Judy Grahn, author of Eruptions of Inanna, talks about queer and trans figures in ancient mythology

Happy Birthday Judy Grahn! To celebrate, Eruptions of Inanna author Judy Grahn discusses the relationships between ancient tablets and small presses, queer and trans figures in Sumerian mythology, mythic realism and how the lamentation form fits into today’s society with Nightboat intern Ryan Cook.

____________________________________________________

Ryan: I wanted to start off by saying Happy Birthday! How are you going to spend it?

Judy: Thanks Ryan! When I turned eighty a couple of years ago the plan was a big public party; Covid-19 put a stop to that idea. So instead I invited our little family “pod”–remember those?–for halibut cooked three different ways. And root beer floats. This year I expect I will put on one of my beautiful new snap button cowboy shirts. My spouse and I will drive over to the coast to have lunch at Duarte’s Tavern, which features great bread, cream of artichoke soup, and fried oysters.

Ryan: I am so excited to be interviewing and celebrating you today. I also share an interest and passion for Inanna—particularly writing about the queer and trans aspects to the myths. I’d love to invite you to talk a little bit about the nonbinary and trans representation that crops up in Sumerian mythology, as it’s the reason I first got so interested in this work as well. The Kurgarra and the Galaturra, as well as the Pilipili were all talked about in your book Eruptions of Inanna as androgynous shamanistic temple personnel that would dance, sing, chant, and recite charms. The Sumerian descent myth talks about how Kurgarra and Galaturra were brought into this world when Enki flicked some dirt from underneath his fingernail. What was it like to see ancient examples of gender subversiveness celebrated, and how do you think that the qualities of genderqueer themes of ancient Sumer apply to today’s world?

Judy: As I said in the chapter comparing the Book of Job with the poetry of Enheduanna, the high priestess of Ur–the fundamentals of Job’s story and poetry were first laid down in her much earlier poetry. As transliterated by Betty De Shong Meador as well as the University of Oxford Sumerian Text scholars, the priestess told a story of being most pious toward her deity, most helpful to her people, and then of suddenly losing everything–her temple, her position, her reputation, her health. Through her unyielding faith, including in her own righteousness, she regains everything. The two stories, Enheduanna’s and Job’s, parallel in fascinating and detailed ways. But the Job version has left out crucial elements pertinent to today’s world. Most importantly, the deity being female and immanent as the conscious life force coursing through all life forms, all of nature.

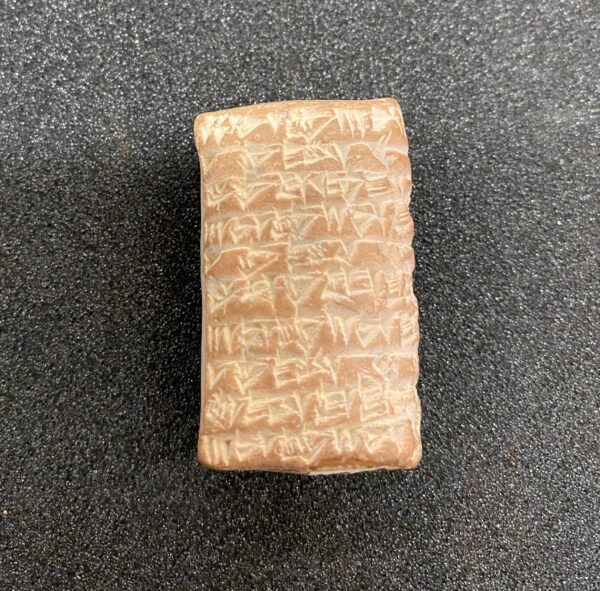

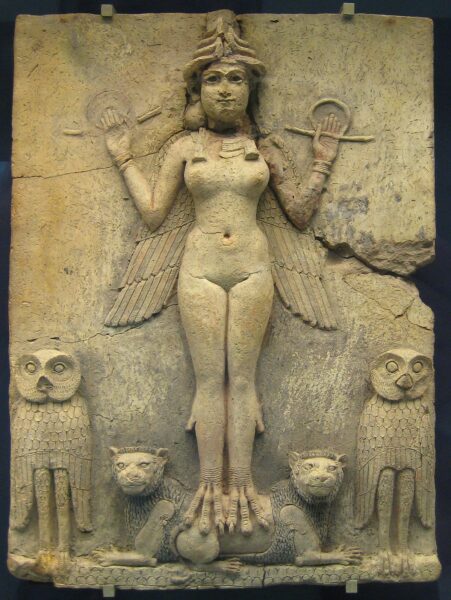

Ancient Sumerian Tablet

In the Sumerian version there is also no argument about sin as there is in the biblical version. And, to your point, no mention in Job of the pilipili or “head-overturned,” the transgendered people Inanna sweeps into her temple personnel.

Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld story relates, as you say, the god Enki creating two genderqueer or trans characters, the Kurgarra and the Galaturra, from dirt under his fingernails. They carry sacred water and sacred plant to bring Inanna back to life. It’s important to realize that “dirt” didn’t have negative connotations, that I can perceive. Enki is a master gardener, god of fertilizing water, and the word “Land” is consistently capitalized in the Oxford University’s translations, indicating the importance of fertile land to these city-dwelling farmers. The dirt under Enki’s nails was quite special.

The Sumerians and other early Mesopotamians recognized more than two genders. Will Roscoe, Gwendolyn Leick and others have shone light on this. According to one scholar, Kathleen McCaffrey, Sumerians understood two sexes at birth, the material bodies of male or female. They also held that people have an inner body essence that could lead to one of four other gender states in adulthood. Inanna in particular had capacity to change a person’s gender, whether they wished it or not.

I just want people who have been disappointed in religious or spiritual encounters, because they or their friends are left out, or demonized, or there’s a war against women, or the primary importance of the earth is diminished, to read and even teach the stories in Eruptions that bring into dramatic focus what has been missing.

Ryan: In the introduction to Eruptions of Inanna you discussed your long-standing collaboration with Betty De Shong Meador—specifically the time you were first introduced into Inanna’s exaltations through Betty. How do you feel that the research into those exaltations changed your writing’s prosody, style, and themes? Has the goddess found her way into other parts of your work?

Judy: Betty Meador came to work with me because I was already working with multiple goddess themes, and she had been told I was able to handle what the Jungian’s call “the dark”. By which I believe they mean the violent, the unconventionally sexual, and otherwise off the rails stuff. Starting in 1972, I had already written, publicly delivered, and published several works involving goddesses by 1985, so I had the creds to work with Betty. And, she did a spectacular job in her book Inanna: Lady of Largest Heart, presenting a view of female deity we had not seen before. I was hooked for life on Inanna–her sexual range, fascinating stories, personal presence, and ever-extending powers.

Ryan: In Hanging on Our Own Bones, you describe these poems as a Lamentation: “Lamentation in a song and poem, especially by women mourning death in public ways, has widespread history, from Africa to Eurasia, at least, if not over the globe.” I absolutely agree, and loved the Lamentation style from ancient Mesopotamian literature to the lament of Dido— but in a world so tethered to constant broadcasted tragedy, how did it feel to work within the lament style?

Judy: Lamentation, in my opinion, is for the purpose of more than feeling; it points also to change. Current news broadcasting is for instant sensations, emotions of fear, rage, momentary sympathy, very shallow, and driven by desire for hits and viewers, ratings, profits, and having very little or nothing to do with the social good. I don’t always succeed but I have tried to craft lamentation poetry that calls out social and personal problems while also suggesting some ways out. And I’m not done yet. By the way, Annie Lennox in 2020 produced a really moving version of Dido’s Lament.

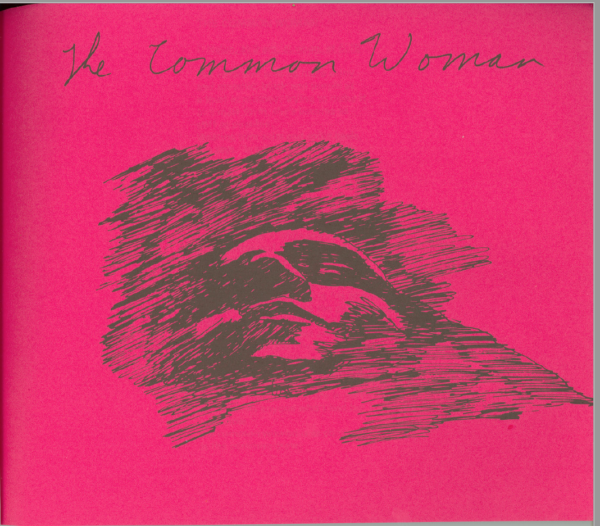

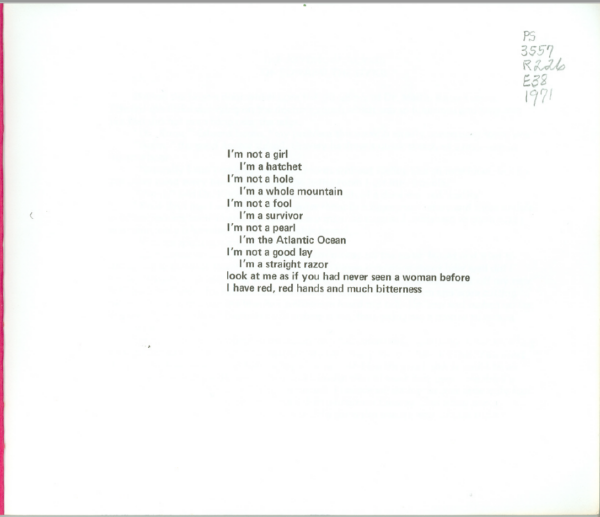

interior image from Edward the Dyke Zine, printed by the Woman’s Press Collective, 1971

Ryan: Part of what I found so wonderful about your extensive body of work is that so much of it exists in the zines, journals, and scans that show their history like the clay tablets that speak of Inanna. I know you probably weren’t using reeds and clay tablets, but similarly to the scribes of ancient Sumer who, when their styluses trembled, thanked the goddess of writing for inspiration, What sort of electrifying emotions did you feel when working with your hands? What kind of relationship does tangibility have within poetry?

Judy: I too tremble in the temple of creativity and go into ungrounded altered states. My habit of taking handwritten notes in notebooks located all over my habitats means I can take notes down at night or in a cafe or wherever. The physical notebooks become personal, like talking to a friend. Lots of writers do this. I also had the marvelous experience of co-founding a press with heavy printing and binding equipment. The act of producing books is so thrilling–learning the industry, the machines–hauling the paper around–boxing and shipping the finished volumes, seeing the books in people’s hands. The physical engagement is even more embodied than the ancient scribes pressing their wooden stylus tools into damp clay tablets or rolling seal rings into clay to make a reverse patternarly letter press! I recommend every poet make chapbooks for friends—retty little single poem booklets with fancy paper, to keep the spirit of free speech as well as personal expression.

interior image from Edward the Dyke Zine, printed by the Woman’s Press Collective, 1971

Ryan: So much of writing about mythology and the occult involves extensive research into the details of the often thousands of different translations/details for a myth. Because mythology was oral and therefore a lot of details changed from city to city—at the end of the day, how do you decide which version of the myth or detail you are going to tell?

Judy: This decision is all about your prejudices and desires at the time of writing. What points do you most want to make? In the Eruptions‘ chapter on the journey of Gilgamesh, I chose out of the many translations, the one by John Gardner and John Meier because of their very useful extensive notes, and also because they ended the myth at a place that I could use to argue the story’s relationship to secularism. The young king spurns everything about Inanna, the powerful goddess of his city, and sets off on his own seeking the afterlife, yet is unable to find his own way either to reincarnation or to paradise. He is left with putting a statue up in the public courtyard and his dead friend’s advice–have a lot of sons to carry on your memory. The brilliant myth gave me a chance to highlight the astonishing range of characteristics of Inanna, as well as describing the important turn toward patriarchy in prebiblical history.

Ryan: Do you have any tips for writers getting bogged down in the details for research over in poems involving myth?

Judy: I find the act of writing contemporary relevant poetry using mythology to be very challenging because the process so easily turns stiff and distant. I find the best recipe for flexibility to be what I call “mythic realism”: Use myth that attaches to you and leave plenty of room in the poem for real life details, that help readers (and you!) stay involved. So my verse play The Queen of Swords is based on the four thousand year old Descent Myth of Inanna, but I set it in a 1960s style underground Lesbian bar full of raucous dykes and a drag queen who all tell mouthy unwanted truths, using Gay jokes and plenty of other humor. The Sumerian myth frames the action; the characters are more contemporary. In contrast, in my long poem “A Woman Is Talking to Death,” the various mythic elements are just hinted in a poem that is set in modern urban life throughout. So, the “six white horses” of death’s carriage, or “six jolly cowboys to carry my coffin,” of the folk song “Streets of Laredo” turned into “six big policemen, all white, and dressed as they do…” in my poem.

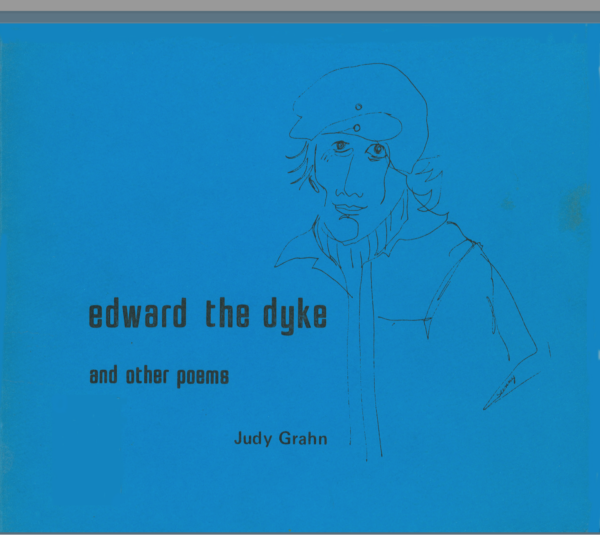

Cover from Edward the Dyke Zine, printed by the Woman’s Press Collective, 1971

Ryan: The Psychoanalysis of Edward the Dyke is a personal favorite poem of mine because of the satirical approach to gender in the eyes of psychoanalytic theory, how do you find the joy and humor in the confusing fields of your experience to the balance of queerness in relation to gender?

Judy: Satire, I find, can overwhelm through its own cleverness; sarcasm needs to be handled with care or it can obliterate your message. Humor opens the reader’s heart, enabling reception of difficult or new material. “The Psychoanalysis of Edward the Dyke” satirizes the psychiatric diagnoses of homosexuality as a mental illness, and one doctor’s “treatment” as futile conversion therapy. I wrote this after listening to the advice of Frank Kameny, leader of the D.C. Mattachine Society, of which I was a member in 1965-66. Confronting the psychiatric establishment became a tactic both for our Gay Women’s Liberation groups, as well as various Gay activists; my piece, which I distributed beginning in 1969, no doubt had some effect. The diagnosis was dropped after Frank Kameny and Barbara Gittings, in 1973, set up a professional discussion panel that included a Gay psychiatrist; the irony was too much. That change by the psychiatric establishment was a good step forward, and more steps followed; there is much more good work to do.

***

Judy Grahn is an internationally known poet, author, mythographer, and cultural theorist. Her works include seven books of nonfiction, two book-length poems, five poetry collections, a reader, and a novel. An early Gay activist who walked the first picket of the White House for Gay rights in 1965, she later founded Gay Women’s Liberation and the Women’s Press Collective. Her intention with writing is to replace obsolete philosophies with better ones. Her subjects range from LGBT history and mythology to feminist critiques of current crises, new origin theories of inclusion, what makes us human, taking racism personally in dismantling white supremacy, and stories of how to engage with creature-minds and spirit. Judy’s engagement with the rich literature of ancient Mesopotamia began in the 1980s, with two book-length poems, and now has blossomed into Eruptions of Inanna: Justice, Gender, and Erotic Power, a retelling of the adventures and wisdom of the great goddess of love, eroticism, justice, ecology, fortune, and gender relations. Judy holds a Ph.D. in Integral Studies/Women’s Spirituality, from the California Institute of Integral Studies. She researched her dissertation in South India and brings lived experience and knowledge of contemporary rituals to cast further light on the brilliant ancient poetry of the Sumerians.