A Conversation with Gabriel Ojeda-Sagué, author of Madness and Nightboat Fellow Snigdha Koirala

Happy publication day to Gabriel Ojeda-Sagué’s Madness! To celebrate, Nightboat Fellow Snigdha Koirala speaks to Gabriel about constructing the character of Luis Montes-Torres, the slippage between fiction and biography, registers of language, and more! Take a look below.

Snigdha: Madness is invested both in the construction of the character of Luis Montes-Torres alongside the construction of his poems. What was the writing process for this like? To what extent did the character inform the poems and to what extent did the poems inform the character?

Gabriel: So, Madness is divided into about 9 sections, each of which are “selections” from “books” by Lu. Each of these “books” manifested differently, some much closer to the fiction and some further. When I was generating the idea of this book, I had already started writing some of the love poems that make up the “All the Love Bush” section, and they didn’t have much of a character or persona attached to them. The same is true for some of the poems in the last sections “Some Shields” and “Last Poems.” Once I had really come up with the idea for the book, designed the character of Lu and had a sense of his character arc, I started to fill in what kinds of books and poems this person would need to write and what kinds of poems the book needed to tell its story. A really direct example of this is the “The Ocean as It Shouldn’t Be” section, which is made of these half-ironic poems about Marielito immigration. The poems there only exist because of the fiction of the character, and in the text those poems themselves are deceptive about what they “want” from immigrant poetry. So, it has this layered fictionality there. I tend to think of Madness as a soft persona, in the sense that the persona dictates certain moves in the book, but not all. Lu is clearly different from me, but we’re centered in similar ways. It’s not autobiographical, but it would be silly and false to say that it’s all fictional.

Snigdha: The book has a range of registers throughout, from the Introduction to the Editors’ Notes to the Table of Contents. How did you approach and conceptualize the meeting of these registers, and the ways in which they inform the reading experience?

Gabriel: I wanted Madness’s book, the book that the book represents itself as, to pass as a book. I spoke with the design team on using the front- and backmatter of Madness to mark this sense of a book-pretending-to-be-a-

Snigdha: I was intrigued by the book’s claim of fiction and then, toward the end before your own Acknowledgements page, a claim of truth. Madness works with this slippage between the two, exploring life and love marked by difference through Montes-Torres’s character. Can you speak to this slippage—what possibilities did it offer to you as a writer?

Snigdha: There’s a shift in style in the poems as the collection progress. And this also indicates a temporal shift in Montes-Torres’ life and work. What was the process of conceptualizing a relationship between style and time like? How did you navigate the correlation between the two? Did it inform the construction of the speculative future you present in the book?

Gabriel: This was a tough aspect of the writing, simulating aesthetic growth and change in priorities for this character. I think there’s often stereotypes about early and late work in a poet’s career. For example, speaking very generally, a poet’s early work tends to be a bit livelier, more raw, but also less ambitious, less even; a poet’s late work tends to be a bit more settled into patterns, sometimes more conservative, but is often more careful and smarter and thinking in new ways about death and retrospect (see Adorno’s essay on Beethoven’s “late style”). So I played off of that a lot, but I had to be careful not to overdo it. The first section of Madness, “Hills and Towers” is noticeably weaker in certain stylistic concerns and definitely less ambitious structurally, but its lively and personal anxieties are unmatched in the rest of the book. The arc of Madness sees Lu struggling with his work’s relationship to the political, and making various changes in style with regards to this. One of the ways I tried to simulate this arc of growth without making any too obvious or corny moves was that I made the book somewhat recursive, in that the first and last “book” mirror each other, and the second and penultimate “book” mirror each other, and there’s a big hinge in the middle of the book. In that sense, you get this feeling of Lu as a writer who developed, but also recurred.

Snigdha: There’s an element of mock and jest in the book. I love the Editors’ Notes to “The Ocean As It Shouldn’t Be” when you write how even those unfamiliar with Montes-Torres’s work had at some point come across his poem “In the Morning” because he was the only person who submitted to Kellogg’s call for poems on Frosted Mini-Wheats. What was the process of implementing the element of humor in the book? Can you speak to your motivations behind it?

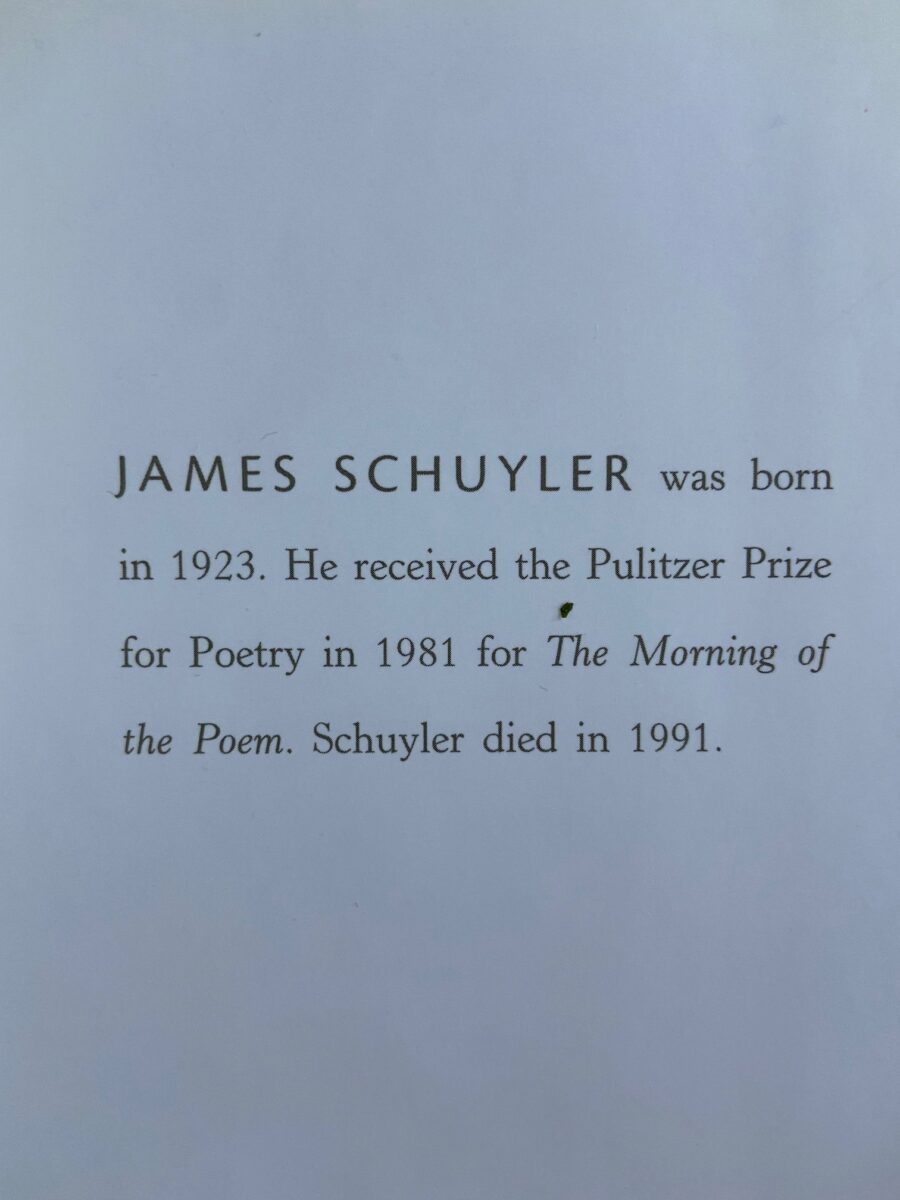

Gabriel: Earlier versions of the book mocked Lu quite a bit, and one of the concerns of the book was in thinking of him as a kind of failure. This stopped working as the writing and editing process went on, and sort of made the editors feel like cruel figures. I still wanted to give a sense of something about Lu’s life and relationship to poetry not quite working, but I shifted the ways that that might happen. I really like that Kellogg’s part haha, and I kind of tried to frame Lu’s big mental breakdown moment at the climax of the book in terms of slapstick. Part of this humor is about the tone of selected poems, being that they have to quickly summarize or even pass over incredibly dark moments of a person’s life, making them into factoids. While writng this book, I thought a lot about this bio for Schuyler that is printed on an edition of a book of his uncollected poems. It reads “Schuyler was born in 1923. He received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1981. Schuyler died in 1991.” That’s it. That’s the life according to this bio. For Schuyler? A manic depressive who almost accidentally burned himself to death, who also loved and wrote widely? And he gets a birth date, the Pulitzer, and a death date? That tonal failure is sort of darkly hilarious to me. One way of thinking about Madness is that it’s a book about the voice of that bio that would summarize this life that way and about the life itself and the work that life produced. At least, this is Madness’s ambition.

***