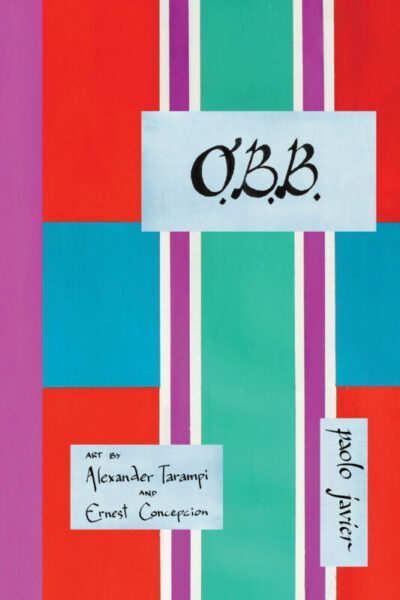

Today we’re celebrating the publication of O.B.B. by Paolo Javier, featuring artwork by Ernest Concepcion and Alexander Tarampi! O.B.B. aka The Original Brown Boy is comprised of a series of comic book collaborations with text and image, as well as poems and essays that expand upon the nature of comics themselves. O.B.B. has many layered and intersecting identities: postcolonial, manifesto, conceptual, collaborative, avant garde, political cartoon, and more. In celebration of the book’s release, we’re excited to share a list of comics titles that inspired the creation of O.B.B., written by author Paolo Javier. Read on below!

(We have attempted to keep the formatting of the images as consistent as possible, but our website has formatting limitations–please keep this in mind!)

November 2, 2021, marks the official publication date of O.B.B., a weird postcolonial techno dreampop comics poem that’s taken me two decades to realize. In a zoom visit to a college class two weeks ago, the professor requested that I provide a list of comics titles that informed my thought and creation of O.B.B. What follows here is not intended to be definitive by any means.

1. Carousel, spring 2006 issue + Chain # 8: Comics

I came across Canadian cartoonist Seth (nee Gregory Gallant)’s interview in Carousel’s spring 2006 issue, where he offers the following provocation to Marc Ngui: “I have felt, for some time, a connection between comics and poetry. It’s an obvious connection to anyone who has ever sat down and tried to write a comic strip” (17). Apparently, “the idea first occurred to [Seth]. . . in the late 80’s when [he] was studying Charles Schulz’s Peanuts strips” and found his “four-panel setup. . .just like reading a haiku; it had a specific rhythm to how he set up the panels and the dialogue. Three beats: doot doot doot—followed by an infinitesimal pause, and then the final beat: doot.” There is a “sameness of rhythm” between haikus and the strips, while “the haikus mostly [end] with a nature reference separated off in the final line.”

As well, reading and teaching Jena Osman and Juliana Spahr’s groundbreaking anthology of comics poetry—still the best one out there IMHO—, in my nascent college course offerings on the two art forms back in the aughts provided an indispensable guide for my initial experiments.

2. The Mimeo Revolution

Baffling Means by Clark Coolidge + Philip Guston

Joe Brainard’s collaborations with poets

I moved to NYC on my own in the fall of ’99, inspired by the interdisciplinary poetry of the second generation of New York School Poets and the Poetry Project community. I continue to draw inspiration from the Mimeo Revolution, whose aesthetic O.B.B. wears on its sleeve across several of its chapters. As I note in O.B.B.’s afterword: “poets have known about and explored this relationship since the advent of the modern cartoon, often to virtuosic effect. O.B.B. is my own engagement with comics and the poem where I play with dialogic text and drawing, illustration, collage, photocopy, and painting—cues shamelessly taken from the hybrid comics, collages, founds, and poem-picture collaborations of my idols in the New York School, especially Joe Brainard, George Schneeman, but also Jess Collins’ collages.”

3. Independent and DIY comics

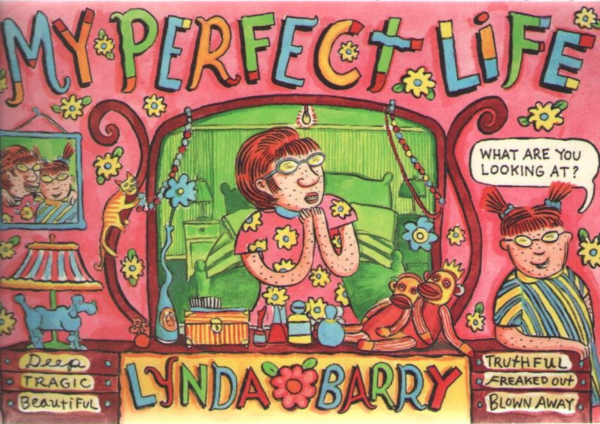

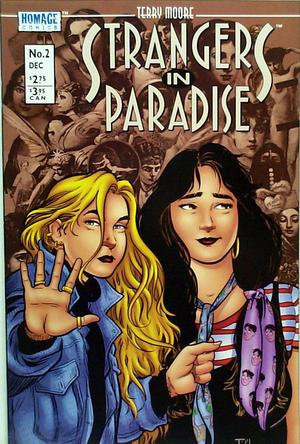

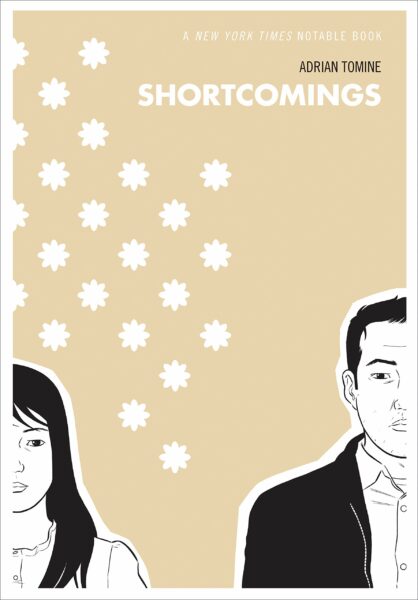

O.B.B.’s terms of creation—improvisation, anti-narrativity, no deadlines—flies in the face of industry norms. So I drew inspiration from the comics creators whose orchestrations are more attuned to the rhythms and disjunctions of a poem than a short story or novel to experiment with narrative in my own comics poem. Lynda Barry, Seichi Hayashi, Craig Thompson, Terry Moore, and Adrian Tomine are author/artists whose work I’ll take with me to my desert island. I cannot overstate how vital their work continues to remain for yours truly.

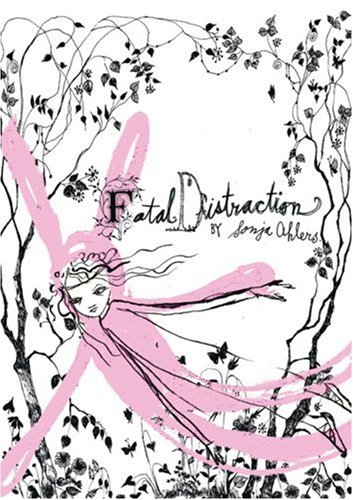

4. Fatal Distraction by Sonja Ahlers

A friend of mine who is also a novelist and comics nerd complimented me for the typeface and design of O.B.B. last week, to which I told them that I have my former department xerox machines to thank. Xerox artists of the 70s certainly inspired me, but I specifically turned to Vancouver’s own Sonja Ahlers for inspiration and guidance.

In O.B.B.‘s Afterword: “Sweetly recalling the work of Ray Johnson, Joe Brainard, Bern Porter, Robert Seydel, and Kathleen Hanna, Fatal Distraction is a break-up album–to use the European term for comics–made up of black & white images and poems/texts that are hand-drawn and written, typed and word processed, collaged, found, and cut-up. Ahlers orders her pages in a non-linear sequence, giving the impression of the book as “cobbled together”, a sort of comics poetry equivalent to The Book of Disquiet, Fernando Pessoa’s enduring experiment in accretive prose. Also, Fatal Distraction’s pages are both unnumbered and without chapter breaks, a further signal to the reader to assume a more active role, including “…shuffl{ing} and creat{ing} different narratives, of which there are seemingly endless possibilities here,” as Pop Matters reviewer Zachary Houle keenly observes.”

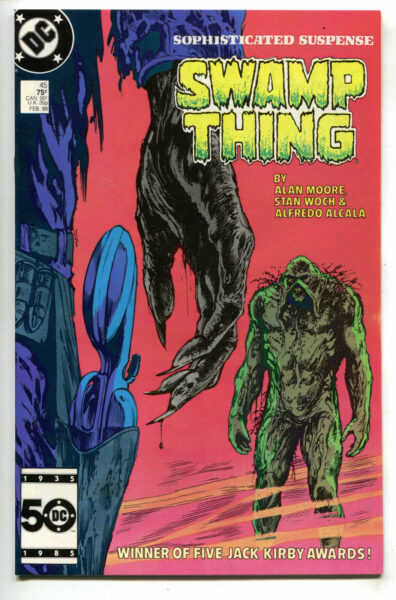

5. Magick, Hellspawn, & the Dreaming

When I resumed comics collecting in 2003, I went nuts over Mike Mignola’s Hellboy, and returned to Alan Moore’s Promethea and Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series, books that I absorbed as a high school student and college undergrad. Small wonder that these titles struck my fancy, given their narratives overt interest in poetry. As I note in my afterword to O.B.B.: “All three writers/artists revel in poetic allusion and de-center their narrators; they experiment with negative space, and interrupt straightforward action-to-action panel sequences with non-sequitur transitions, thereby inviting greater closure, to borrow Scott McCloud’s term, from the reader. The visuals of these comics teem with pagan and religious symbols that look and read like illuminated versions of diaries by Austin Osman Spare, H.D., and Aleister Crowley.” All three books also embrace the monster as the protagonist, and collapse horror, the superhero genre, and the weird tale. O.B.B. follows in a similar spirit, merging and mixing up the genres of autofiction, sci fi, and the political cartoon, along with copious nods to the weird and to apocalyptic narratives.

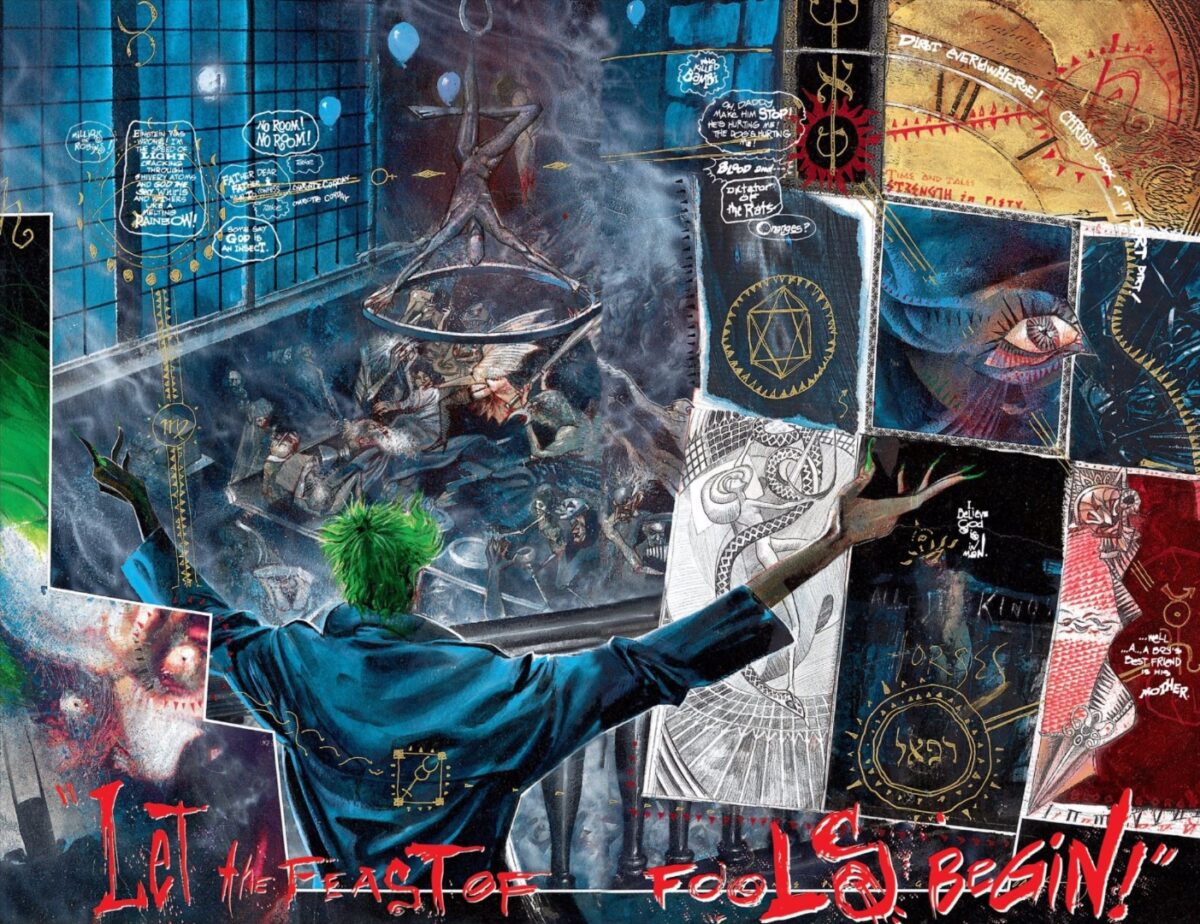

6. Grant Morrison & Rimbaud’s derangement of the senses

From O.B.B.’s Afterword: “Grant Morrison became a superstar as a result of their work writing the D.C./Vertigo books Doom Patrol, Arkham Asylum, and The Invisibles, comics deeply influenced by their abiding interest in the poetry and praxis of the Romantics, French Symbolists, Dada, Surrealism, Futurism, and the Beats.”

At the time of their run on Doom Patrol, Morrison had already developed a following with their 1989 collaboration with British artist Dave McKean on the original Batman tale Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, which sold an improbable 500,000 copies, making it the most successful graphic novel of its time. Most remarkable about this mainstream book is its hermeticism, inspired by “surrealism, Eastern European creepiness, Cocteau, Artaud, Svankmajer, the Brothers Quay, etc.” Morrison “wanted to approach Batman from the point of view of the dreamlike, emotional and irrational hemisphere, as a response to the very literal, “realistic” “left brain” treatment of superheroes which was in vogue at the time…” (Morrison, Arkham Asylum, notes to script). The book’s subtitle is taken from a Philip Larkin poem, but ghosts of European outsider poets, artists, and writers such as Rimbaud, de Sade, Breton, Jung, Ernst, Cahune, Kahlo, Colquhoun, Crowley, and Bacon haunt its conception and design.

Dave McKean’s illustrations collapse drawing, collage, photography, and painting, filling the pages with symbols that point to ancient and modern occult, pagan, and religious sources. Constantly alluding to literary, artistic, and philosophical characters and authors, Arkham Asylum aspires to read like the grandchild of The Waste Land and Pisan Cantos. (Not coincidentally, the character of Amadeus Arkham, founder of the infamous asylum for Batman’s villains, resembles Ezra Pound).”

Re-reading Morrison and McKean’s collaboration in Arkham Asylum gave me so much permission to operate with dream logic and magick while drafting and summoning the texts and the sequence of O.B.B.

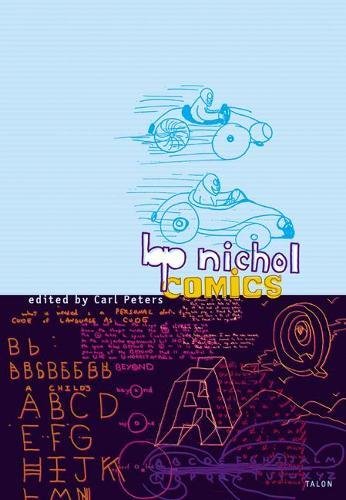

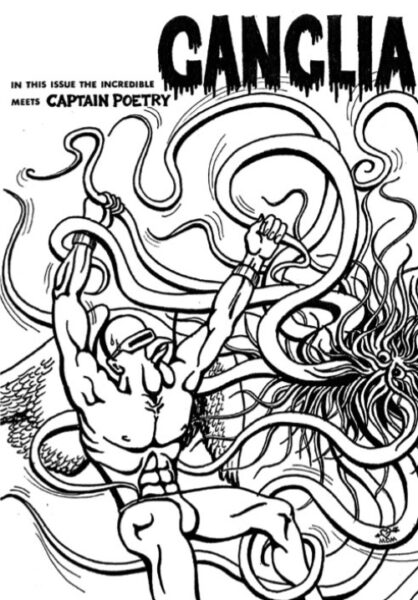

7. bpNichol Comics

Also from the Afterword: “Vancouver-born bp Nichol was a poet, first and foremost, and his work anticipated many of my own formal interrogations in O.B.B.: if we are tp break free of the TYPE oriented trap then we must break thru into the non-linear languages—here we use language in the broad sense of VESSEL container & carrier of messages both emotional & intellectual—SEMIOTIC POETRY is intriguing but depends on LINEAR keys—the COMIC STRIP offers a FUSION of linear & NON-linear elements…” (Nichol, bpnc).

…. Nichol remains for me THE poet to explore the connections between our art and comics with singular devotion and persistence.”

Simply put: there would be no completing O.B.B. without the example of bpNichol’s devotion to comics poetry, in addition to his boundlessly inventive explorations in/of both language art forms.

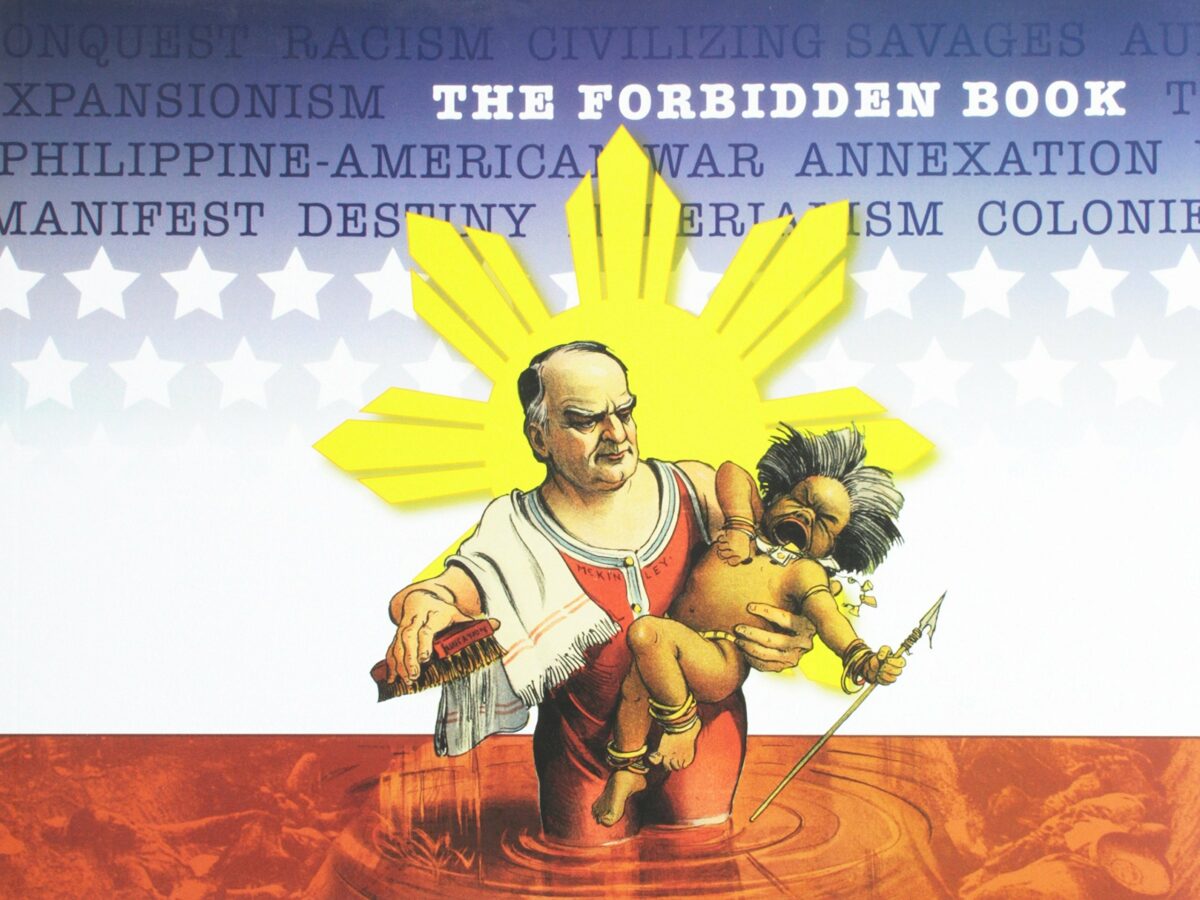

8. The Forbidden Book

From O.B.B.’s Afterword: “While visiting the Bay Area in support of my new book of poems, I was introduced by the visual artist Mel Vera Cruz to Abe Ignacio, Enrique de la Cruz, Jorge Emmanuel, and Helen Toribio’s The Forbidden Book: The Philippine-American War in Political Cartoons, a soul-shaking history of American imperialism in the PI—a colony purchased from Spain for $20 million U.S. —lensed through the profoundly racist and jingoistic political cartoons appearing in various prominent American newspapers and magazines such as LIFE and Harper’s Weekly between 1898 to 1903. Without question, The Forbidden Book inspires the meta-panel structure for O.B.B., and emboldens the turns of my comics poem’s (weird postcolonial techno dreampop shoe)gaze at FilAm history, trans/nationalism, migration, desire, identity, melancholia, and shame.”

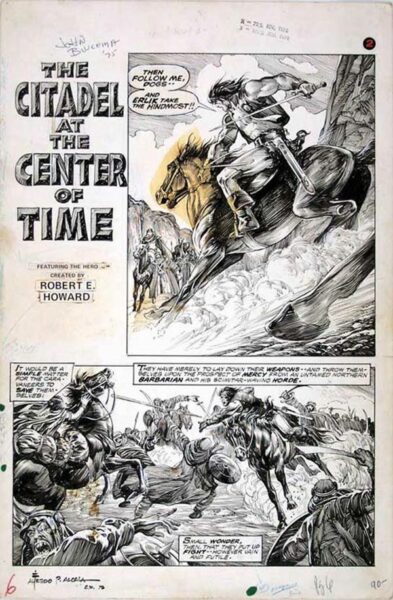

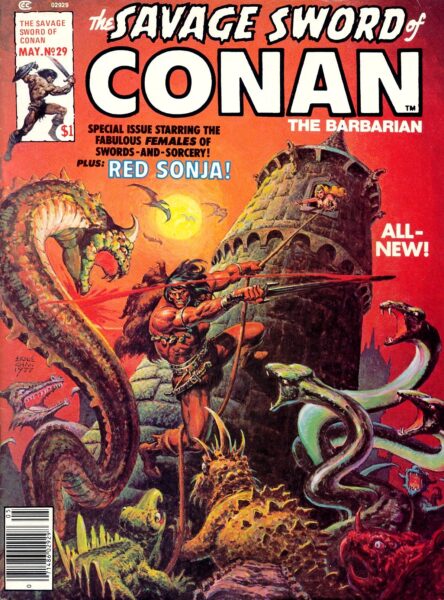

9. The “Filipino Invasion”

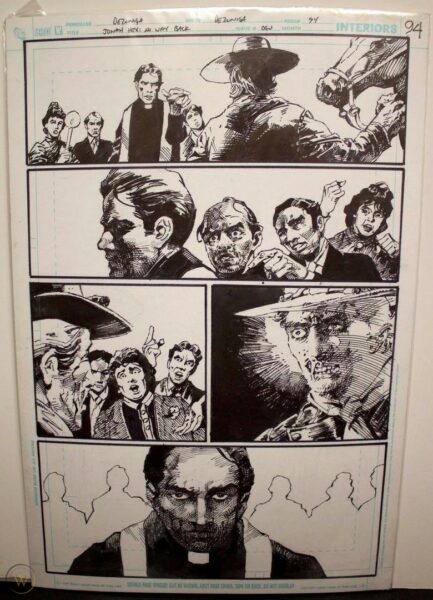

O.B.B.’s foray into sci-fi and monstrosity in chapter 4 (“Last Gasp”) is my homage to Tony de Zuñiga, Nestor Redondo, Alex Niño, Alfredo Alcala, Francisco Coching, Ernie Chan, & the pioneering group of komikeros from the Philippines illustrating mainstream U.S. American comics in the 70s & 80s. When I was eight or nine years old, my Chinese Filipino neighbors handed down to me a couple of boxes full of DC’s anthologies of horror and weird tales, along with Marvel’s sword & sorcery magazines, which prominently featured these legendary manongs.

In hindsight, what’s fascinating is how oblivious I was to the fact that these Bronze Age comics I adored and cherished were also co-authored and illustrated by my own kababayan. Only after I picked up issue #4 of the Comic Book Artist at Midtown Comics in 2004 did I finally make this connection—and realize the deep ties of my own exploration of comics & poetry to an expanding view of U.S. American and international comics history.