An Interview With Jon L Pitt, Translator of Tree Spirits Grass Spirits

Hirmoi Ito is one of Japan’s most prominent contemporary writers, and has been since her debut, Kusaki no sora (translated into English as The Plants and the Sky). Her work has always shared an affinity with the plant world — in a previous interview, she’s stated that plants “teach us how to think differently about our own existences, our own belonging and our own mortality.” This collection — Tree Spirits Grass Spirits, out now from Nightboat — does just that.

Below is a conversation with her translator, Jon L Pitt, Assistant Professor of East Asian Studies at UC Irvine. We discuss the translation — an entangled practice in and of itself — and what we learn when we look at (and with) the more-than-human.

—Dante Silva

Dante Silva: I wanted to start with the title of this collection, translated from the original Kodama Kusadama. Jon, you state in the introduction that the word for “Tree Spirits”—“Kodama” in Japanese—can also mean echoes. Could you speak more about this word and its translations? Where do we see (or hear) the echoes of Kodama in the present?

Jon L Pitt: Readers might recognize the word if they’ve ever taken the shinkansen (bullet train) in Japan, one of which is named “Kodama.” But it’s an old word, one we can find in works of classical Japanese literature like Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji (11th century) and Yoshida Kenkō’s Essays in Idleness (14th century). In both cases, kodama refers to spirits that live in and among the trees. The well-known Studio Ghibli anime Princess Mononoke features characters called “kodama”—those small flickering spirits that live in the forests. Kodama are also considered a type of yōkai, those supernatural creatures that are found in Japanese folklore.

The entry for “kodama” from Toriyama Sekien’s Gazu hyakki yakō (18th century). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

But the word also appears in the early 17th century Nippo Jisho or Vocabulario da Lingoa de Iapam—a Japanese-Portuguese dictionary compiled by Jesuit missionaries—where it is defined as a “reverberation in the mountains.” It has that kind of sonorous quality to it, as well. I think Hiromi’s use of the word in the title plays on both meanings. On the one hand, the book thinks seriously about the vitality of trees and plant life in general. At the same time, it’s a work that feels as if it’s being read aloud, even if one reads it alone to themselves. I often get the feeling when I read Hiromi’s work that her voice resounds off the written page. I tried to capture as much of this as possible in the translation—the vitality and echoing sound of the words themselves.

It’s worth noting that while “kodama” is a regular word, one you can find in Japanese dictionaries, “kusadama” (“grass spirits”) is not. I think by placing “tree spirits” next to “grass spirits,” Hiromi is both evoking the classical meanings of the first word, but also asking her readers to think of the very idea of “tree spirits” in a new way—one that is on par with the idea of “grass spirits.” Trees have a long history of spiritual significance in Japan, but grasses—wildflowers, weeds, etc.—do not command the same kind of awe. I think Hiromi is challenging us to appreciate the vitality of the small plants as well. What kind of spirits live among the grasses at our feet? What kinds of reverberations happen down there?

Dante Silva: To pull from the introduction once more — you write that “at any given time, Ito may use one or more of the following names for a plant: 1) its Japanese common name, 2) its Japanese scientific name, 3) its Latin scientific name, or 4) its common English name.”

How did you translate the plants that appear in the collection? How do you carry the “everyday lives and emotions” (as Hiromi writes) that are embedded in colloquialisms?

Jon L Pitt: This was one of the more challenging aspects of translating this book. So much of what makes the work compelling in the original Japanese is the play between the different kinds of names plants might have. Hiromi uses these different names to different poetic ends. She writes about incanting scientific names as if they were sutras. She compares the different common names, puzzling at times over the differences between English and Japanese names for the same plant. Because names are so important to the collection, I realized I needed to take each plant on a case-by-case basis, and think hard about what type of name is being used in a given instance and why. As I write about in the preface to the translation, this approach resulted in a translation with a fair amount of transliterated Japanese words—plant names that I felt should remain in their original Japanese. There are places where I insert parentheticals with the English common name or the Latin scientific name, but sometimes it felt more true to the poetic spirit of the text to leave the word alone and not provide too much context.

A good example is unohana, which, as Hiromi explains, can mean “deutzia,” but what the chapter is really taking about is a much more vague sense of unohana, one that includes all kinds of small white flowers. Here, I felt the point was to follow along as Hiromi tries to find the name of a flower she caught a fleeting glimpse of, and to understand what the word unohana means. The whole chapter is a kind of definition, albeit one that ends in a kind of resigned but strangely content conclusion: “I was fine with this flower being “a certain” utsugi of the honeysuckle family. It wasn’t an unohana, but it was a variety of utsugi that bloomed in clumps, and I was fine with that.”

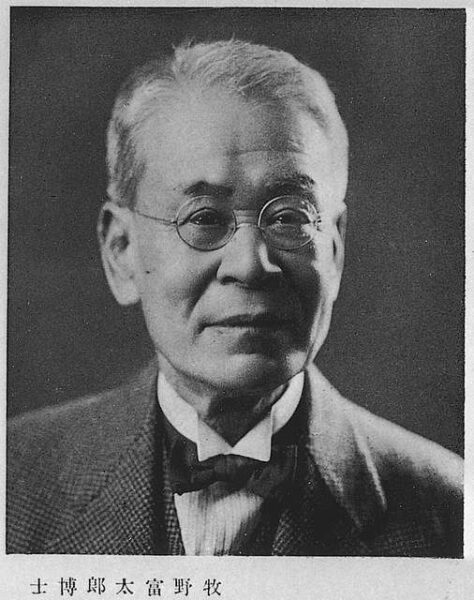

What makes that chapter interesting is that it is specifically not about “everyday lives and emotions,” but rather something more mysterious and foggy in nature. But certainly, other parts of the book highlight the quotidian in interesting ways, like when Hiromi writes of giving plants in Southern California—plants for which she doesn’t know the name in some cases—Japanese names that she and her daughter can use. For this part, I felt it was important to include the actual Japanese names, but to also given readers the English meaning of these names. I love the image Hiromi gives of this scene: “As I diligently assigned names that wouldn’t make sense to anyone but my daughter, I wandered about the springtime wasteland, feeling like I was the famous botanist Makino Tomitarō, washed up on a deserted island.” Makino is the central figure in the history of Japanese botany. I love the idea of Hiromi picturing herself as a new Makino!

Pioneering Botanist Makino Tomitarō. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Dante Silva: Much of this collection is concerned with how we look at (and listen to, learn from) the world around us. I loved “Baobab Dream,” wherein Hiromi considers the classification of the Baobab. “I feel bewildered by it,” she writes. What have you learned as you worked on this collection, about how we come to know what we know? Was there more that bewildered you (either of you)?

Jon L Pitt: One of the things that drew me to this work was the way in which Hiromi demonstrates the arbitrariness of plant classification. There is so much in the book about the difficulty in identifying plants by sight, and how even if you get a general sense of what kind of plant it might be, sometimes there are so many similar-looking species within the same genus. Something Hiromi returns to several times is the change in plant classification to the APG (Angiosperm Phylogeny Group) system. This change in scientific classification really seems to bother Hiromi. She writes how “within the APG system, the Liliaceae family was shattered into tiny pieces, and separated out into a number of families with names that sound incomprehensible to me, like the Agavaceae family, and the Asparagaceae family, and the Amaryllidaceae family. It’s like spiders scattering when you turn on the light, or some kind of pointless pissing contest.” It is bewildering to think that what seemed to be a relatively stable and scientific form of classification can change so dramatically. As I worked on translating the book, I had this image of Hiromi out there “in the field,” so to speak, walking around the riverbanks of Kumamoto and the back alleys of Tokyo with a botanical field guide in hand, crouching down to inspect each small flower along the way, trying to figure out how to identify each one. And then you have this group of scientists in a laboratory somewhere studying the deep history of genetics and DNA of plant life, and changing the names and family groupings accordingly. It’s almost a story of citizen science coming up against big “S” science, if the citizen scientist were also concerned with poetics! The state of bewilderment that arises in Hiromi’s work on plants is also largely where its poetry emerges.

Dante Silva: You’ve previously stated that you see this collection as a work of philosophy. I’m curious about a phyto-philosophy, and the recent (for some) turn to the more-than-human as we respond to human-induced calamity. How, if at all, does the collection speak to these tangled, muddy, messy matters?

Jon L Pitt: There are subtle moments in the book where Hiromi discusses human-induced calamity, like when she claims that people in Japan can no longer pretend the country experiences a clearly defined cycle of four seasons, or when she critiques agricultural practices in California, or when she discusses “invasive species.” But I think the most radical aspects of the book don’t stem from any kind of obvious call to environmentalism; rather, the book pushes us to think not only about plants, but think with and even like plants. It’s absolutely a philosophical move, one that has implications for questions of environmental and racial justice.

There’s a great book by Jeannie Shinozuka titled Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950, that maps out how the histories of plant migration and anti-Asian racism in the US are entangled. When I read Hiromi’s work, I feel the weight of this history, and in Hiromi’s attempts to reclaim (or at least rethink) the very idea of “invasive species,” I see a poetic response to the immigrant experience in Southern California that brings us back time and again to the environment. I’ve argued many times that Hiromi’s work deserves to be part of the conversations happening in the burgeoning field of Critical Plant Studies. I teach this book alongside works by Robin Wall Kimmerer, Michael Marder, and Natasha Myers. Just as there are many, many kinds of plants, so too are there many, many kinds of plant-philosophies. Hiromi’s is a profound one, a poetic one. It’s a kind of autotheory that looks for the self among the trees and the grasses.