Eric Sneathen’s Don’t Leave Me This Way — published today — takes an expansive look at the AIDS epidemic and its (ongoing) aftermath. The collection is an interrogation of this history, as Sneathen collapses familiar markers of place, person, and any conventions of “normalcy” to move towards something else (“I’ll call it ecstasy,” he writes). In Sneathen’s words, “each poem is a room of sorts, a sanctuary of objects, privacies, and associations.” All of them resonate.

Our conversation below is similarly expansive — we discussed lyric intimacies, poetic collage, and what a collective project of sexuality could look like. Make sure to order your own copy of the lush and lyric Don’t Leave Me This Way here.

—Dante Silva

Dante Silva: I wanted to start with the form of your work, which I loved. There’s a collage of sources from the historical to the contemporary — you work with archives that are makeshift, not necessarily “solid.” Could you speak more about the process of amalgamation? How did you construct these poems?

Eric Sneathen: The heart of the book is the long section of cut-ups in the middle, which is collectively titled “I Fill This Room with the Echo of Many Voices.” This is a line I borrowed from Derek Jarman’s classic AIDS film Blue. When I heard these words, bathed in Jarman’s azure light, I recognized my own project: each poem is a room of sorts, a sanctuary of objects, privacies, and associations.

The archive that informed these poems was idiosyncratic and intuitive; I don’t remember the names of all of the texts that I brought into these poems over the past decade. The basic procedure, which ended up being somewhat time-consuming: I would read books and passages about gay life in the late 1970s through the mid-90s, pulling from them quotes of perhaps 100-150 words. I’d then carefully distribute those words evenly across fourteen lines, print out the pages, cut them into even quarters, and shuffle them together with other passages that I had similarly manipulated. I then transcribed what the shuffled passages revealed to me. When the parts came together to create something unintelligible at the seam, I allowed myself to create something inspired by what I saw. I would then read these transcribed paragraphs, listening for personal or historical narrative, lyric intimacy, suggestive imagery, surprising turns, and intense emotion.

The poems are the result of a kind of sedimented listening, with many voices, many histories and perspectives layered on top of one another. The intimacy of these poems—which is only mine in a qualified way—twists and turns and writhes—the proverbial can of worms that is the AIDS crisis.

DS: I also wanted to talk about Gaétan. You write, “[Gaétan] Dugas existed among and between a series of phantasmic avatars. I became haunted—recognizing his faces, moods, and manners at times and places where he had never been.” Could you say more about writing (to/from/about) Dugas? What intimacies were shared between you?

ES: First there is the name: Gaétan, Gaetan, Gaëtan. Depending on where you’re reading about him, one or another spelling may be used. I have chosen to replace all spellings with Gaétan, following the scholarship of Richard A. McKay. In his study, Patient Zero and the Making of the AIDS Epidemic, McKay does the important work of examining the journalism that bolstered the posthumous reputation of Gaétan Dugas as “Patient Zero” of the AIDS epidemic in North America. People looking for more information about Dugas should definitely read his book. They may also be interested in this clip, which includes footage of Gaétan Dugas and activist Paul Popham.

It’s hard for me to answer your question fully. The poems, I believe, are a record of the intimacies I shared. I would invite people to read the poems as lyrics and dialogues, if possible. Many times, when scanning the transcripts produced through the cut-up procedure, what I found most arresting was the intensity of the response. I perceived judgment. I felt guided and encouraged. Gates were closed. Sensations were swiftly spent. Another way to say this: I thought, when I began this series, that I might be able to channel Gaétan. Instead, I practiced conjuration and grew into that practice. What kind of attention or skill attracts language from the other side?

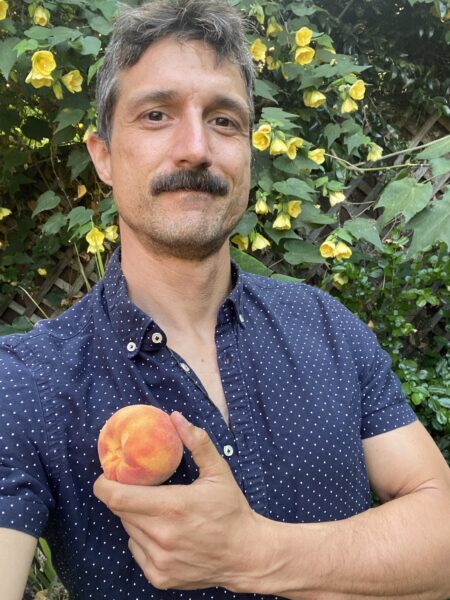

DS: So much of the collection is concerned with the body, particularly with the poet’s promise to “tell of thee like flesh forever.” The cover struck me as having a similar impulse. Could you speak to its significance? What was it like to collaborate with Gwenaël Rattke?

ES: Let’s gush a bit about Gwenaël Rattke! I have loved his work for years, and it was simply a dream come true to have an original piece of his on the cover of this book. It’s sexy as hell, which feels right for this book. But it’s also the vintage quality of the image and how the figure is duplicated. Don’t Leave Me This Way focuses on Gaétan Dugas, certainly, but it is also about Randy Shilts, the journalist who cast Gaétan Dugas (or a version of him) as the villain of his bestselling history of the early years of the AIDS epidemic, And the Band Played On.

When I consider Gwenaël’s image, I think about this doubleness, how their stories are entwined, inverted, manipulated. Gaétan, especially, has lived on as copies of his historical self—as the scourge of San Francisco’s bathhouses, as a singing ghost in John Greyson’s Zero Patience, as a bellwether in Brad Gooch’s The Golden Age of Promiscuity. I feel like Gwenaël’s image—and his work more generally—emphasizes the iterative, excessive, and even sublime dimension of sexual cultures.

DS: In the poem “Red and Came Ripe Throughout My Day Here” you write, “Me hard enough to blow this load longing / For creatures seeping their filth drops down / Red and came ripe throughout my day here / I’m ready (never cleaned).” The words “filth” and “cleaned” stand out (both with their own connotations, particularly in the context of a “criminal” sexuality).

ES: I’m so glad you singled this one out. This is a poem dedicated to Ted Rees, and it incorporates some of his pornographic writing. I was glad to incorporate some of his writing into this project, as a token of friendship and camaraderie, but also to suggest a commonality in our poetics. In very different ways, our language use has brought us into conversation with history, politics, philosophy. Sexuality—queer, frank, impolite—is one way we both coordinate these vectors in our work—a project we share with many, many others. Right now, the collective project of sexuality—as a potential site of creativity, curiosity, and justice—feels desperately urgent. Queerness is being criminalized all around us. But I think of pins Zach Ozma has been selling—with three angels tooting their horns, the words: MY GUARDIAN ANGELS ARE SEX PERVERTS!!!

DS: I see Don’t Leave Me This Way as an intervention in historiography and its discontents, an alternative to the histories we’ve been presented with (ones that are concerned with a static past and present, and preclude any intimacies between the two). José Esteban Muñoz wrote, “The here and now is a prison house. . . . We must dream and enact new and better pleasures, other ways of being in the world, and ultimately new worlds.” What worlds are you looking towards?

ES: I like what you’ve suggested here: that we might live in a world in which the past and present do indeed share intimacies. Through my academic scholarship, my work supporting New Narrative over the years, and my time with the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco, I’ve been lucky enough to find ways to contribute to making such a world more possible. Muñoz is an idealist, of course—but he cautions that idealism ought to be of the informed variety. Idealism is informed by the precedents of the past. Queer moments—ephemeral, suggestive, awkward—are poetry, of course, so I’m always looking towards poetry. With this book, I’m listening towards it. I hope others hear something of the revolution Muñoz suggested to us.