Aditi Machado’s Emporium is a delectable journey through a modern “silk route” fraught with the consequences of capitalism and globalization, where she unravels and re-entangles the threads of commerce, language, and history in these cinematic, transitory sites of transaction, discovery and expression. Mallika Singh tunes into the contours of Emporium’s sensescape on a molecular level, wonders about the architecture of the text’s emporium, and inquires into the historical and archival research and literary influences that informed Machado’s process. Read on to hear about how somatic attention and ritual, dreams of labyrinthine produce markets, silk erotomania, porosity, and the memories of Machado’s home emporiums helped birth such a luscious, marvelous text.

— Santiago Valencia, Nightboat fellow

Aditi (left) in the silk blouse worn during writing. Mallika (right) holding Emporium.

Mallika: When I think of an emporium, I think first of perfume, I think of scent. The book is so full of sound and texture, but in one of my favorite poems, “Epistle to the Efficience,” the focus comes to smell. The poem lists not only particular aromas—green tea, rendered fat, sweet peach, cyanide—but also descriptions of the nature of scent, how it spreads and moves, how it is molecular and beyond grasp. In a book that critiques capitalism and globalization, I am curious about the molecular, invisible levels of exchange and transaction. Can you speak to the excessiveness and pleasure of scent / sense for the speaker and reader?

Aditi: Thanks for starting us off with sensation, Mallika. That’s where I like to begin too, in writing and in thought. In fact, I’d say that much before the poems in Emporium came to articulate anything like critique or refusal, they were simply poems of pleasure, focused on feeling, on somatic response. One of my favorite filmmakers is Bruno Dumont; his work is often called neo-Bressonian, philosophical—and it is, but only because he begins with (to quote him in translation) “sensation, not sense.” He renders the thickness of experience on film via a saturation of sight and sound. Early on in the writing of these poems, I was obsessed with two things: the textures of silk; and recurring dreams of shopping in produce markets. Those are the primary sites of—as you put it, molecular—exchange. (Your use of the word “molecular” has reminded me of one day looking up the science of smell: apparently, when you smell a rose (or a corpse), molecules of the rose (or the corpse) enter your body …) From there on I sometimes get to a place of criticism, or commentary, or maybe just “talking back.”

M: The emporium is a place and a not-place. We don’t know exactly where, or when, the merchant woman moving through this book is, and we hear multiple languages in the nondescript bustle and hum of a global marketplace. What was it like to architect the emporium? Did the place(s) you were in while writing and are in now influence you?

A: Broadly, for me, there’s a sense in which the merchant woman moves from east to west across the globe, but I didn’t map anything to real-world geography. Rather, each scenario occurs in a sort of in-between place (as trading posts or air hubs might be), with crowds of people and multiple languages being spoken.

Even so, certain places/architectures did shape the poems: any produce market I’ve ever been to (from the sabzi mandis of Bangalore to standard-issue US supermarkets); certain unusually labyrinthine farmers’ markets from my dreams (I wish these truly existed, because here you can buy any fruit or vegetable from any season or any part of the world and it’s still fresh and “local”); and the emporiums of my childhood and early adulthood. With respect to the latter: in India, you’re much more likely to find a shop, even a humble-looking one, called an emporium, especially if it sells fabric or local handicrafts. When I’ve had the pleasure of talking to fellow Indians about Emporium, it’s been exciting to discover that we have the same social and spatial reference for “emporium.” A couple such shops from my home city of Bangalore informed the sense of space, color, and material excess in the poems. I also drew on cinema and photographs (for example of Paris’ shopping arcades).

M: It feels like there is a depth of archival and historical research in this book. I was reminded of Saidiya Hartman’s practice of “critical fabulation,” which intertwines archival research and fictional narrative. I am currently living in New Mexico, observing the junipers drop their berries, and my attention was especially caught at the end of “Social Gesture.” You write, “And outside the poet cries, / look at juniper / and make gin / that’s my skill.” There is a magic that comes from playing with history and the archive—observing, imagining, and alchemizing it into poetry as juniper is transformed into liquor.

Can you speak to your research process? What is the significance of the report “Notes on the Passions of Patient M.” that sits at the center of the book? What did you discover that didn’t make its way in?

A: Oh, I did a lot of things that you could call research! Of the unsurprising kind: reading histories, searching databases, consulting encyclopedias. But as per usual, methods that privileged sensation over sense were the most fruitful. There was a somatic exercise in which I wore the same silk blouse every day for a week in order to generate language for the poems located in a silk emporium (gratitude to CAConrad and Douglas Kearney for this idea). I consulted etymologies, more for the sake of discovery than any belief in the “truth” of word histories. For example, learning that the echo of “porous” I hear in “emporium” comes from the Proto-Indo-European root -per (to lead, pass over) urged me to play with “pore/porosity,” and to think of the merchant woman as a porous subject. I think prosodic attention itself is research—the main research of writing. That, and translation. Translation is how “Notes on the Passions of Patient M” came to be.

still from The Cry of Silk

Several years ago, I was attempting to subtitle a film by Yvon Marciano called Le cri de la soie (The Cry of Silk). I made another attempt in late 2015/early 2016, but this time got distracted by the note at the end of the movie indicating that it’s a fictionalization of the life of Gaëtan Gatian de Clérambault, a pioneer psychiatrist most known for his classification of erotomania (a.k.a, de Clérambault’s syndrome). It turns out that in the early twentieth century he authored two reports on women exhibiting an autoerotic relationship to silk. (More explicitly: these women were arrested for stealing swatches of fabric, typically silk, from department stores—then still a novelty in the cities of Europe—for the purpose of sexual gratification.) This was a convoluted, heady kind of research that also led to much silliness. I translated a fair portion of those scientific reports, just for fun—later I decided to incorporate and parodize some of it into the text that became “Notes on the Passions of Patient M.” I guess it’s a kind of mysterious or rudderless text in the book, but for me an important one, because it deals with perversion, and/or is perverse, and/or pokes fun at the authority figure who decides what perversion is.

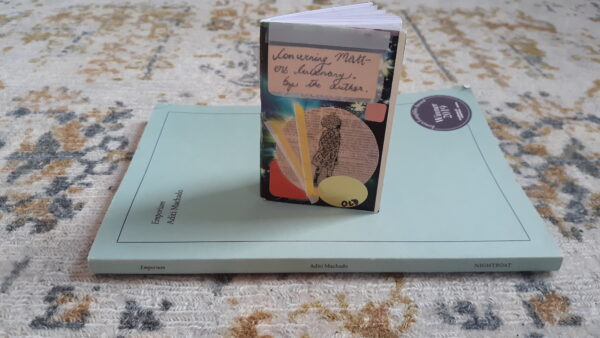

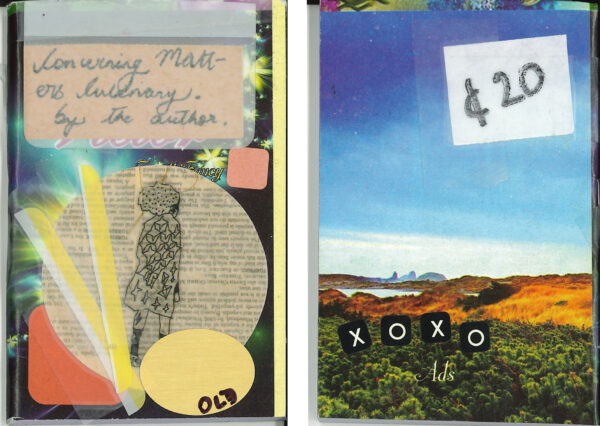

What didn’t make it in: there is a little recipe book the merchant woman finds in a flea market. The front and back covers appear as images on pages 30 and 31, but the recipes inside that “found object”/book-inside-the-book didn’t make it in. But they exist!

front & back covers of recipe book

M: The pursuit of and attention to sound seems central in this book. What was your sonic landscape while writing Emporium? What sounds surround you now?

A: While writing the poems, I would say my landscapes were quiet. India is a much noisier country than the US; in Denver and St. Louis, where I worked on these manuscripts, I lived in fairly quiet residential neighborhoods. Now I live near downtown Cincinnati where I can hear kids playing in the park, sirens, loud music, etc. In the summer and fall, late at night, I’d often hear this woman singing as she walked down my street. I’d fear for her safety, but maybe the song was creating a forcefield around her.

My sonic landscape is composed primarily of the books I read/my reading aloud from them.

M: The last lines of the book brought to mind In the Presence of Absence by Mahmoud Darwish. Emporium ends: “‘There is,’ I say, ‘inside you/an absence.’ ‘There is,’ I say, ‘inside you/a presence.’ I watch your interior grow.” Who are you in conversation with? Who do you learn from?

A: I’m moved that you thought of Mahmoud Darwish! There are too many people to mention. A few: Etel Adnan, Lisa Robertson, Don Mee Choi, Paul Celan, Fred Moten, Rosmarie Waldrop, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Gwendolyn Brooks, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Marcel Proust, all the translators I’ve ever read, students, teachers, Lewis Mumford’s The City in History, museums, lots and lots of movies…

Aditi Machado is a poet, translator, and essayist. Her second book of poems Emporium received the James Laughlin Award. Her other works include the poetry collection Some Beheadings (Nightboat, 2017), a translation from the French of Farid Tali’s Prosopopoeia (Action Books, 2016), and several chapbooks the most recent of which are a long poem called Rhapsody (Albion Books, 2020) and an essay titled The End (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020). A former Poetry Editor for Asymptote (2011-2019), she works as an Assistant Professor at the University of Cincinnati.

Mallika Singh is a poet, cook, and facilitator who writes about environment, surveillance, and intimacies. They are from many places and are currently frolicking in the high desert of New Mexico. Mallika is the author of the chapbook, Retrieval (Wendy’s Subway), and is pursuing a Certificate in Community Herbalism from the People’s Medicine School.