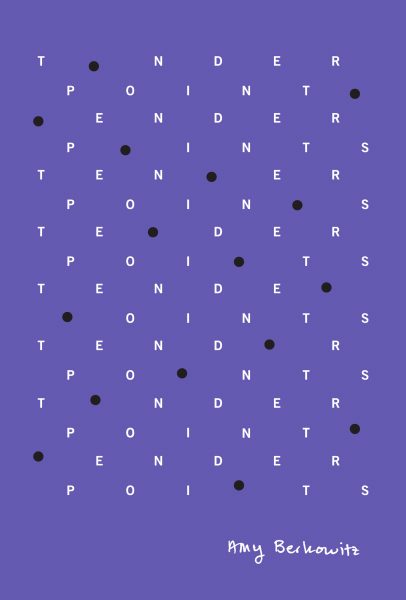

Amy Berkowitz’s Tender Points reads as a lyrical essay, with fragments of personal anecdotes, philosophical thought, excerpts from online forums, and as a slow unfolding and investigation into two interconnected traumas. Berkowitz’s prose and its form evoke the discrepancies and uncertainties of living with an “invisible” and “mysterious” illness. Probing the realities of such an existence, a simultaneous tenderness and toughness starts to manifest through the book. The intimacy of the reader’s experience is incomparable: beginning with Diane di Prima’s “I have just realized that the stakes are myself,” the reader realizes that the process of self-acceptance and living with a body that’s in pain is a continuous endeavor, that dismantling systems of oppression is a communal effort. I had the pleasure of talking to Amy about the themes and references behind her work, as well as the importance of building community while experiencing uncertainty. Read on to know more!

—Sahar Khraibani

Sahar Khraibani: Tender Points was first published in 2015, and this new edition, published four years later, includes an afterword where you talk a little bit about what changed between the first edition and the second. It seems that in the process of writing and researching, you were simultaneously, and perhaps unconsciously, building community. What does that mean when it comes to slowly dismantling systems of oppression and our culture’s hypocrisy towards authority and pain?

Amy Berkowitz: Well, I think it’s a lot easier to work towards dismantling systems of oppression—or even recognizing systems of oppression—when you’re not feeling alone. As I say in the afterword, when I started writing Tender Points, I was isolated from other chronically ill people, so my pain felt like a personal problem I needed to sort out (and that’s why I started writing the book!). I felt like I was the problem: I couldn’t work, I couldn’t get out of bed on some days, doctors didn’t really understand what was wrong with me, and while the connection between my assault and my pain was totally obvious to me, I doubted other people would understand. But then when I started reading other peoples’ accounts of disability and illness and links between trauma and pain and so on, I realized I wasn’t the problem; the problem was capitalism, the problem was the patriarchal bent of western biomedicine, the problem was the prevalence of sexual assault and our culture’s reluctance to talk about it.

I think about the poem “Crip Fairy Godmother” by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha a lot, because it captures that liberating feeling of realizing that you are not the problem and realizing you are part of something bigger, part of a community: “You are not an individual health defect,” she writes. “You are a systemic war battalion / You come from somewhere / You are a we.”

SK: I felt a simultaneous tenderness and toughness throughout the text. There is a sense of trying to grapple with your own authority regarding your own experiences, anger translating to shame and self-punishment, and then a soft tenderness, an acceptance of living with a body that’s in pain. Did the process of writing this book mirror any of these feelings?

AB: My process with Tender Points was one of accumulation. I accumulated thoughts, feelings, quotes, and hyperlinks into the infinite void of a Google doc. When a feeling was hard to sit with—when it made me feel too much shame or placed me dangerously back into the moment of my assault—I hit return until it disappeared into the doc. The infinite void of the Google doc welcomed all feelings, all content. There was room for everything.

I don’t know how much I grappled with my own authority. The book is basically an assertion of my authority regarding my experiences, which is a sort of an unusual kind of authority: an authority that’s uninterrupted and unperturbed by the gaping holes in my story (“mystery” diagnosis, incomplete recollection of abuse). Like many people with recovered memories of childhood sexual abuse, I struggled to feel fully confident in my account of the incident—so many details were unavailable to me! But at the same time, I was certain I’d recalled a memory. I was certain my recollection was imperfect and lacking, and certain that this lack was an invitation to doubt.

I think tenderness is what allowed me to undertake this project from start to finish. It takes tenderness to sit down with yourself, all your imperfections and contradicting evidence and unreliable narrator-ness and say I believe you, your story is worth telling. But then again, isn’t that toughness? It takes toughness to keep working on a project about two awful things that happened to you, two awful things no one wants to believe, to insist over and over that they happened, that they were connected, and here’s evidence, and here’s how, and here’s why it’s important.

I’ve just now decided tenderness and toughness are the same thing.

SK: What I appreciated in this work is the fact that you vocalized the lack of expectations of culpability in our patriarchal system. Starting with Anne Carson’s “The Gender of Sound” and slowly presenting a broader argument of the erasure of women’s experiences. How do you feel about this today?

AB: Since 2015, big and small presses have been publishing a lot of important books that insist on various crucial truths of women’s experiences. I’m not sure how many more than in previous years, but it does feel like a shift. Maybe publishers are starting to trust that there’s an eager audience for books that contain these truths. I’m sure #MeToo has played a role in this.

I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing and being “in conversation with” some of these authors, like Maya Dusenbery, whose Doing Harm is a comprehensive exposé of medical sexism that backs up statistics with patient testimonials, Caren Beilin, whose Blackfishing the IUD takes the conversation about the serious ongoing side effects of the copper IUD outside of online message boards, Amy Long, whose Codependence is a formally inventive work of nonfiction from the too-often overlooked perspective of a chronic pain patient who needs opioids to live, and Jeannie Vanasco, whose Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was a Girl is a stunning memoir about sexual assault and friendship that destroys the myth of the stranger rapist. And then Porochista Khakpour’s Sick, Esmé Weijun Wang’s The Collected Schizophrenias, and Sonya Huber’s Pain Woman Takes Your Keys immediately come to mind. I haven’t yet read Karen Havelin’s Please Read This Leaflet Carefully or Chanel Miller’s Know My Name because there are so many good and important books about illness and rape to read; I look forward to these. Am I fully outing myself as a double Scorpio by saying I feel inspired by how much others are writing about these “intense,” “difficult” subjects that also obsess me? But seriously, it feels really good to see Tender Points in a stack with these other books. I like being part of a chorus of voices. I’m feeling less and less alone.

SK: In the first page of the book, you quote Diane di Prima’s “I have just realized that the stakes are myself.” This, to me, set the tone for the entire work. We start the book by immediately feeling that the stakes are so high, as high as oneself. Did you feel that the stakes were that high when you started working on this in 2013?

AB: Yes, absolutely. When I came across that sentence I realized how perfectly it captured how I felt about the project. Writing this book was an investigation into two traumas that have shaped my life and the connections between them. As my awareness of these traumas grew—as I developed symptoms of chronic pain, as I recalled memories of abuse—I grew more and more curious. It was my origin story, basically. I’m thinking of Jessica Jones breaking into IGH to find her medical records. I wanted to understand how these traumas had shaped my life.

And then as it turned out, the stakes wound up being higher than myself. I didn’t realize that so many other people had experiences like mine. But I’ve received emails from people who have chronic pain related to trauma saying that my book was the first time they’d seen their experience reflected back to them. That means a lot to me.

SK: The structure of Tender Points is an interesting one, alternating between lyrical, factual, personal, philosophical, excerpts from online forums and reports, and much more. Is this meant to evoke the discrepancies inherent to living with an “invisible” illness?

AB: That’s not something I thought about, but I do think it’s interesting to look at my book’s somewhat chaotic polyvocality next to the staid and limited information offered by western biomedicine. I’m thinking of the National Institutes of Health website saying “the causes of fibromyalgia are unknown, but there are probably a number of factors involved.” When the “answers” offered by institutions are so limited and unhelpful, why not invite a chorus of voices in? Doctors could learn a lot from looking at fibromyalgia message boards, from looking at books like mine and Caren’s and Maya’s and so on.

SK: I’m always interested in having conversations about skepticism and why women are often not believed. Your book exhibits painfully but carefully how women with disabilities suffer not only from their disabilities but from the lack of validation—which is meant to deny that the pain is real and implies that the trauma is imagined. I think your work really illustrates how hard it is to be a woman and to be believed. How do you experience this discourse today, do you think it’s changing for the better, and are we talking about these subject matters enough?

AB: As I said, it makes me really happy to see more and more books by chronically ill and disabled women, but we’re still so far from women being believed. I just did an event with filmmaker Sini Anderson, who’s working on an incredible and frankly urgent documentary called So Sick. It’s about late-stage Lyme disease, which primarily affects women and—in part because of that—is hugely under-researched and not taken seriously by many doctors.

We need art like this to move the culture along, to move medicine along with it. Left to themselves, I doubt doctors are going to start doing more late-stage Lyme disease research, I doubt doctors are going to start listening to their chronic pain patients. So films like Sini’s are crucial, books like Amy Long’s are crucial.

SK: As I understand, you’re currently working on your second book. Can you tell us a little bit more about it, and where can we follow your future endeavors?

AB: Yes! I’m working on a novel about the resilience of friendship under the strain of rape culture. I’m really interested in the less obvious, more complicated ways we fuck up around rape—the ways even the most well-meaning and thoughtful among us can hurt survivors without meaning to. And how so much of what motivates these harmful responses is our own histories of trauma. The narrator has fibromyalgia, because I didn’t want to miss an opportunity to bring a beautifully well-rounded character with fibromyalgia into the world. I’m not sure when it’ll be done, but my website is a good place to keep up with my various efforts and events.

Order Tender Points here!

Amy Berkowitz is the author of Tender Points. Other writing has appeared in publications including Bitch, McSweeney’s, and Wolfman New Life Quarterly. She’s the host of the Amy’s Kitchen Organics reading series, the coordinator of the Alley Cat Books writing residency, and the founder of Mondo Bummer, an experimental small press. She lives in a rent-controlled apartment in San Francisco, where she’s working on her second book.