Happy Birthday to Akilah Oliver!

Akilah Oliver (1961-2011) is remembered for her fiercely intelligent and ambitious writing, which sought to do no less than expand the boundaries of an African-American literary dialogic tradition in its troubling of “Blackness,” “femaleness,” and “homogeneity.” She was a mother, a queer woman, and a true renaissance woman, who co-founded the feminist performance collective the Sacred Naked Nature Girls, worked with the Los Angeles Poverty Department (a theater troupe which worked with the homeless), and was a member of Belladonna* Collaborative, a PhD candidate at the European Graduate School, and a professor at Naropa University and Pratt. She was the author of A Toast In The House of Friends, the she said dialogues: flesh memory, and the chapbooks An Arriving Guard of Angels, Thusly Coming to Greet, The Putterer’s Notebook, a(A)ugust, and A Collection of Objects.

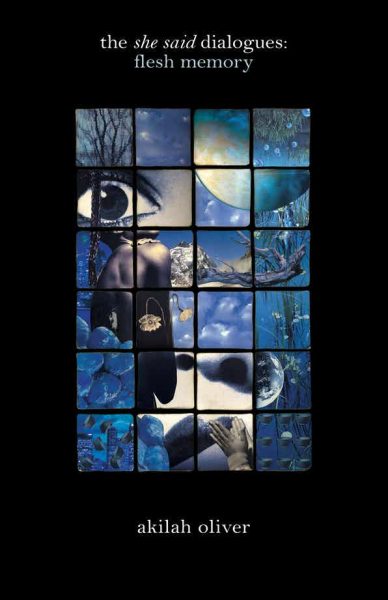

In celebration of Nightboat’s republication of Akilah Oliver’s the she said dialogues: flesh memory, and on the occasion of what would have been her 60th birthday (on April 18), we asked four poets—S*an D. Henry-Smith, Aristilde Kirby, Zahra Patterson, and Tiana Reid—to respond to the she said dialogues for the Nightboat blog.

S*AN D. HENRY-SMITH

flesh_meditation_memory

Throughout Akilah Oliver’s the she said dialogues: flesh memory, she lays bare her intention & means of experimentation: “vulgarize the living sentence,” & later on, “create a theoretical language to situate the emotion. i admit none of this. the exhibitionist just likes to expose her scars.” She is poet & theoretician, inseparably, insurmountably—all decisions are guided & informed, the results of embodied study. She instructs, providing the groundwork for flesh memory, exacting its methodology, adamantly & humbly placing into practice in the same effort. I think of her name set in lowercase on the original cover, replicated in this republishing & her use of lowercase “i” as a bowing: to those she is speaking w/ (real, fictionalized, forgotten, remembered), to the forces that speak through her. Authoring in lowercase is to make way for something outside of oneself. Flesh memory as practice requires this lucid attuning, to be dangerously alert, yet knowingly, decidedly vulnerable in order to connect to something greater & often disturbingly unacknowledged.

“why wouldn’t we all immediately have a common reference. where is the national tongue. the informed language for this thing called slavery. i don’t know of anyone who knows the names of their great great great great grandfathers. not the mythic ones or adopted ones. the exact people who birthed you. i don’t know of anyone who knows the faces of their grandmothers’ rapists. not any face. the face. i don’t know anyone who can sing an old freedom song. where are the stories of the torture. What did women do with their hair. where are the seers. what the hell does raw cotton feel like. bales & bales & generations of it.”

There are no question marks to spare. She is demanding reasoning & results for elusive questions. She comes equipped w/ ante-empirical evidences to address them. Akilah Oliver excavates localized & imposed histories (the personal & globalized as entangled) using Black analysis—sharp, colloquial, rhythmic, tasted, religious meditation & critique, sensory & erotic awareness & feminine divinatory measures—to name a few. Sop up the spilling blood to conjure a love unfathomable: remember it as it was sung to you in many musics, necessarily bound to body & spiritbody; these are not separated either.

Flesh is multivalent & multimodal, memory, too by provided definition. Flesh memory allows insight into experience, contextualizing a gesture with the knowledge of the present. She says, “on the way to somewhere the little child said it’s such a nice town. they must be hiding something.” I so clearly see the child looking out the sedan on a pleasant & clouded day, suspicious of this inconsistently beautiful world. This grows into keen, searing, never-just-playfully-missive-but-black-humored characters: “the steamy holy water in which we try not to drown & close to floating is the saddest kind of survival” & “don’t mind if jesus is my friend. i want my friends to answer when i call” & “i want my pen to flourish. fancy deaths. off shoulder strapless black. cliche” & “i need to fuck myself in such a way that the moans eat me alive” are observations & locations on a map of potential memories & desire, finding themselves articulated as maybe-truths (not that the truthfulness matters, so much as the seriousness you encounter them w/) in the form the poems take.

The text block & polyrhythmic line—unabated, staccato’d, onomatopoeic w/ mystic precision—generate memory as breathless in rapture, producing clarity in thought, pondering & feeling through a broad stroke of experience. I mean, it goes w/o saying: she’s rapping. spittin. Don’t you hear? I can’t possibly be alone: the doubling of her voice over the internal voice of the reader, slipping into her syncopation as one moves through the experiment in experience in realtime(s), now & then & once before & yet to be. You hear her, don’t you? “how she sing like that. how she know just then is when i need to cry. it’s the reciprocity of beauty that makes me doubt my self,” she says. I hold the mirror asking back at 2am, locs piled up & fallen onto one side, lost in collective wonder, wet w/ potential memory. I hold her weeping book, wet w/ our commingled tears. Tonguing down the depicting moment rendered in language in order to measure, shrink & expand time, by disrupting language, linearity, binary equations, her playing field living & breathing as it comes back to life, builds itself into the ethereal & the material, the everreal, encountering the world more intimately.

In dialogue, she is never alone, she will not allow us to be alone, she invites us in. An exchange of listenings, an offering of presence, looking back to look beyond, to better understand the inter-/intra-/extra-personal. Communing w/ past selves & w/ sisters. Dialogue is an attempt to know as can only be achieved through the means of being together, listening. She said it & she listened. Dialogue is to witness. & she’s still witnessing, refusing to go unheard. Why else all this work of “Refashioning the Black female tongue” if not to alter how we ought to be hearing: boundlessly. (& it’s safe to say I owe her everything. Leave my ampersands in her honor, making use of another of the tools she uses to close the distance between ideas, amplifying an immediacy, an urgency for intensive reflection. I bow in my own name. Akilah, I hear you, as you speak to me as I am most inclined to hear.) The strange & demanding work of the poem embodied, sacrifices for inventive communication. Ancient & present knowledges, necessary a-synchronicities. & i must begin to say bye now or i may never leave

ARISTILDE KIRBY

Please click open to view.

ZAHRA PATTERSON

reading akilah oliver’s flesh memory

The penultimate poem in Akilah Oliver’s the she said dialogues, “Lover: I,” closes with the lines “duplicitous experience. / that was a duplicitous experience you said when we got off.” The lines send me back to Oliver’s opening statement in which she explains her task:

I think for me part of the importance of this text is situated in the ongoing work I’ve been doing in performance with the concept of flesh memory as it relates to a critical interrogation of the African American literary/performative tradition. That tradition (what I consider to be crouched in the sacred/profane dichotomy, a dichotomy which Du Bois called “double consciousness”) is an outgrowth of a necessitated survival mechanism, which has split “Black consciousness,” not only in terms of the outward, homogenous mask donned as a form of cultural preservation, but also in terms of the internal discourse: what is permissible to speak. (xi-xii)

The duplicitous experience takes place in a dream on a boat ride across a bay. It is that moment when a lover rejects her love in a stranger’s presence. One’s instant self-subjugation results in the dehumanization of your love, of your lover, of yourself. Our subjectivity deceives us and projects a reality that endangers our survival onto the canvas where we draw our lives. Thus, Oliver expands

Du Bois’ work by interrogating consciousness beyond the binary. Further down the page she says, “I see the dialogues as a part of the emerging outsider tradition in black literature which restates memory and identity in a post-Civil Rights framework. A framework which is multiplicitous.” She illuminates a hall of mirrors.

I am twenty years younger than Oliver and about her age when she wrote the she said dialogues: flesh memory. I feel our traumas merge as I time travel through a lived history of desire informed by a cultural history of limits that we constantly cross and expand. In her foreword, Tracie Morris states, “Akilah makes plain the constraints of real time, and yet there is friction, and potentially freedom within these lines.” Friction’s potential to summon freedom reminds me of Toni Morrison’s foreword to Sula, in which she claims, “Female freedom always means sexual freedom.” Oliver’s text rubs against that potential for freedom. I permit her to disrobe me. She says. I respond.

reading akilah oliver’s flesh memory

I.

The language activated in the body’s memory, she says. you don’t know that I am awake when you slip away to pee in the middle of the night. back under the covers your left hand lands softly on my left shoulder. my synapses dispatch bolts of desire. warm and painful.

II.

compartments of space invented to live in, she says. i stand at one end of a hall and you are at the other end. 30 miles away. 2,000 miles away. fourteen years pass. i reach for you and sand shatters my windshield. the air is gray. baroque shadows cast an ominous mood. in a black and white film, sifting through sand and glass i can’t see you but your wild laugh echoes.

III.

bristly hairs rub lavender, she says. walking the corridor lined with artists’ studios i see danielle scott’s bristled black pink vagina among others. unapologetic ovaries and boisterous lips decorate the floor. runway vulvas like designer shoes dance in the display à côté.

IV.

slick taste of cocaine chorusing down throats, she says. you call it a snowcap. sprinkles on cigarettes too. smoke spiraling blizzard. memory splintered fragments. delighted i land on your bed as if from above. we journey. drive to the cyclops. detour with sirens. do a death dance.

does a scream sound if the cause is illegible?

V.

evil is everywhere etched in minstrel. dance, she says. like hot coals between mulatto toes i perform assimilated love. against the backdrop of a foreign city. drums beat in the streets. i returns to the middle ages. before the modern world i am tattooed at a military ball stretched in four directions. driven by the whip. no notion of your role.

VI.

& freedom is more than just some people talking, she says. freedom is more than shattering ceilings. freedom looks good but it’s not just looking good. freedom is seeing your neighbors free. freedom is seeing the world free. black trans freedom is indigenous elders freedom is asian women’s freedom is queer latinx freedom. freedom is movement. freedom is migrant. freedom is emigrant. freedom is accessible. freedom is love. love is making space. freedom is growing. love is preservation.

TIANA REID

pussy/fucking

“The bluntness of the sexual references (often linking the sacred traditions [church gospel/icons] with the profane [pussy/fucking] is one way the dialogues seek to work as a kind of insurgent text within the African American literary tradition.”

—Akilah Oliver, preface to the she said dialogues

Her poetry grabbed on me, stuntwoman that she was. I’m in a nightmare again, that look in the book’s eyes. Flash, remember? From the back. Much later, the ember it.

What lives in the body is beyond unthinking flesh, beyond hot tinge, beyond sensual sedition. She grabbed on me from the back, in the big-laden bed. Much later, I would member it, cringe at the sound of she: memory-eating honeycomb, curving bloodwork, inglorious wetness, conceptual backflip, apparitional trauma-drama-rama.

But she, sulking suck, she was souring anger, depleting dog-sinning property lines. What the actual foreplayed feelings?

Fuck this ravenous world—boudoir and brimstone, sprung poetics, sonic blackface, groping riot. I train myself to feel it, flooded like a blueberry pancake, raw like an accident-skinned guttural function.

Each enunciation of pussy is a grotto, giggling into a Babylonian panic, somewhat hogtied together.

…a “she said” beckons live, laugh, lie

or, on better days: salt, stone, sobriety.

****

S*an D. Henry-Smith is an artist and writer working primarily in poetry, photography, and performance, engaging Black experimentalisms and collaborative practices. Wild Peach, their first full length collection, was published last fall by Futurepoem.

Aristilde Kirby is a being constellation of given human category [poet]. She has published this [Daisy & Catherine (Belladonna*)], that [Sonnet Infinitesimal / Material Girl (Black Warrior Review & Best American Experimental Writing 2020)] & the third [Daisy & Catherine². (Auric Press, Summer 2021)]. She has a master’s degree from the Milton Avery Graduate School of The Arts, Bard College.