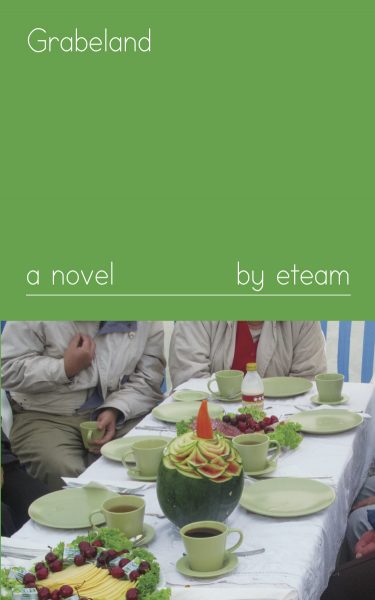

For a book whose title invokes a function (grabeland means “land for digging”), eteam’s art novel reads like a travelogue, touring the inner exiles of its characters as they test the limitations of their existence. The novel lives somewhere at the intersection of the Internet and land art, in a country that no longer exists, and a culture rooted in constraint. Through accumulation of personal and collective experiences, histories, and anecdotes, Grabeland opens the door for a speculative understanding of our relationship with the world and ourselves—at a time where globalization and the worldwide web allow us so much access. Here, Franziska Lamprecht and Hajoe Moderegger (the duo known as eteam) answer some questions about their project, its tenets, and what they think about the relationship between art and literature. Read on!

—Sahar Khraibani

Sahar Khraibani: As an artifact of performative intervention, a documentation (or perhaps a nod) to land art, and the perennial use of the Internet, Grabeland has been classified as an art novel. What are your own parameters for what defines an art novel, and how do you feel about this category? In what sense is Grabeland novelistic, and in what sense is it art?

eteam: We like the term “art novel” because it seems to be some sort of hybrid, something that exists in the space of a book and in a space where art takes place. In 2013 David Moroto and Joanna Zielinska organized a show called “The Book Lovers” at the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts in Manhattan. The show drew attention to the fact that visual artists have written novels throughout the 20th century, and they tried to figure out, through readings, performances, and talks, how to define the genre of the “art novel.” They showed artist novels in a glass case, and viewers could take them out and read them wearing white gloves. That was a pretty funny experience. Maybe that’s what an art novel is, you need to read it wearing white gloves?

David and Joanna continued the project and they have now an actual physical collection of over 500 titles, which is housed at M HKA, in Antwerp, Belgium and an online database. Back in 2013 we had been familiar with some of the books and artists they had categorized, Sophie Calle, Jill Magid, Bernadette Corporation, Keren Cytter, Andy Warhol, Christopher K.Ho, Kurt Schwitters, among others, but until that show, we had not thought about the “art novel” as a possible a category.

Categories are helpful tools in explaining to others what you are doing, but besides that, we don’t use them. To us everything is a “project:” performance, video, installation, traveling, eating, living, we don’t really separate.

SK: The book begins with you moving from the digital world to the real one, and the hardship of toggling between both worlds. But as we move forward in the narrative, we start to understand the repercussions of this movement. What are its implications?

eteam: Toggling between the digital and the real world—it’s probably like online dating. Over time you become more literate reading and interpreting the online data. You become less surprised when you see how online profiles manifest in real life. Instead of online dating we bought land on eBay. It’s probably easier for a couple to have a love affair with a piece of land than with another person or another couple. And the repercussions? They are very complex: excitement, enchantment, frustration, longing, despair, love, space.

SK: Much of the novel’s humor and pathos boils down to the peculiarities of the dynamic between you, the landlords of a foreign place, and the residents who’ve lived there their entire lives, as well as the suspicions, and the miscommunications—what do you make of this sample relationship in a larger context of our world today?

eteam: We are always told that “we need to understand” the others in order to respect them. But maybe that is only one side of the coin. Maybe we also have to learn and accept that we can “not understand,” and that this “not understanding” can be a beautiful thing, a more humble way of being. In Grabeland we practiced to sit out quite a bit of incomprehension and bewilderment and let those things find their own places. And once we allowed that to happen something came around, that was incredibly familiar. Something very relatable and close to our hearts. And that “coming around” was a huge relief—for all sides involved. It was such a huge relief that it usually caused laughter, or at least smiles. The happiness lasted only for a moment, but was worth sucking it up for that moment. These moments have a tendency to become precious memories.

SK: There’s a prevalent ethics of power throughout Grabeland—urban/rural, owner/tenant, narrator/character. However, by the very act of the fictionalization of yourselves and the “novelization” of your project, you attempt to confront these dynamics. What about these ethical tropes lingered after finishing the project?

eteam: What has been there all the time: “Power to the people,” and “power to the arts.” And the “novelization?” One of our favorite quotes of Ryan Trecartin’s video “Any Ever” is: “Am I overexisting or am I over existing? That’s my inside joke.” That is one of the most profound questions, and one of the most hilarious ones. It’s still such a good update of “to be or not to be” and how to possibly be today.

SK: How does the premise of Grabeland relate to ideas of cultural displacement and the nostalgic, yet very real, demise of smaller communities and villages? But also, how are cultural expanses measured in a time where globalization and the Internet allow us to access so much? Can you speak more to this aspect, or perhaps the influences that lead to these ideas, in your work?

eteam: Think about a ten-mile radius around the gardens in Dasdorf, and then think around a ten-mile radius around the Empire State Building. If people choose or are forced to live their life within spatially confined parameters in times of globalization, one can understand this limitation as an ignorant bubble. But one can also think of it as a stable focal point from where one can explore universes: ones that lie outside the tangible; and that can be reached and related to with imagination, telescopes, microscopes, math, art, thoughts.

Around 2005 Daniel Kehlmann’s Measuring the World became a huge hit. The novel compared the lives and works of Karl Friedrich Gauss, the German mathematician who “measured” the universe without ever leaving his hometown, and the German naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt who “measured” the world by traveling extensively through South-America. Between Humboldt’s and Gauss’ approaches stretches a spectrum of reaching, estimating, judging, scrutinizing the world that is endless, so we have to pick some small details to work with, one at a time.

To imagine that a small garden parcel in former East Germany contains the world…is that nostalgia? Distance, space—it all feels a bit irrelevant with the expansion of digital communication. Google Street View can bring us to places and we can virtually visit museums and stores if we feel inclined to do so. What fascinated us circling Dasdorf in a horse carriage together with our tenants for a week, was the fact that we found as many signs of globalization within a ten mile radius of Dasdorf as you can find pieces of plastic garbage on a 10ft beach stretch in Hawaii or discarded fast-food containers along a 10ft highway stretch in upstate NY.

SK: That’s such a good point, and brings me to my next thought/question. As I understand it, the writing of this novel was very much process-driven—the concept evolved from video installations and lent itself to a written novel. How would you describe your practice to a literary audience? Can we expect more literary work on the horizon?

eteam: Our practice is that of trying to understand and learn. Things that happened, things we did, things we are going to do, things that are impossible. How we come to this understanding (or not) takes many forms. Writing a novel was, in a way, an extension of the voiceovers we had written for our videos, but it had probably also as much to do with the fact that we live in NYC in a small, one room apartment with a child. Instead of an artist studio, we have one table on which our son does his homework, where we eat, fold laundry. It does not leave room for much else. We have space to sit on a chair and put a laptop on our lap, and we have access to amazing libraries in NYC. So we did this. We worked with what was there. Now we are building a studio in upstate NY. That might change everything. But who knows, we also became a bit addicted to that writing thing, it’s hard stopping it now.

SK: What projects are you currently working on? Anything exciting for us to look out for?

eteam: We hope we can return to Hong Kong next year and continue our work with Master Wong Fai and his troupe members. The learning curve to engage with traditional Chinese puppetry is incredibly steep, so we really like that challenge. We performed our last collaborative play “Zhong-Kui–and the Reform of Hell” several times in Hong Kong in very different venues and at some point we would like to perform it in the U.S. just to see how that would feel.

We are also finishing up a manuscript called Throwback. It’s a novella that tries to understand what happens when you spend too much time in places like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC. How is one’s world-view shaped by institutions like these?

Order your copy of Grabeland here!

eteam is a two people collaboration who uses video, performance and writing to articulate encounters at the edges of diverging cultural, technical and aesthetical universes. Tripping over earthly planes they trigger transactions between its occupants and establish wireless connections. Their narratives have screened internationally in video- and film festivals, they lectured in universities, presented in art galleries and museums and performed in the desert, on fields, in caves and on mountaintops, in ships, black box theaters and horse-drawn wagons. They could not have done this without the generous support of Creative Capital and The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, Art in General, NYSCA, NYFA, Rhizome, CLUI, Taipei Artist Village, Eyebeam, Smack Mellon, Yaddo and the MacDowell Colony, the City College of New York and the Hong Kong Baptist University, among many others.