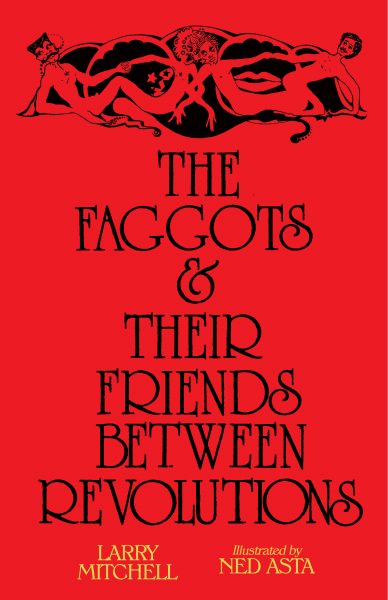

In 1977, the radical sounds of a commune near Ithaca, NY resounded from within a little red book: “…there are two important things to remember about the coming revolutions. The first is that we will get our asses kicked. The second is that we will win.” The zealous words of Larry Mitchell hovered there above hands knotted in solidarity and celebration, an illustration by fellow Lavender Hill Commune member Ned Asta. The two collaborated to create what would become one of the most seminal queer texts in small press, The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions. This quietly infamous and tender fable follows fairies, queens, faggots, faggatinas, women who love women, and dykalets as they move and love and cry and get their asses kicked and survive in the ashen landscape that is Ramrod, a city reeling from the myopic, destructive tendencies of “the men.”

We’re so excited, tickled really, to be reissuing this brilliant, flamboyant, and ever-poignant book with a new preface by Tourmaline and a new introduction by Morgan Bassichis. To kick off Pride month with a celebratory riotousness, I spoke with Morgan Bassichis about The Faggots and Their Friends, the faggotry of Lavender Hill and their friends, and what they’ve been up to between revolutions.

-June Shanahan

June Shanahan: For a much of its life, “The Faggots…” has been a marginal, underground queer text, having circulated within radical faerie communities and the like, originally printed by Larry Mitchell’s own Calamus Press, before passing through several little iterations, from pdfs to pamphlets, and most recently landing on Contagion Press’ roster. That history has allowed for this really cool mythology to envelop the work, and I’m curious about how you first came by it, or how it came by you, in light of its unconventional life? In your introduction for this new edition, you mention a friend named Bobby lent you a copy at one point, do you remember where he first discovered it?

Morgan Bassichis: Yes this book has had and continues to have such a vibrant and persistent life—it has gotten around! My roommate Bobby Cortez, an incredible quilt maker and person, gave me a copy when I was 20 years old living in his apartment on Haight and Ashbury in San Francisco. His boyfriend Blake Riley, a brilliant printer and creator of Tap Root Editions, stumbled on it he thinks at the wonderful and sadly now defunct Aardvark Bookstore on Church Street near Market. It felt so magical to receive this precious thing, not knowing anything about its history, like some family’s spellbook. I’ve had the strange sensation over the 15 years since that while I’ve read the book countless times, new pages keep appearing, like it won’t be finished. I still have that feeling. I’ve met so many people who have stories like mine, who were given a copy or a scan from a friend who said “you have to read this.” Such a sweet queer mode of transmission, the passing of books among friends.

JS: In the Fall of 2017 you devised and performed a musical adaptation of the book at the New Museum. Can you talk a little about the process of that adaption? The lanky and eccentric illustrations of Ned Asta are somewhat indelible to the story and I wonder if/how you might have interpreted them through movement and sound?

MB: It was a very collaborative and organic process, prompted by an invitation from Johanna Burton and Sara O’Keeffe at the New Museum to make something for their 40th anniversary show, and completely made possible by their wise and fierce support from start to finish. It started with the painter TM Davy and I improvising music based on pages from the book, in his apartment in Brooklyn and then on Fire Island. He has a magical way of thinking about chords as colors, so he would say “This song feels orange or blue,” and start playing, I would find a melody and hone in on specific phrases from the text, and he would jump in and harmonize. A number of songs emerged, and then the brilliant performers Michi Osato, Una Osato, and Don Christian Jones joined us and we started playing, improvising, dreaming. The artist Anna Betbeze designed this gorgeous and cozy psychedelic living room set. Many friends helped throughout, particularly the wonderful dramaturg and performer Sacha Yanow. We spent a lot of time with the book itself, reading it to one another, and that became the organizing principle of the performance—inviting the audience to read, weaving in songs, skits, jokes. Before the shows, we went up to meet the Lavender Hill members in Ithaca, and felt this deep resonance with them, their spirit of care for one another, irreverence, sexual and gender liberation. That also informed the performance. We wanted it to feel like your friends invited you over and put on a little show for you in the living room.

JS: Throughout the book there are these aphoristic breaks, one of which reads, “FAGGOT WISDOM: Romantic love, the last distraction, keeps us alive until the revolutions come.” Elsewhere, it’s noted that, while “the faggots consider it a sacred pleasure to engage in indiscriminate promiscuous sexuality… Horniness makes the faggots uneasy and nasty and distracts them from the revolutions.” What’s your take on the illusory romantic and homo distractibility? Are the events of queer love not little revolutions in and of themselves?

MB: I love these, like, platitudes! “This is how it is!” How bold? And I love that they can even contradict one another, performing certainty and ambivalence at the same time, back and forth, folding in on itself. It is perhaps a kind of satire of leftist dogma or absolutism, while still managing to be polemical. “Distraction” is admonished and then celebrated within the course of a few pages. I like to think of the book and even the commune not as claiming to be “right” or “cogent” (which they certainly never did) but dreaming big and simultaneously not taking itself very seriously., Larry and this circle of friends had an enduring critique of gay marriage, the normativity of the couple form, and assimilation—the “romance” that “romantic love” refers to—which I know is very important to many in my generation as well. They really wanted something else, they wanted everything! This was informed by their commitment to feminism (which has long had a critique of marriage) and gay liberation, and their interest in finding intimacy, commitment, sex, and love everywhere, not just where we are told we should look for it. And of course the characters in the book just like all of us find love and connection wherever we can find it–we get caught in the very things that might be “distracting” us, and thank god we do. We fall short of our platitudes, but we find bits and pieces of freedom there, too, wherever we are.

JS: There’s a narrative thread of faggot activity and pastime being that of reenactment of the past, a storytelling with the body engaged by the characters in these fables, queens, faggots, and fairies alike. The faggots “cultivate the most obscure and outrageous parts of the past…so these parts of the past are never lost,” and people gather in the streets to watch “dykalets” and “faggatinas” reenact sagas of brave queers-past on the piles of rubble. Obviously this book carries forth the legacy of the Lavender Hill commune, but what kind of legacies less tangible do you think this book also embodies? When people freshly pick up The Faggots, what do you imagine happens in an historical sense?

MB: I love the idea of people seeing different legacies of resistance resonating here. I think the prose, which is sort of mythical, makes itself available for multiple interpretations. Certainly there are direct references to the Stonewall uprising in the text, but I think as you say, there is a recognition of a continuity of struggle throughout human history, to contest the forces of capitalism, white supremacy, and hetero-patriarcy that try to portray themselves as inevitable and irrefutable. The terms of rebellion, disruption, sabotage, retreat, clandestinity, mutual aid, the ways in which empire and resistance ebb and flow—that they are not static—certainly feel deeply relevant today.

JS: I understand you spent a considerable amount of time with the notebooks and photos of Larry Mitchell that are held at Cornell. What was your experience like going through those archives and what were some of the more distinctive pieces of vestige you were able to find from Mitchell and the Lavender Hill commune? Naming characters like “Warren-And-His-Fuckpole” in a town called “Ramrod,” Mitchell must have been a deeply funny and sharp human, as well as deeply emotional. In going through those records of his, did that impression come through?

MB: I am really grateful to Brenda Marston, Curator of the Human Sexuality Collection at Cornell, who has done so much work to archive radical queer sexual histories, including Mitchell’s archives. Thank goddess for the radical archivists, and radicals who archive their own lives!! What a gift they are leaving for future generations, a cure for the amnesia and forgetting that our world painfully does to radical histories. We need to know radical histories and ways of being, imperfect as they are, because they give us courage and humility and because they are on our team, they want to help us! I remember Angela Davis talking in a speech years ago about how the state has a long institutional memory—it’s job is to track and undermine radical movements, after all—so we better do some remembering ourselves. OK, this was not the question you asked. To answer your question, I was most moved by all the written communication in the archives. Postcards, letters. Logistical, banal, emotional, political. Utilities are due, when should I come visit, I miss you, we broke up, etc. but because they had to sit down and either handwrite these notes or write them on a typewriter, there is a level of presence that is palpable. Here’s what I’m feeling and seeing as I write this to you, here’s how the weather and the political climate and my health are acting on me. All of the envelopes would be dressed up with stickers, drawings, photo booth photos, their names turned into affectionate diminutives. A densely layered history of friendships made partially legible through written communication. It was very moving.

JS: Though Larry Mitchell has since passed, Ned Asta still lives in the area of the original commune in Upstate New York and, in addition to your archival spelunking, you’ve also spent some time up there with her, no? What kinds of projects, communally and artistically, has she been involved with since The Faggots and how might we engage with them?

MB: Ned Asta is a force of nature, she is truly a one of a kind person, although I think that she is secretly twins with Una Osato, one of the artists who co-created the performance and the Lavender Hill Historical Society that we made at the Brooklyn Museum. They both have a seemingly endless number of boxes of photos and papers under their beds—the space under their beds is like a clown car—and have a commitment to pleasure like no other. Ned got the nickname “Loose Tomato” because she loved tube tops, but I think it’s also because she’s singing her own song. At 72, Ned still works at Moosewood Restaurant—where most of the Lavender Hill members have worked or still do as cooks, servers, collective members, or cookbook authors—and is often making hand-drawn flyers for staff parties, preparing feasts for holidays and dying her hair to match, creating beautiful bouquets from her garden for the tables at Moosewood, swimming in her pond, spending time with her wonderful son Tazio. She also co-founded the Ithaca Breast Cancer Alliance with Andi Gladstone in 1994. She has been so welcoming to all of us wanting to hang out with her, and so generous to lend her original artwork, hundreds of photos, and memorabilia for our installation at the Brooklyn Museum. In our first conversation she said “I’m a proud bisexual so if that’s going to be a problem for you, tell me now.” She’s the coolest.

Preorder your copy of The Faggots now!

MORGAN BASSICHIS is a comedic performer whose shows have been described as “out there” (by Morgan’s mother) and “super intense” (by Morgan). Recent performances include Klezmer for Beginners at Abrons Arts Center (2019), Damned If You Duet at the Kitchen (2018), More Protest Songs! at Danspace Project (2018), and The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions: The Musical at the New Museum (2017). Morgan has presented work at the Hirshhorn Museum, MoMA PS1, the Portland Institute of Contemporary Art, and the Whitney Museum, and has received support from Art Matters, Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Morgan lives in New York City, and has contributed writing to Artforum, Radical History Review, Captive Genders, and other anthologies.