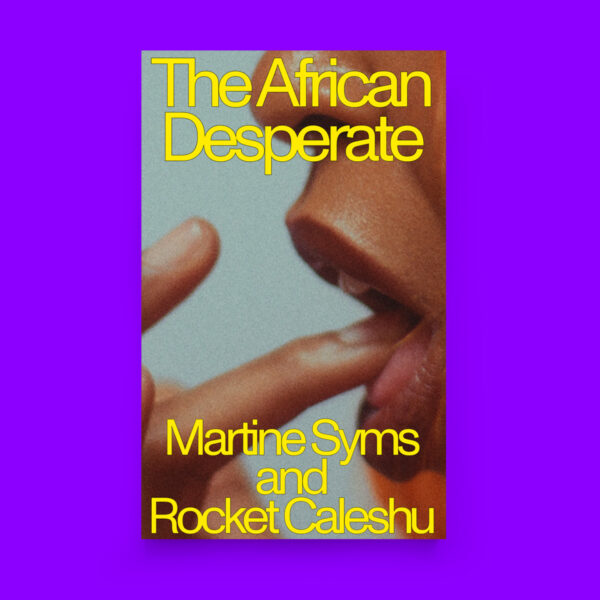

Rosie Stockton interviews Martine Syms & Rocket Caleshu, co-authors of The African Desperate!

To celebrate the recent publication of The African Desperate, fellow Nightboat author Rosie Stockton (Permanent Volta) speaks to Martine Syms and Rocket Caleshu about their process collaborating, the differences between the screenplay and the film, the art world, and more. Take a look below!

____________________

Rosie Stockton: First of all, congratulations on writing and producing an incredible movie, in addition to the publication of the screenplay as a stunning book. Can you talk about the decision to publish the screenplay – particularly with a queer poetry press!–and speak to what it holds as a text object that might differ from the film object?

Martine Syms: Thank you! It’s a sexy little book. I answered these questions back to front because this question seems hard to answer today. Every time I went to the bookstore I came back with at least one Nightboat book, and I started to follow and seek em out. During the Creative Capital retreat, I asked to speak with Stephen Motika. I’ve been publishing since 2007 first under Golden Age and then from 2012 as Dominica Publishing. Actually earlier if you count my teen fanzine ANGER THERMOMETER. I’ve always been fascinated by the places that books can go. I’m always surprised to find out who has a zine I made 15 years ago. It’s a format I’m very loyal to because it’s connected me with many people. It’s about making ideas public and making publics around those ideas.

Rocket Caleshu: Thanks Rosie! It’s been a real thrill to get to work with Nightboat, who consistently and decisively put out exactly what everyone wants and needs to read. Martine brought up the idea of publishing the screenplay as a book, and we both knew right away we wanted to work with Nightboat. Martine has a way of making ideas move in all kinds of uncanny ways, through all kinds of forms. The text can certainly be read as a collaborative queer poem– we were generating a poetics as we wrote it. It never felt confined exclusively within the genre of screenplay, or that that was a limiting factor. I hope that the pace and materiality of the text allows it to unfold into a different experience than that of watching the film.

Rosie: I am interested in your collaborative writing process–both how the mechanics of the collaborative writing process looked, and the engagement with your backgrounds as an artist and a poet.

Martine: Rocket and I spent a lot of 2020 writing another screenplay. We’ve also made 5-10 video pieces and commercials over the past few years. We have a collaboration built on a shared interest in the TRUTH (hahaha), an evil sense of humor, and being ruled by Venus.

Rocket: It’s true, we both love unadulterated, gnarly TRUTH. And pleasure. The mechanics were whatever we needed them to be. Drafting back and forth, and then getting into the granularity of it at a big table in a very Upstate barn.

Rosie: I just so happened to read The African Desperate before seeing the movie, which lets us into the texture of the writer’s voice behind the scenes, before actors bring their own interpretations, fantasies, attitudes, and delivery to the lines. Reading it as a poet, rather than an actor, I thought a lot about how directives remain suspended in the reader’s fantasy. I am interested in the relation between poetry on the page and how you worked to translate (or what failed to translate) to the screen.

Martine: This script is the broadest vision of the film. Once in production the text goes through many breakdowns from each department head. How many outfit changes are there, what props need to be available when, and a million other questions. I always think of this moment on set when our script supervisor was asking where the robots were to my confusion. Huh? Then she read the line, “Twin cyborgs…” and I was like “Oh, we were just having fun with language!”

Rocket: Thank you for reading it as a poet <3. The suspension in fantasy is a fun interlude in the filmmaking process, before everyone gets their paws on it and you start to see how the gap between fantasy and production will be bridged.

Rosie: One of my favorite things about the book is the peak into the voice of the stage directions, which become a sort of hilarious and irreverent character of their own. At times they read like the Palace’s inner monologue, and at other times they read as an entirely other atmospheric character, as if the walls themselves are speaking. Do you conceive of the stage directions as a character? How did you think about this tone?

Martine: I prefer when the screen direction gives you a sense of what it’s like to watch the film. If there is a reveal how can I put that into the reading experience? The film shifts between different point-of-views: Palace’s perspective, an “objective/neutral” frame, and then a shifting subject who’s watching Palace. We follow a similar pattern in the script but mostly to orient the reader as to what they should pay attention to at any given moment. Rocket and I have worked together for several years and enjoy making each other laugh. That’s always a motivator when you’re passing a text back and forth. What can I slip in here that will get a crack outta my buddy!?

Rocket: The stage directions are in part a space to convey the moods, humors, and specificities of the world we were creating. There was no neutrality mandate, no need to make a story that could fit in any number of settings. This story is Art School 2017, and maybe it should send a shiver down your spine. We were free to be as sardonic or earnest as we needed to be to get the ~multilayered temperment~ of the story and its characters across.

Rosie: The African Desperate opens with Palace, a black woman, subjected to a crit by a panel of all-white professors, who respond with varying levels of apathy, aggressiveness, racism and meaningless jargon. The book and film are in part about the absurdly incongruous ways Black Studies, art, and theory is taken up (or not) by art school culture. The status of the visual, representation, and staging of the “scene” are debated in many of the texts (Hartman, Moten, Wynter) that are referenced in the book and film. With this in mind, how did you grapple with the question of the visual or the “scene” from the process of writing to the process of making the film?

Martine: We were always making a film and cannonballing into the problems of representation. I wanted that scene to touch all of the ideas that would unfold over the course of the film. The larger issues of the art world play out in the interpersonal of art school. We had fun writing it and using the mode of critique to address the film and the viewer directly. Hartman, Moten, Wynter, and Thomas are guiding lights into some of our theoretical framing, but I don’t think you need to have read them to participate. Though if you have, there are easter eggs!

Rocket: The film starts with an ending, so the opening salvo had to hold the unbridled institutional insanity the protagonist had been faced with for the duration of the program. This is the context, and I think it translates no matter what industry you’ve found yourself toiling in.

Rosie: A screenplay is always just a blueprint for what a film might become: what is captured on a camera is rarely exactly what is written on the page itself. I am interested in your approach to improvisation both in writing the screenplay, and what kind of improvisation you invited during the production of the film.

Martine: The script provided us with a clear plan and a narrative structure. I worked closely with our DP Daisy Zhou to figure out the scenes, and our production designer Lauren Anderson to set the stage. The beauty of being writer-director / writer-producer is that we could rewrite if a scene wasn’t working. I wanted to be responsive to our incredible actors, but there wasn’t much improvisation on set. The car scene was the most difficult to get right, we rewrote it twice, but in the end Diamond and Aaron’s performances came out of the moment.

Rocket: We were able to rewrite scenes to respond to the needs of the production, but improvisation was limited. Martine drew gorgeous performances out of the actors. I was surprised by how moving the slippage between text and film was for me– one an object of a process about to take place, the other bearing the mark of time, and what transpired within the portal of its own making.

Rosie Stockton is a poet based in Los Angeles. Their first book, Permanent Volta, is the recipient of the 2019 Sawtooth Prize, and was published by Nightboat Books in 2021. Their poems have been published by Publication Studio, VOLT, Jubilat, Apogee, Mask Magazine, and WONDER. They are currently a Ph.D. Student in Gender Studies at UCLA.

Writer and Director Martine Syms has earned wide recognition for a practice that combines conceptual grit, humor, and social commentary. She has shown extensively, including solo exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and Tate Liverpool. She has also done commissioned work for brands such as Prada, Nike, Celine, Kanye West, and NTS Radio, among others. She is a recipient of the Creative Capital Award, a United States Artists fellowship, the Tiffany Foundation award, and the Future Fields Art Prize.

Writer Rocket Caleshu is based in Los Angeles. He holds a BA in Africana Studies from Brown University and an MFA in Creative Writing/Critical Studies from the California Institute of the Arts, where he was the inaugural Truman Capote Literary Fellow. He received the 2016 Black Warrior Review Prize in Nonfiction. His work has been published in Poetry Magazine, New Delta Review, Dilettante Journal, and others. He is working on a book of essays titled Whatever, and a book about love co-written with a clown.