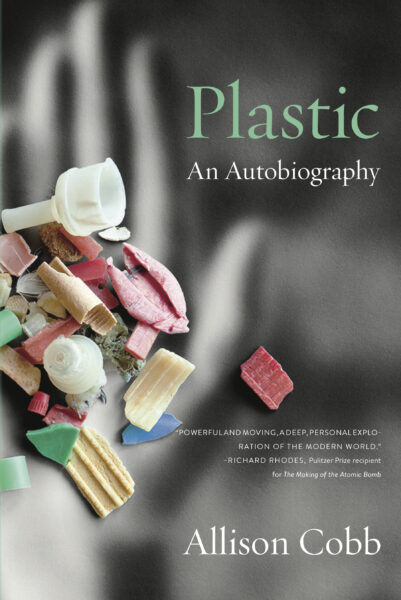

In celebration of the recent publication of Allison Cobb’s Plastic: An Autobiography, we asked Allison a few questions about the thinking and process behind the making of this expansive and ambitious book, which was ten years in the making.

***

What led you to writing Plastic?

We live at a time when our smallest daily actions (turning on a light, starting a car) have planetary impacts. It’s a difficult concept to grasp because climate change so exceeds the scale and scope of the human. Plastic, on the other hand, is concrete. Many of us have an intimate, daily relationship with it. But plastic takes so many shapes and qualities, and is so ubiquitous, we never really see it. It’s everywhere, but invisible. I thought if I could experience plastic as present and visible, I could maybe give some sense and shape to these vast planetary shifts that we all are implicated in and affected by, even if we can’t gather that evidence with our senses and so can’t really imagine our situation.

Plastic is a work which is both deeply researched and deeply felt. It opens with a quote from Karen Barad which states, “Knowing does not come from standing at a distance and representing but rather from a direct material engagement with the world.” Can you speak more about your “direct material engagement” with plastic through the process of writing this book?

I wanted to experience for myself, and for others, the material reality of plastic from its production to its disposal—a reality usually obscured behind the shiny objects that arrive at the front door or on a store shelf. I wanted to get a sense of this reality by understanding it intellectually and also by embodying it physically and emotionally. I used different tactics to achieve this. I brought a large plastic car part I found in the front yard into my house and have kept it with me for ten years—ultimately traveling across the country to try and return it to the Honda Odyssey factory. I spent years, off and on, collecting and recording all the plastic I found on my daily dog walk. I traveled to Kamilo Point in Hawai’i where plastic waste washes up from the ocean in enormous quantities. I met and formed relationships with communities on the Gulf Coast living with pollution from plastic plants. The trajectory of the book and my life are the same. We are entangled, the same way that people are entangled with the rain of plastic microparticles across the planet, plastic that we regularly eat and breathe. We cannot escape our entanglement with this technology, so it is important to make that entanglement visible. Then we can ask questions about how to change it.

You work as a writer for the Environmental Defense Fund. How did your day job affect the writing of the book?

I have spent twenty years in the environmental field and every day I process a deluge of information about planetary trauma and emergency. It grinds on my body, mind, and spirit. Writing books is the way I chart my own survival. My writing comes from desire—a desire to know, to understand, to be amazed, and maybe just to weep and mourn. I love what the scholar Eve Tuck has to say about desire-centered inquiries. Tuck is Unangax, an enrolled member of the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island, Alaska. She writes:

…desire is not mere wanting but our informed seeking. Desire is both the part of us that hankers for the desired and at the same time the part that learns to desire. It is closely tied to, or may even be, our wisdom.

As I’ve grown older, I’ve come to understand that joy—that staying connected, looking clear-eyed at our situation and maintaining compassion and connection, with self, with other—is much wiser, and harder, than despair.

You grew up in Los Alamos, and your dad was a physicist. What kind of effect did that have on your upbringing, and eventually on Plastic?

I came out of Los Alamos with a weighty sense of history, a history of violence tied to my own biography. My poetry teachers, Carolyn Forché and Susan Tichy, encouraged in me a serious engagement with that history through my writing. I was so fortunate to study with them and to learn global traditions of poetry as witness and resistance.

This book weaves together several narratives, from a baby albatross to a Navy pilot to your own personal history and stories. How did you meld the many different narratives into the story of Plastic?

I knew that I wanted to find as many threads of connection between my life and plastic as I could. I envisioned making this web of connections visible in the writing, to make real for myself and maybe for others the implications of the human imprint on this planet. I knew I wanted the threads to seem disparate and for the book to reveal their interconnections as it progressed—like, how can all these really different things be connected? From that basis my inquiry progressed intuitively and often by chance.

I first became intrigued by plastic after reading a piece in the Los Angeles Times in 2006 about a piece of plastic from WWII found inside a dead albatross chick. I decided to do a bit of investigating. I discovered the plastic likely came from a Navy squadron whose pilot was born and raised in Oregon, in a farming town not far from me. So, there was a connection. I also by chance came across a reference to plastic, an early form of polyethylene, used in the thermonuclear bomb. That was another connection. Those two discoveries cemented my obsession and propelled the book.

In addition to weaving together many disparate narratives, Plastic is also a formally varied work which moves between historical vignettes, to poetry, to more personal, diaristic forms. Can you talk about the experience of writing from these multiple approaches, and your decision to use form in this way?

I like to juxtapose different forms of writing because each reveals or brings forth a different facet of a complex reality. I feel freedom to do this because I am a poet and creative writer, not a scientist, journalist or historian, though I use the techniques of all of these disciplines. Our technocratic institutions reward the specialization of knowledge. That may be important for technological advancement. But humans are complex beings and can deeply understand the world only in its complexity. Wisdom rests in this kind of holistic knowing.

Juxtaposing different writing forms also helps to show how each is constructed, with its own set of rules and conventions. If one is reading a history book, one can become immersed in the world of its scholarship and see its claims to authority as total. I want to always remember to question those claims. A historical essay, followed by a poem on the same topic, followed by a personal narrative invites the reader to consider how the knowledge in the book has been produced. That knowledge is always multiple—built on the knowledge of others—and also, paradoxically, limited to a single self at its moment of composition. Exposing these as constructed moments includes the reader in the process of making meaning so that knowledge continues to grow as a collective, entangled effort. Anyway, that’s my hope.

What do you think is the most important thing that readers take away from the book?

That every manufactured object we touch contains the blood and breath and life of another being in it, or many beings. What does it mean to consume and discard such things on a mass scale? Globalization, technology, instant gratification internet shopping and delivery: all of this brings things close (objects, images, texts) and distances or obscures living beings. This is by design. Manufacturers and retailers prefer consumers not to know the details of how the computer you type on arrived in its pristine white box. If the true cost remains hidden corporations don’t have to pay it. Our survival as a species depends on our knowing. I think really embodying this knowledge would make our current way of life in wealthy countries impossible. And that is exactly the point. What we do with that knowledge? Well, that’s what happens next. It’s a huge question, full of possibilities for how we incarnate the future.

photo credit: Studio XIII Photography

Allison Cobb is the author of Plastic: An Autobiography. Her previous books include After We All Died, Born2, and Green-Wood.

Cobb’s work has appeared in Best American Poetry, Denver Quarterly, Colorado Review, and many other journals. She was a finalist for the Oregon Book Award and National Poetry Series; has been a resident artist at Djerassi and Playa; and received fellowships from the Oregon Arts Commission, the Regional Arts and Culture Council, and the New York Foundation for the Arts.

Cobb works for the Environmental Defense Fund and lives in Portland, Oregon.