, Dominguez writes as a way to attempt to reach back through these layers, through the past to seek out these paths, these truths.

Rather than retell the colonizer’s version, Dominguez challenges the notion that history is in the past: “[history] is this living thing that we engage with.” The violence of the genocide is detailed in the letters, a violence, Dominguez argues, that should not be forgotten. “My grandmother remembers,” reads one of the letters. “The temples may be ruins but we…We are alive.” This collection does not seek to resolve or ‘forgive and forget’ the past, calling instead for descendants of oppression to expose and retaliate against systems that perpetuate that oppression however they can. For the narrator, that is through writing: “Language is a weapon…Sometimes, healing is not what we need.”