The Making of SPEECH: Reflections on Abu Dhabi, Walking, Weaving, and Poetry

By Jill Magi

I live in a high rise building in Abu Dhabi called Sama Tower; sama means “sky” or “heavens” in Arabic. From my writing desk I look down on parking lots and streets and alleys where I see people making their way on the diagonal, diverting from the grid as they go. There is another important diagonal shape in this city: mosques that face Mecca. While the main avenues run parallel to the Gulf, each block houses at least one mosque that cuts through the city’s grid. This is a quintessential Abu Dhabi shape: the secular and the sacred, innovation and tradition alongside each other.

When we arrived over six years ago, I would sit at my writing desk and look down at the city below, entertaining the idea that I probably would not be a poet in Abu Dhabi. This felt important and somewhat troubling—so I wrote an essay entitled “Poetry in an Elsewhere.” I had arrived in a place where it seemed impossible for socialities to slip—I felt lockstep white, expat, temporary. I felt others and myself at a distance. All of this added up to the impossibility, I thought, of poetry.

When I walk in Abu Dhabi toward the grocery store, or over to the water’s edge, I pass through microclimates of languages—Urdu, Hindi, Arabic, Tagalog, sometimes German. And if I’m in a hotel or at the beach or on the walking path by the water, I sometimes hear Russian, more German, British English, sometimes American English. Nearly all these languages are happening in low volume. In New York City, the city where I became a poet, I think that people talk in public in order to contribute to the material of what can be overheard. Speech: an atmosphere and we all walk through, contributing. In Abu Dhabi, the low volume and the sea of languages made me wonder what my material would be and how I would record the cadences that create this place.

But as I worked on that essay, something else happened: I created a new document labeled “SPEECH.” Months passed and the document grew. I remember emerging from my studio in a daze and announcing, one evening, “I think I just wrote a book.” SPEECH is set in lines that mimic the pace of walking and the repeated movement of a weaver’s shuttle. The composite voice, in an attempt to make place, explores ideological middles: between citizen and migrant, history and the present, here and there, freedom and constraint, speaking and silence.

Michel de Certeau’s essay “Walking in the City” describes how the pedestrian defies the urban planner’s grid. The walker determines their own pace, direction; they stop and start at will. If the grid is about modernity’s efficiency—being able to move everyone and everything along uninterrupted site-lines—then the walker disrupts that purpose and legibility. Street-level life is a kind of diagonal text, according to de Certeau, where pedestrians’ paths are like “unrecognized poems in which each body is an element signed by many others.”

I share the view with many others that modernity is a disaster characterized by gross inequalities and highly organized, efficient plunder. The planet is imperiled. Trying out all textures of insurgency is what we must do regardless of whether or not we think it will save us. So I take De Certeau’s claims seriously. It’s not simply a stroll he’s talking about—he’s talking about insistent and creative paths of resistance. Art is a training in this way to walk and live: making and remaking the diagonal. In this remaking of space is a texture of pleasure—a sense of time that takes its time.

For the last several years I have been researching textiles—their practices, forms, traditions, and textile’s relationship to text. An Emirati textile tradition referenced often here in visual design—it is a kind of semiotics and stand-in for heritage and identity—is Bedouin-rooted weaving called “al sadu.” The word “sadu” actually refers to the length of a camel’s stride and this kind of cloth is woven on ground looms that stretch out into the desert, not confined by the dimensions of a house. And so this Bedouin-rooted weaving is a measure of pace and place.

I began to notice the parallels between this traditional woven cloth and pan-Arab modern architecture in Abu Dhabi. I was learning Abu Dhabi’s particular patterns, and its own rhetoric of walking. Because of the city plan, walking in Abu Dhabi means stepping off a curb where there is no cross walk, no set path. I yield, I am yielded to as I walk—all an improvisation. This rhetoric of walking might be called “textilic”—where human and non-human join in each other’s flows in unpredictable ways. The textilic, in opposition to the “hylomorphic” which privileges the blueprint, the design, the pre-set path. Here I’m building on Tim Ingold’s propositions in his essay “The textility of making” where he contrasts the textilic with the hylomorphic—the latter having been detrimentally overvalued in modernity.

Textile historian and theorist Victoria Mitchell writes on the importance of the use of thread in the early acts of measuring and building—that the first creation of measure was between a spinner’s body and a length of thread pulled out from a spindle, turning unstructured wool—called a roving—into string for knitting and weaving. And at the 2016 Kochi Biennale I watched Padmini Chettur’s dance/video work, “Varnam,” featuring women who sit in chairs and pull long invisible threads across their bodies and into the space around them. This diagonal marking of space seemed utterly feminine to me—a striking gesture that complicates the separateness and surety of before and after, in front of and behind, the cardinal directions, individual body and environment.

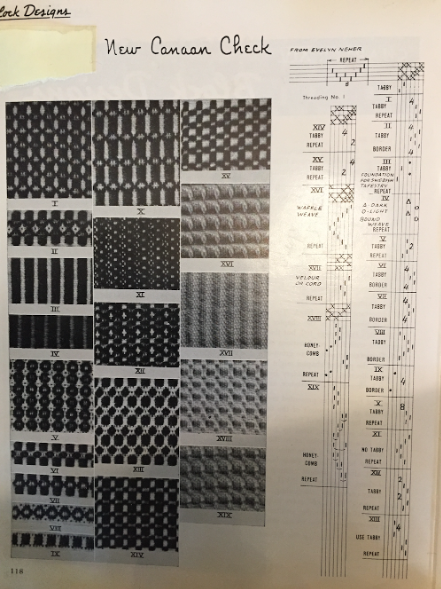

When I took my first weaving class in 2016 at the Marshfield School of Weaving in Vermont, I wanted to weave words into cloth. I came to weaving as a writer, missing, to some extent, the way that textile work is writing without words. Marshfield teaches its students on 18th century barn looms brought back into life after being found in New England sheds, barns, and basements. They don’t teach on draw looms or jacquard looms that make the patterning of words possible, so my first weaves were fairly complicated geometric works based on a collection of 19th century Pennsylvania weavers’ patterns. I was attracted to the intricacy of the code and thought this is what I needed to learn.

One year later, I went back to weaving school and worked on a bigger loom. I made a warp split down the middle into two colors. I alternated weft colors, so I ended up with bold blocks of color: a long and repeating grid. In one of the works I added an occasional indigo thread float weave—randomly placed and drifting lines of blue like free-verse in a field of striations and right-angle intersections.

But it wasn’t until the third summer that I learned what weaving really had to teach. I worked on an even wider loom and made a plain weave from off-white cotton warp and weft. The warp was really long and day after day, I wove and wove. It was a simple weave and I only had to pay attention to throwing the shuttle and advancing the cloth as I went.

After four days I cut the ends of the warp threads free and unrolled a continuous length—a scroll of papery beige cloth. So much potential! I held it in my arms knowing I wanted to do and make this, again and again.

As my fluency in weaving grew, the patterns became simple. And so weaving taught me how to write SPEECH: a text borne of repetition, walking, of setting out without the goal of an arrival at a sure space of knowing.

I now know that Abu Dhabi never needed me to decipher its shapes as if there is one way to read or one way to re-write its codes. A new texture—and a new book—has come from shirking the idea that there is a necessary text that I must write. Weaving and walking in Abu Dhabi has shown me to keep returning to the street and to the desk: ground and sky, living and walking, sure only of the motion that moves bodies and language back and forth along paths that intersect and diverge.

(Parts of this essay were first presented at The City College Center for Worker Education in fall of 2018 as part of their guest speaker series on “The City.” I am grateful to John Calagione for the invitation and opportunity to think through some of these ideas.)

Order your copy of SPEECH here!

Jill Magi works in text, image, and textile and her books include Threads, Torchwood, SLOT, Cadastral Map, LABOR, SIGN CLIMACTERIC, and a monograph on text-image entitled Pageviews/Innervisions (Rattapallax/Moving Furniture Press). Recent work has appeared in Best American Experimental Writing 2018, Boston Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Pheobe, and Rivulet. In October of 2017 Jill blogged for the Poetry Foundation, and in the spring of 2015 Jill wrote weekly commentaries for Jacket2 on “a textile poetics.” Her essays have appeared in The Edinburgh University Press Critical Medical Humanities Reader, The Force of What’s Possible: Accessibility and the Avant-garde, The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race in the Life of the Mind, and The Eco-Language Reader. Jill has been awarded residencies with the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Workspace program, the Brooklyn Textile Arts Center, and has had solo shows with Tashkeel in Dubai and the Project Space Gallery at New York University Abu Dhabi. For her community-based publishing work, Poets & Writers magazine named her as among the most inspiring writers in the world in 2010. Jill teaches in the literature/creative writing and visual arts programs at NYU Abu Dhabi where she joined the faculty in 2013.