A Conversation With Chia-Lun Chang, Author Of Prescribee, And Editor Gia Gonzales!

I recently had the pleasure of sitting down virtually with Chia-Lun Chang to revisit some of our editorial conversations about the unnerving funhouse of American culture, Taiwanese history, and racialized identity that is Chia-Lun’s debut poetry collection Prescribee (released last fall with Nightboat). I feel so lucky to have had the opportunity to chat with Chia-Lun about genre, exophonic writing, and identity over the course of several months, and I’m really excited to be able to share these conversations with the Nightboat blog. Take a look at our interview below, and don’t forget to pick up your copy of Prescribee here!

***

Gia: In our early editorial conversations about Prescribee, we talked at length about how important humor is to your poetry. There’s something that can feel really high-stakes about humor—it’s either funny, or it’s not; if the joke didn’t land, it’s failed. But the stakes feel especially high in “Why I Am Not a Comedian,” in which the speaker “take[s] funny as painkillers…. we take funny to survive.” What is important to you about humor? What makes something funny to you? Is humor something you actively work for in your poetry?

Chia-Lun: Because poetry readings are usually quiet, I never thought too much about humor in poetry until I started to perform. Due to anxiety and insecurity, in my early years, I wanted to amuse the audience, so that I didn’t hear my voice solely filling the room. Since time feels swift during readings in public, I can’t verify if a joke lands or crashes. Once I had a discussion with my dear friend, Wendy Xu and she shared that sometimes people laugh not because it’s funny but because they’re not used to certain pronunciations or accents. Our conversation taught me to be conscientious when I read and trained me to embrace silence without pleasing the audience. From my observation, sometimes people giggle not because it’s funny but because they are uncomfortable or embarrassed or encounter unfamiliarity. In writing, in order not to take myself too seriously, I tend to apply humor to combat melancholy and discomfort.

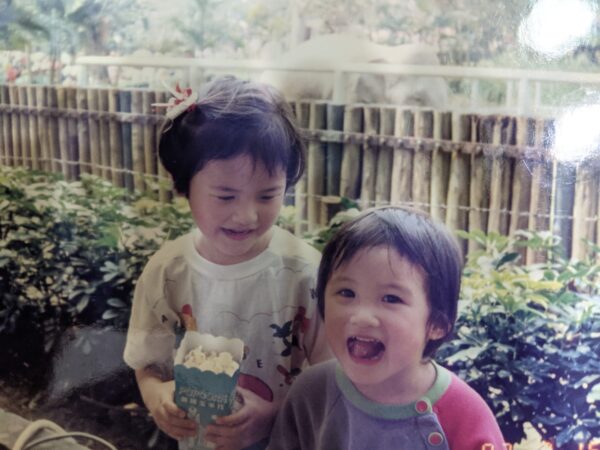

Humor plays a role in challenging, destabilizing, and shifting solidified reality. It is definitely important to me, my sister is the funniest person I know. Growing up, my family was always stressed about finances, so the jokes we shared seemed to be the only moments they could escape from that poor cage. It’s an act of love. One time my grandma admonished my sister for staying overnight at her boyfriend’s place because the neighbors might gossip and ruin our family’s reputation, to which my sister retorted, can I stay overnight at any place as long as there are no neighbors? To see my sister handle difficult situations wittily is both fascinating and heartbreaking. When my sister isn’t around, I try to imitate her.

I admire professional comedians who practice this high-stakes art form and spread joy. But I choose not to perform jokes, because, for me, humor comes spontaneously, privately, and can be painful. Because society is already ridiculous, I can be funny by merely being honest. In “Why I Am Not a Comedian,” I inspect myself and realize that being funny or not isn’t important. I enjoy creating an exciting and unexpected space, and the space is easier to arrive at through humor, a potent gateway. I still can’t resist performing a corny joke before the reading, it’s my silly way of love.

Gia: In another one of my favorite editorial conversations with you, you spoke about how you conceptualize PRESCRIBEE as a horror story or a video game—a framework that may not be so evident to readers upon first glance. Would you talk a little more about this idea?

Chia-Lun: When I was young, I read books as an escape from my mundane routine. The experience of reading is like walking through a dark and mysterious forest with a flashlight and only being able to see my feet. Every book contains many unknowns and reflections, waiting to be unlocked. The adventure is similar to exploring a maze or playing an RPG game.

The journey to the US, a massive land, varies for individuals. When I put together Prescribee, I decided to create a theme park for readers to enter, both fun and scary. I’m also interested in cultivating the emotions I wasn’t encouraged to express back in Taiwan. The theme park is an experience, I take advantage of this experience to investigate madness, anger, aggression, sarcasm, and other emotions that are considered negative. No feelings are bad because they allow me to live more fully. Since books are attached to institutions, I wanted the experience to be less academic, and less restricted. To me, reading a book, watching a movie, and playing a video game all have many overlapping impacts.

Gia: Over the years, you’ve spoken so insightfully about your relationship to English. In the tagline for PRESCRIBEE, you describe English’s use as both “foreign language and medium.” My favorite depiction comes from a roundtable you once participated in, where you said: “Now I see English as a lover since I wasn’t born to speak English. It doesn’t belong to me and it never will. May I still hang and mingle with it everyday without claiming my territory?” I would love to hear what it means to you to disavow, or refuse to claim ownership over a language. What has your experience been like using a foreign language as a medium?

Chia-Lun: English, as a powerful language, tool, and lifestyle, enters many societies and lingers in our daily communication and status, it’s unavoidable. My first languages are Taiwanese Hokkien and Mandarin, and I’ve been learning English on and off since I was 8 years old. Most people around me speak Taiwanese and Mandarin but no one really speaks English, it’s a subject only related to grades and opportunities. Compared to other foreign languages, I’m familiar with English but never as close as Taiwanese and Mandarin.

I’m most agile in Mandarin. My obsession with logosyllabic characters at school stretched into love with literature. And it’s the official language in Taiwan. Taiwanese is the language I speak at home. Speaking Taiwanese used to be prohibited and is now dying. Language is a living substance, and it’s dead when no one uses them. This relationship is personal, as I hold onto my native language as holding my elderly parents and suppressed stories, trying to preserve a piece of them in the speedy race with time.

My relationship with English is complicated. I have trouble learning the phonogram system. In fact, I gave up on connecting with English until I was in college. In an ideal world, there shouldn’t be a hierarchy in languages but some languages have no job opportunities. In the beginning, English was a skill to make a living. As time passes, I pour in my feelings and commit my art to the temperature of English. Because of my background, many people ask if I write in Mandarin: Do I translate my thoughts between languages? Why don’t I write in my first language? I don’t have an answer and it’s hard to admit I simply had no opportunity to develop my creative writing or to publish in my mother tongue. The sorrow that I don’t write in my mother tongue is mostly the fear of losing the bond with the people I was once close to, not about the languages themselves. I acknowledge the incompetence, clumsiness, and foreignness of myself residing in English, but we are not strangers. With the time and effort I devoted, I want to love English gently. I believe the purpose of language is to communicate, and English permits me to communicate with myself in poetry.

Gia: I’d love to talk about the final poems of Prescribee. The penultimate poem, “Let Me Lay Down Like a Song” references the Taiwanese activist Peter Huang and his attempted assassination of Chiang Ching-kuo. Following this, the final poem, “Go Back to Your Country,” subverts the title’s racist jibe by embracing the phrase (the poem begins, “which I would very much wish”) and ending with the speaker’s comically grotesque transformation into a white person. But I also notice there is a sense of coming full circle at the end of the book, which begins with poems about the speaker’s immigration to the US, and closes with this monstrous scene of assimilation. I would love to hear more about your thinking behind ending Prescribee with these two poems.

Chia-Lun: Whenever I think about Peter Huang’s story, a part of my soul sinks into the abyss. In order to pay my utmost respect, I let my voice weigh in and agree to disagree. I wonder when he shouted in English, “Let me stand up like a Taiwanese!” What does he imply?

There are times after I hear a story, the emotions stray and occupy my thoughts. Indeed the story is done, but my feelings still await like a ghost, that’s the moment when poetry comes in to validate and fondle this little lonely creature. When my first chapbook was completed, I didn’t know how to title it. I had no idea what my writing was about. Then I named it, “One Day We Become Whites.” Before coming to the US, without knowing too much or only learning from the media, I had the desire to be white, and I believe it’s because I hoped to save my family from our class and a possible war. But through the process, I realized perhaps I’m just a snob who wants to be superior and the distance growing between me and my family became unbearable. After naming my chapbook, I wrote “Go Back to Your Country,” an impossible wish to recover all of the lost years.

Prescribee is one journey from the first poem, “Parents,” beginning with a departure, to the last two poems, “Let Me Lay Down Like a Song” and “Go Back to Your Country,” ending with an arrival, as a citizen and a family member. The poems in between are tickets to memory, history, and the present, granting entrance to America, and tracing the erasure back to my home.

***

Chia-Lun Chang is the author of Prescribee (2022), winner of the Nightboat Poetry Prize, and two chapbooks, An Alien Well-Tamed (Belladonna*, 2022) and One Day We Become Whites (No, Dear, 2016). She has received support from Jerome Foundation, Vermont Studio Center, Tofte Lake Center, Poets House, and Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (Sarah Verdone Writing Award 2022, Governors Island Arts Center residency 2021; Process Space 2017) among others. Chia-Lun teaches contemporary Taiwanese poetry and fiction at the Brooklyn Public Library. Born and raised in New Taipei City, Taiwan, she lives in Brooklyn.