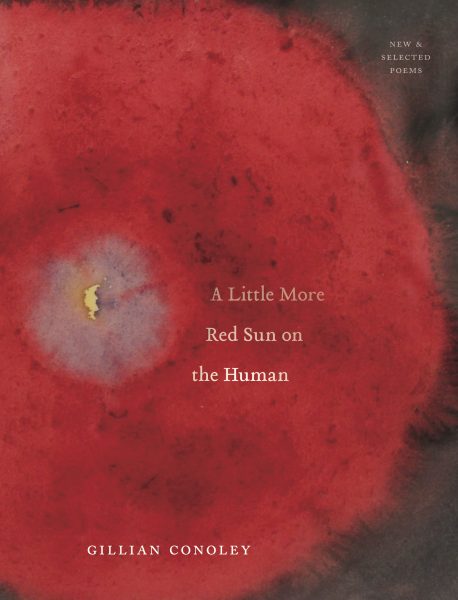

A Little More Red Sun on the Human: Gillian Conoley on Her New and Selected Works

Here at Nightboat we have the pleasure of sharing with you all A Little More Red Sun on the Human, a collection of new and selected poems from Gillian Conoley. This collection features the classic and southwesterly “The Invention of Texas,” a poem originally from Some Gangster Pain with Carnegie Mellon University Press, alongside a selection of Conoley’s other work that spans across many years and landscapes. A Little More Red Sun on the Human both continues and eclipses the vibrant, illustrative, and historical work that Conoley’s poems have been invested in for so long. Following the curation of this veritable beacon of her decades, and in the midst of infernal Californian winds threatening her home state, Gillian was kind enough to speak with me about her process of curation, the unique angle and scope a collected works offers a writer, and about the “American” presence—a feature that’s ubiquitous across her texts, and how it has been–and is being—embodied in her poems. “I’m not sure what ‘American’ means anymore,” asserts Conoley, “only that it is in a great upheaval as a term, which is good.” Read more below!

—June Shanahan

June: Putting together a book of new & selected works seems like a truly singular experience as a writer. There’s so much to consider and, I would imagine, the process opens such a reflective space. What was this whole process like for you? Did anything come up that was unexpected?

Gillian: Yes, a distinctive experience: at once difficult, unusual, strange, joyous and ultimately satisfying. From the beginning I knew I wanted to do something different, to make a new book of all the material rather than a sort of “greatest hits” selected. I love the arc and trajectory of whole books—why not try this with a new and selected? I sought out advice. I sometimes felt lost and completely unmoored. My first impulse was to include very little of the early work but the best feedback was to resist presenting or favoring only specific aspects of the work: say, a certain use of the line or a particular way of working with syntax. A dear friend convinced me it was far more interesting to let readers to see the variousness: the “oh, she did this, and then she did that, and then that.” So I gave up that “self-curatorial” sort of desire quickly, and that brought its own kind of freedom.

Over the years I’ve developed a way of writing poems that tries to emphasize practice over product, so I realized that in making a new and selected I needed to honor that practice, too. So no matter how foreign some of the early work might have seemed to me, I let it come back to me.

JS: With this newly assembled arc of your work before you, what kinds of things did you notice about your own work, its progression and morphologies in form and content? Did you find yourself more critical of your older work alongside the section of new poems or is there a harmony there for you?

GC: Both a harmony and disharmony, which I expected, as over the years my work has changed a lot, which I hope it continues to do. I’ve worked in different modalities, and experimented, though I could also see some constants. The first two books have a more stable “I” narrator and a voice that carries the idiom and vernacular of rural Texas, where I grew up. I was a bit surprised at how strong it was, hearing that again, a sense of frontier and the way people in my town spoke. This was so very different from later books, though the later work—especially in particular poems—are still haunted in places by an originary idiom. I went through this experience where I had to become friends with the persona in the early work: she seemed like an alter! This gave me the idea of thinking of the trajectory of the whole book as novelistic, since in the beginning there was this very present sort of narrator. To continue tossing out the notion of the usual selected, I removed the titles of the original books, and created new section titles. The first two books appear in one section. In terms of form, early work is composed in a narrative/lyric mode, flush-left margins, and yet one senses a kind of unrest within the form that creates a tension: the early poems have a sense of song, place, unrest, a desire to escape the boundaries of landscape and gender. Then postmodernism comes along and blows everything up—the work becomes more fragmented. Syntax is cut loose to float more freely. All gets more cinematic and roving. My interest in the page as a non-neutral force starts to show up. White space—playing with durational time on the page, making a new music that, for me, was just not possible in a justified left margin poem.

What I was happiest to see was that all along there are central motifs through the body of work: fallen democracy, gender, race, the relations between individual and state, spirit and matter, love. In the very first poem in the book issues of race and colonialism and possession of landscape are there. I hadn’t read the early work in so long, so it gave me joy to see that.

JS: Outside of poetry, your life has taken you many different places, through different careers, jumping coast to coast, etc. Can you give us a sense of that story and how that, too, may have informed your work and the way it’s laid out here in “A Little More Red Sun…”?

GC: I’m interested in motion and restlessness and the particular regions of the country and the globe and the universe. There’s an early line in one of my poems, “Live in one town too long, and a lush plain grows inside you.” I loved growing up in a small town and the resultant appreciation of eccentricities in people, a love for community lore and elaborate and digressive storytelling. I would not give that up for anything, but from an early age I also knew a deep desire to escape pretty much all confines. I’ve also loved living on the American Eastern and Western coasts, New Orleans, different periods abroad, especially in Spain. Traveling keeps one alive to change and awake to stimulus and hones and disrupts perception and consciousness. There is also something to be said for stability, too; regularity and routine can also provide one with a security that allows for wildness in the work. In terms of careers, being a journalist when I was young gave me discipline and a strong work ethic. There was a blank page every day. So “writer’s block” has always seemed to me to be a sort of romantic notion. I allow myself to play and fill the page. Journalism in the end was too formulaic and restrictive, and I find the notion of objectivity a ruse, but it did teach me the power of form and concision that I’m grateful for. I still love to edit and proof and sharpen. The Associated Press guidebook was a wonder and a fount of rules of grammar and punctuation and syntactical construction. It left a huge imprint. You have to know the rules before you break them.

JS: A consistent thought for me, from your older pieces through to your newer work, is that these poems are very American poems. They’re situated often in these dusty and sometimes sweet berry-laced spaces. I’m curious, what ‘America’ do you think is kneaded in your work?

GC: This is a very interesting question as I notice that when I hear the word “American” I wince and flinch. It’s such a difficult, divisive time. We have much to be ashamed about historically and currently. I’m not sure what “American” means anymore, only that it is in a great upheaval as a term, which is good. Obviously white people have a lot of work to do. I’m not saying that I am doing it right, and I can’t say who is. It is shameful that there is a whole body of work by white people in which race is not even addressed. The canon must be blown up. Goodbye canon and good riddance.

But to answer your question, if there is a sense of the country, of “America” in my work, I believe it has a great deal to do with music. My parents operated a small town radio station, and there was a lot of live music on weekends that we all danced to in large, old halls, all generations, often racially mixed. The dance steps were complicated syncopations and the crowd moved in circles through the halls. The music was country western, soul music, Mexican polka, rockabilly, rock and roll. All of these musics are mixtures of one another, except for soul music that of course came from gospel and the blues.

The other sort of “stream” that contributed to this sense of an American sound likely has to do with the wide variety of languages and idioms and dialects one could hear in my town, which had very rich soil, an agricultural town that drew a large immigrant population. It was founded in the 1800s, had a railroad, and a population of around 10,000. Until Wal-Mart killed it, the town was a functioning economy of small independent businesses. A lot of my friend’s parents were first generation immigrants. One could hear Polish, German, Spanish, African-American Vernacular English, “white trash” dialect, and a sort of mixture of all of this that was the town’s own particular idiom. It was a chorus! In a town like that everyone knows one another in inescapable deep ways. It was a knowable community. Of course there was racism, and black and brown people knew a lot more about white people than vice versa. There was a lot of interracial dating in my high school. Gay people were not out, it was too scary and Texas machismo and gravitas and strict boundaries of masculinity and femininity were fierce. I was child during the Civil Rights Movement, a teenager during Viet Nam.

JS: Your poems are also deeply invested in the border, which subsumes the figure of the other, the diaspora, and (im)migration. I wonder how you might think the evolution of that theme in your work has been influenced by the unfolding of events over time at the border parallel (or maybe perpendicular) to your poetic workings?

GC: You can’t grow up in Texas without a keen sense of the Southern border. And it’s not the sense of a strict border that is trying to be drawn now. There was a loose, open, fluid sense of the Mexican border, even in Central Texas. I crossed a lot, as a child, a teen. The border was just a highway with stops you had to cross through and maybe the car would be searched, but usually not, just a few questions as to what you had and what you took or brought in. Border towns were places of mutual commerce and community. People worked on one side and lived on the other. In elementary school, Spanish was mandatory from the 4th grade on, though on the American side Spanish-speaking people were not allowed to speak Spanish outside of class on the school campus. Immigration was a constant. What’s going on now is completely antithetical to my experience as a child and adolescent.

Today’s diaspora, immigration, refugees, all a worldwide movement of turmoil and pain. We have to look beyond America for answers and solutions. My poetic workings have become increasingly open over the years and there is a rejection over product in favor of process. I’m not sure how much this has to do with the border per se, but I wouldn’t reject that idea as being formative. Nor would I reject the idea that boundaries are problematic for me having grown up female.

JS: Do you have a sense of what’s next for you? How do you think putting together this collection has oriented your next works?

GC: I was working on a new manuscript when the new and selected project came up and so now I’m just beginning to return to it. The title is The Next Next World and it’s located in the future. The book is an inquiry into how humans may form community with inevitable technological advances in AI, robots, avatars: how human perception and consciousness may change or adjust or remain in relation. How we will survive the anthropocene. I live in California, in the Bay Area, where the wildfires create an alternate sense of apocalypse and then once they are over, we experience a vast inexplicable sense of forgetting, as the physical beauty of the place is so striking, and each year, it returns in all its glory after a high degree of toxicity and terror. I’m not interested in bemoaning the anthropocene or what we are now calling in California the pyrocene. I’ve had a lifelong faith in community and love of community. I was born in the aftermath of WWII and have lived with nonstop war ever since. The Cold War was war. Democracy is a beautiful dream. We have a republic, if we can keep it, as Benjamin Franklin said and as Nancy Pelosi has reminded us. I’m not ready to give any of that up. So all these ideas are sort of floating around in my head as I work on this new manuscript. I want to remain open to whatever poems might come, and especially in whatever form they might come in. I’m very interested in poems completely breaking down to discover what they are. I believe in attending to the work, rather than “writing” it, if that makes sense. I’m not interested in this book being “a project.” I want to read a lot and do a lot of research and then forget it as I work. So maybe you (you as in potential readers, you as in fellow humans) could please just forget all I just said in describing the new work.

Order your copy of A Little More Red Sun on the Human here!