A Conversation with Wayne Koestenbaum, author of Ultramarine, and Nightboat Fellow Snigdha Koirala

Happy publication day to Wayne Koestenbaum’s Ultramarine, the closing title in the acclaimed trance poem trilogy (the previous two collections include The Pink Trance Notebooks and Camp Marmalade). To celebrate this milestone Nightboat Fellow Snigdha Koirala speaks to Wayne about desire, void, dreams, and cultivating a steady kind of pleasure in his new book. Take a look below!

Snigdha: As a reader, there’s an element of following the language—of letting the language take control—when you enter the stacked, compressed world of Ultramarine. And there seems to be a similar experience for you as a writer as well. You write, “obedient to language’s/ stacking decree—words/ must be stacked.” There’s autonomy and agency to the language—a kind of magic, even. Can you speak to this process of writing—what was it like to engage with the language in this way?

Wayne: I’m grateful that you notice the centrality of stacking to Ultramarine. Although much of my writing life is spent in the domain of prose, I remain faithful to poetry’s possibilities in large part because of the pleasures involved in lineation, especially short lines. The moment a line break happens, and we’re thrown, as readers, into the next line, a defamiliarizing haze takes over—the “magic” that you mention. The new line is haunted or indebted to the line that came before, but also free to ignore the previous line, and shirk all indebtedness. Stacking the stanzas of Ultramarine together, I tasted the freedom of dis-affiliation, canceled connection; the new stanza, or micro-poem, separated from its mates by a horizontal line, had no obligation to the preceding events and declarations. As in the diary films of Jonas Mekas (this weekend at Lincoln Center I’m going to see Mekas’s magnum opus, As I Was Moving Ahead, Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, a nearly five-hour compendium of diary footage he shot between 1970 and 1999), Ultramarine attempts to stack together, through a juxtaposition procedure at once tidy and aleatory, a kaleidoscopic selection of diary snippets from several years of notebook-writing. Brief glimpses of beauty is all I ask for. Maybe not even beauty. Maybe just mirth, or arousal, or melancholy.

Snigdha: Desire is, of course, a tremendous thread running through the book. I sensed this not only in what you write about (sex, sexuality, food, colors) and the playful, plump language you use, but also in your writing process. In your conversation with Tony Leuzzi, you talked about your editing process, explaining, “I would look at one of these transcribed pages and search for the words that looked good. Literally, the way I would with a painting. I studied the page, blurred my eyes a little bit and waited for something to jump out.” There’s a visual element to this, as you point out, but also something very visceral and immediate about it. Can you speak to this viscera, and how your own practice of visual art informed it?

Wayne: The revision of Ultramarine took place mostly while I was standing up. Or that’s how I remember it. Standing at the kitchen counter, or next to the piano. Looking down at my typescript transcription of my trance notebooks. Surveying the pages neutrally, objectively, curiously, without great attachment. Seeking the nuggets of truth, comedy, indexicality, concreteness, strangeness. Searching for the weird words. Just like when I’m looking at a collection of marks I’ve made on a piece of watercolor paper. To be “topical” and maybe too didactic, I’ll suggest that the watercolor paper is covered with ultramarine Flashe vinyl paint, but unevenly applied, and I’m investigating the areas where the difference between thinness and thickness of paint suggests vestigial or latent figures, lines, vectors. Then I’ll take an acrylic marker and draw the lines I vaguely see. Then I’ll decide I don’t like what I see, and I’ll cover the page with Naples yellow Flashe paint, combined with ivory Flashe, or parchment acrylic (I love that there’s a Liquitex paint color named parchment!). Before the pale yellow paint dries, I’ll take a watercolor pencil, perhaps Payne’s Gray, or carmine, and draw/write on the yellow scrim to bring back into visibility the ultramarine underlayer. Always below the second or third or fourth layer, there’s an understructure of ultramarine, like sky or pond—subterranean or celestial scaffolding for the thoughts and images and memories that we pile up in stacks, planned or random, above a pool that seems like opaque night but is actually transparent and open to any illumination we can muster.

Snigdha: Following this thread of desire, I wanted to ask about the relationship between the elements of void and absence (via the white spaces, for instance) in the book and the playfulness of desire. There’s the “vowel stuffed with rosemary” and there’s the process of “relearning how to find/ shapes and narratives” in the “void,” which of course is “multitudinous.” How did you conceptualize and work toward this relationship in the book?

Wayne: The void is what I face—what we face—when we write. The void of the non-verbal. That void, however, can be molten and material—terribly actual. That void isn’t nothing, it’s just refusing (unless we force it) to speak. To wrest words from the void, we need to remember that words will come from a different place than the void. Words will come from the word pile, the language pool, which starts to bubble up when we realize that we can’t enforce a strict alignment or correspondence between language and material. Words have their own agenda. And so we can permit the word-agenda to begin taking over, while we keep staring at the material, trying to nudge the words back toward subject-matter. But if we push too hard, the material, and the words, too, will fall back into the void, and we’ll be left resourceless. So we stop caring too much, we stop insisting on perfect alignment of word and thing. And then the void starts to become populated with memories and urgencies and observations, clothed in words. This description isn’t precise. But the void is my companion when I write. And maybe I write because I want to hear what the void has to say.

Snigdha: The material form of a notebook has obviously shaped the language and structure of the book (and the trilogy as a whole). There’s also something dream-like about reading the book, moving from memory to memory, scene to scene in an almost seamless way. I wanted to ask about the relationship between the two. How did you come to it and what was the experience of cultivating it like?

Wayne: I’m glad, Snigdha, that you find the reading experience to be dream-like. Some writers and critics disparage dreams, and consider dreams to be inferior material for literature. In contrast, I love dreams, anyone’s dreams, mine, too. I don’t love them because they’re illogical and evanescent. I love them because they contain stories. If we stop denigrating dreams, and demanding that they behave normally, they relax, and begin to turn into usable narratives and images. The trick is to stop insisting that the dream story be continuous. Be grateful if you can find, from a dream, two or three actions or images or personages. Enjoy these discoveries. Watch how magical their conduct is, when you put them into a poem or an essay. For the past few nights I’ve been dreaming of a house that might be on Cape Cod or might be in New Jersey or might be a combination of several houses I’ve known or dreamt about. Inside that house are a few obligations I’ve shed or that I’ve secured. One of those obligations involves song. Another involves madness. The figure in the dream—a singer—is telling me about the collapse of her voice, but she is also denying that her voice has disappeared. To make this dream useful, in a poem, I need to put Cape Cod and New Jersey and Donizetti together with the word “withdrawal,” which recurs in the dream. “The withdrawal” is what we call the singer’s exit from performance.

Snigdha: I was struck by the following lines: “syllables/ crammed together—how much Berini-style/ sculpture is devoted/ to orgasm?” The concern with the cramming and then the orgasm (a sort of release) felt in juxtaposition with the larger project of Ultramarine. The book gathers and stacks various fragments of the quotidian, but refuses a linear beginning/middle/end or any sort of (heteronormative) climax or rupture. As a reader, you get the sense that the book is after a steady pleasure, not catharsis or release. I wanted to ask about cultivating this kind of pleasure. How did the diaristic and movement-based practice help inform it?

Wayne: Cultivating steady pleasure, yes! That’s what I keep learning from Gertrude Stein. Not that Stein isn’t full, too, of catharsis, release, orgasm, finality. I used to see a neighbor of mine at the gym. When she was doing her stretches and lifts and lunges, she would say to herself, quite loudly, “Keep going.” She said “keep going” as if no one else were in the gym overhearing her. “Keep going,” she’d repeat, in a voice slightly chiding and self-critical. Time passed, and she died. After she died, I found, in our building’s garbage area, her Smith-Corona manual typewriter, with her name on the case. I rescued the typewriter from the trash. Keep going. I’m keeping going with this story but I’m not sure where it will lead. I tried to use the typewriter for a year or so. I failed to make good use of it. I had other typewriters. I prefered those other typewriters. Eventually I put the dead neighbor’s typewriter back in the trash. Keep going. But the story of her typewriter, and the meaning of her typewriter and her lunges and her voice saying keep going, keeps going in me, maintains momentum. Maybe at the end of Ultramarine, which ends my trilogy, there’s release. Is it an orgasm, when I hand Judy Garland, in my dream, on the last page of Ultramarine, some lamb fragments to clutch? Or is it a scene of death, the lamb’s death, Judy’s, the poem’s? The poem, the lamb, Judy—they died long ago, but they keep going. I could go on singing. The way they keep going is fragmentation. Forgive the fragment, pile up more fragments, stack them up, love the fragments, don’t refuse them their off-kilter logic. I’m not creating a monument, I’m creating a machine to permit movement and growth, my own, temporarily, but also, I hope, for a reader, to whom I am entrusting, with a nervous, documentary hand, these fragments.

***

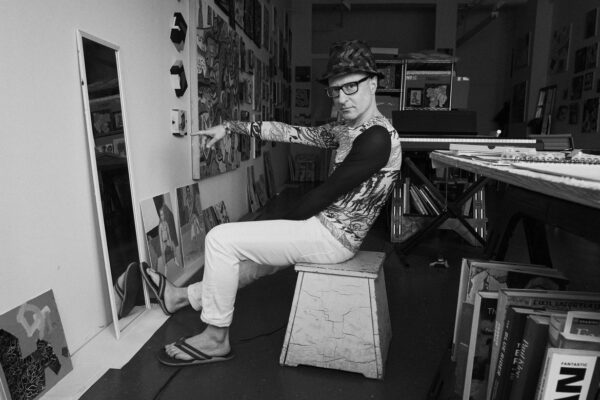

WAYNE KOESTENBAUM—poet, critic, novelist, artist, performer—is the author of 22 books, including Ultramarine, The Cheerful Scapegoat, Figure It Out, Camp Marmalade, My 1980s & Other Essays, The Anatomy of Harpo Marx, Humiliation, Hotel Theory, Circus, Andy Warhol, Jackie Under My Skin, and The Queen’s Throat (nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award). He is a Distinguished Professor of English, French, and Comparative Literature at the City University of New York Graduate Center.