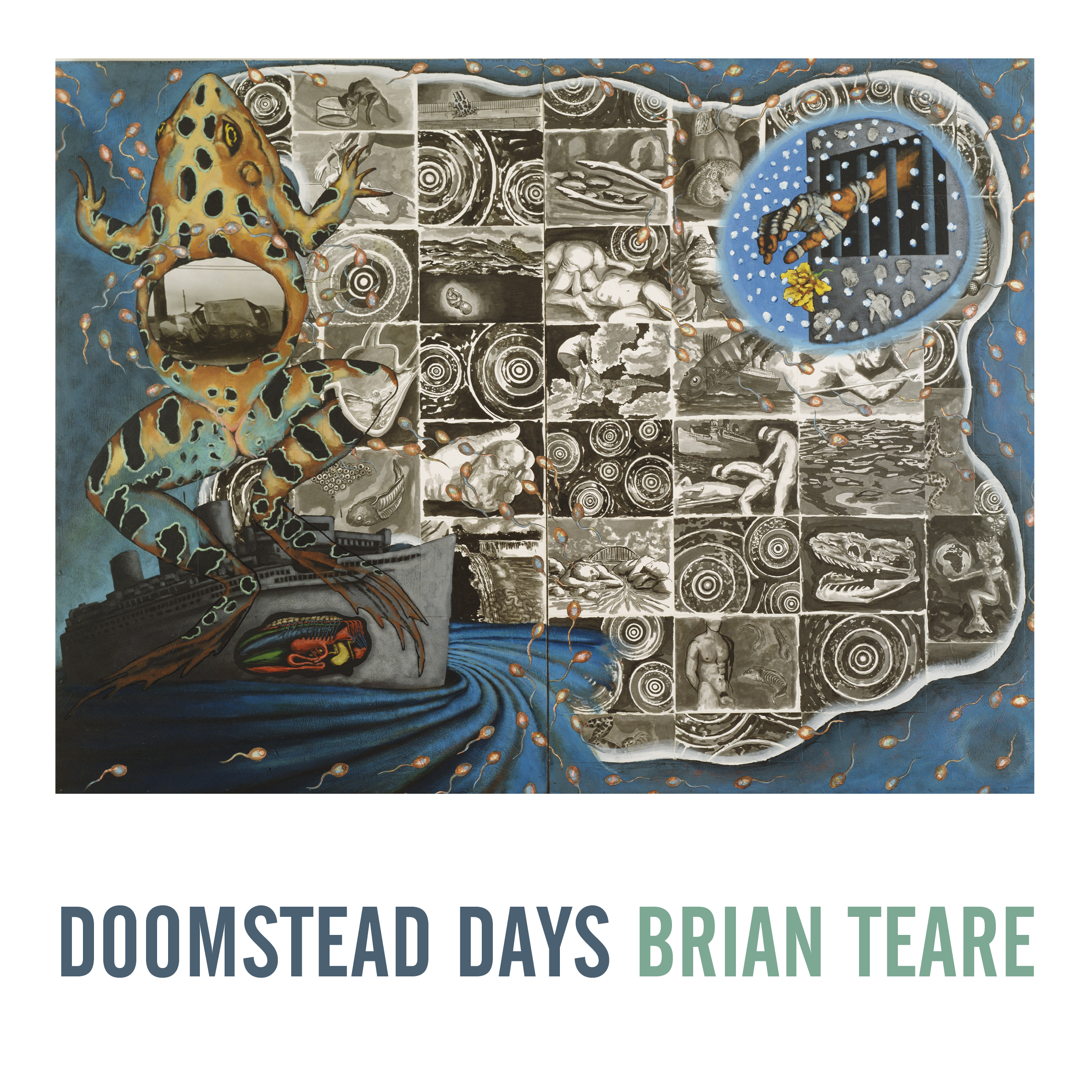

Doomstead Days is a lyrical series of experiments in embodied ecological consciousness. Drafted on foot, these site-specific poems document rivers, cities, forests, oil spills, mountains, and apocalyptic visions. They encounter refineries and urban watersheds, megafauna and industrial toxins, each encounter intertwining ordinary life and ongoing environmental crisis. Days pass: wartime days, days of love and sex, sixth extinction days, days of chronic illness, all of them doomstead days. Through these poems, we experience the pleasure and pain of being a body during global climate change.

Reviews

The poems feel solitary but intimate: Teare’s voices let us weigh the insoluble questions of how to live as an ethical being in the face of violence and environmental collapse.

To enter the world of Brian Teare’s Doomstead Days is to enter into an experience where the binary between world and body dissolves almost completely, “to vanish outward,” as Teare says.

Brian Teare’s Doomstead Days (2019) is a set of verse walks that he takes in nature, a nature that he sees with rare precision, humor, and depth. But as much as he bemoans what humans have done to nature, he also sees himself as a culprit.

Doomstead Days is a book very much engaged in the large canvas, experimenting with short lines and short sections across expansive sequences, collected here as a sequence of poem-sections. Teare’s experiments in rhythm and meaning coincide with how the poems flow across the page, whether poems constructed using left-margined short, accumulating lines, a sequence of two or three line stanzas that flow back and forth across the page, or a sequence of three couplet stanza-squares, one to a page. “[S]ometime the image,” he writes, in the poem “Toxics Release Inventory,” a poem subtitled “(Essay on Man)”: “seems like the first frames of film / before the horror [.]”

Biological and ontological, these are the questions of our age, or our days as Teare has it—a reminder that human nature has always been tied to Nature. That thread is unraveling in the world we’ve made, and to be apocalyptic is to be realistic. What’s to come is “a kind // of life not yet / legible to us,” but Doomstead Days is Teare’s beautiful and brave attempt to read that life, write that life.

In this, Teare’s sixth book, he uses his astonishingly precise verse to elucidate what he thinks is perhaps the greatest cause of our current environmental crisis: the ability for humans to see themselves as somehow separate from the world. This artificial delineation has been the frame over which some of the greatest tragedies of humanity have been built including imperialism, war, genocide, and slavery. And while Teare interrogates all of these in Doomstead Days, the book itself is undoubtedly a new and essential addition to the growing library of eco-poetics.

In Doomstead Days, the celebratory and the harrowing, the healing and the violent, the fertile and the impotent are “equal all.” To say that Teare’s poems reside inside — and embody — bewildering equations is to pinpoint one of the ways he allows you to re-experience the world — to see everything anew…

How do we live among the wreckage of what’s been spilled? Syllables hum with the felt sense of the poet, whose sweat wets the notebook as he walks. Teare has composed lyrics as formally meticulous and sonically aware as they are expansive, pleasurable, and unforgettable.

Teare’s poetry matters for the depth of what it can bring to sensual life. Readers will be grateful to encounter our neurotic, medication-swollen, late-capitalist mess of an era alongside a sensibility so evocative and intense.

Given the havoc of climate crisis around the world, Doomstead Days is an all too timely book. While its title may invoke a sense of doom, Teare’s poems accurately report what he finds on his walks, and yet at the same time inspire us to act with tenderness.

…You can bet a Teare poem is gonna be about one of three things: reading, walking, or fucking. A poetry of encounters: page, world, partner.

Brian Teare interviewed by Richard Sharpe as a National Book Critics Circle Finalist for The New School

RS: Did you intend for this poem to illustrate the world as an entity that retaliates against those who abuse it?

BT: It’s because of being’s ability to engender, its astonishing capacity to keep going, that water and land remember us too well. And it’s because of their memory – which will outlast each of us – that we need to take care.

Erica Bernheim e-mail interviews Brian Teare for The Adroit Journal:

BT: I don’t believe in ‘form.’ But I do believe in forms, that each poem, like each body, is its own occasion, both deeply willful and totally contingent.

Teare suggests that if there’s hope, it lies in attunement to the fluid gender of the Anthropocene phenomenological world and in unconventional—queer– ways of loving the world’s flesh. Attentive walking in our inescapably impure surroundings may help cultivate both.

Composed of eight long poems, Doomstead Days is rooted, for the most part, in walking excursions through both natural and built environments… The length and formal intricacy of many of these poems engenders a discursive lyric that is sometimes diaristic, at other times documentary.

Teare’s poems explore the toxicity and slow violence of environmental degradation across vast spatial and temporal reaches, using both wide-angle and microscopic lenses. They deal with landscapes and watersheds, histories and statistics, but they also present sensory images gathered through bodily encounters—the crush of pine needles, burning thighs, sticky resin, wind. His lyrics unspool in ambulatory fashion, employing syllabics to create a pedestrian rhythm as their lines trail over the extra-wide pages. Some carve a river across the blankness; others stream downward in long, thin strips.

[A] lyrical romp through our connection to land, water, and each other. Water flows, gender is fluid, and the rigid binaries of our imaginations dissolve.

Teare navigates connections between place and self, and somatic experience and language, while highlighting the human-made toxins ubiquitous in our bodies and the environment. His line breaks isolate the individual components, like when he describes the spine’s “molecules locked in,” then breaks before the next image, “degraded matrices.” Or a few lines later when he writes: “medicines I need // & pesticides I don’t.” The break between “need // & pesticides” describes both the necessary and unwanted substances in the speaker’s body, but even those needed “medicines” contribute to the “pharmacopeia / of harm for riverine // species.” The break between “riverine” and “species” emphasizes both the river as an entity in its own right and the “species” that reside there. As the lines accumulate and cascade, like the “brook thrown downhill / by its own force,” the pervasive intertwining of body, toxin, and environment is foregrounded. The depth of meaning Teare creates with his line work is all the more notable because of the syllabic restrictions in the form.