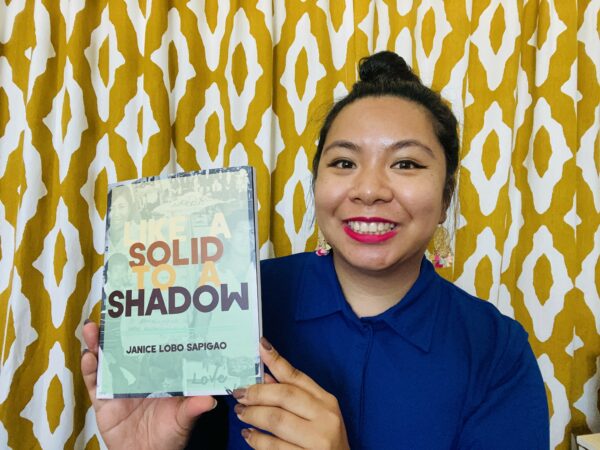

Janice Lobo Sapigao, Author of like a solid to a shadow, Speaks to Nightboat Fellow Snigdha Koirala

Happy pub day to Janice Lobo Sapigao’s like a solid to a shadow! Janice and Nightboat fellow Snigdha Koirala celebrate the reissue of her second collection by discussing translation, documentary poetics, and the various registers of language running through her book. Take a look below!

___________________________

Snigdha: like a solid to a shadow takes on the project of translating your father’s love letters to your mother in cassette form. And it involves you working with Ilokano—a language of which you have imperfect knowledge. What was this process of translating like? Did this limited knowledge of Ilokano trouble your relationship with language in general? Or open up a new understanding of language?

Janice: I learned (and am learning) Ilokano to learn more about my family and where I come from. I thought, when I started, that I’d get a concrete answer. I assumed, I realized after the fact, that the answer would come neatly, ordered, apparent. I know now, that learning another language to try to understand the silences and secrets in my family–of which there isn’t a language, in a way– would only bring a heft of further questions. The process was hard, solidified, dark. When I am learning Ilokano, I come into contact with how much I don’t know. I find what’s American, what’s English, and what feels unknowable (not sure if those are synonyms, but it feels like it, sometimes).

Yes, or can I say–hell yes, learning Ilokano has been an unlearning of English for me. It troubles me but also there is an excitement, a reclamation that I willingly engage, quit, and come back for. My partner jokes that I’m an Ilokano class drop-out (which is 100% true at this point), but I know I’ll be back to learning again soon.

Snigdha: Given that the book develops and engages with documentary poetics, there are various registers of language throughout. How did you navigate these registers throughout the writing processes? What kinds of tensions, frictions, or relationships did you find between them?

Janice: I like the word ‘registers’!! Does this imply music? Or recording? I hope so. I definitely navigated with a lot of sitting in silence and constantly asking myself, “What does this mean?” I’d look at a word differently by trying to rewrite it. For example, in the book, I have definitions of Ilokano words, vocabulary that I needed to help myself remember, like the word daytoy, which means “this one.” The short poem I wrote is a definition of the word, but it’s also attached to an image, story, or memory that helps me remember it, “this one / the sun around us / overcasts arrows at / mountains we forgot.” I tied the Ilokano word to a sun because, to me, the sun communicates time and points us to places. The word ‘day’ in English is in daytoy, which I wanted to break up and bring into the poem. Daytoy is pronounced die-toy, so then it left me thinking about the relationship between days and dying. My meditations on Ilokano became finding the English in it, which is strange because I am trying to tether myself to Ilokano and not English. That, in itself, is a tension, friction, and relationship that left me needing one to find the other.

Snigdha: Building on this, the book also has a visual element to it: maps, handwritten notes, messages, and emails. I was drawn to this almost typographic element that adds to the various registers of language. How did you approach the relationship between the visual and textual throughout the collection?

Janice: I took an intuitive approach to purposefully splicing the visuals and maps. I wanted to create a book of fragments, even though I think a linear or chronological narrative of my personal and family history and the collusion of secrets would be just as compelling. Books like Eleni Sikelianos’s Book of Jon, M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! and Hugo García Manríquez’s Anti-Humboldt: A Reading of the North American Free Trade Agreement / Anti-Humboldt: Una lectura del Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte are visual, political, and poetic in their usage of space and prosody inspired me to examine that relationship between the unheard-unseen (Ilokano, my father) and what I wanted to find and learn (Ilokano, my father). This exploration didn’t lead me to a circle of the same truths, but maybe to a circling. I also think I approached the text the way poet Patrick Rosal talks about how his work is in dialogue with history, “I’ve been visited. It’s almost as simple as that…There are certain poems I read aloud that invoke something I can feel, channel, and, to a certain extent, shape. That “something” is spirit or ancestor or the very specificities of history…”

Also, I just wanted to say: the handwriting in the book actually isn’t mine. It is Emji Spero’s! 🙂 Thankful for them for writing the notes, because in my original manuscript, they were typed, but I really like the handwritten effect that mirrors the effect of being a student and note-taking.

Snigdha: There’s also a spatial element to the book in the way you situate and place the poems on the page—sideways, upright, on the left, and on the right. You write that you “want the page to appear simple and to contain what is most important to [you]—which is the seemingly straightforward presentation of a text and the underlying tumultuous journey that undoes it.” What role does experimenting with space and page play in this undoing?

Janice: I think that playing with space allows readers to read through the book as I felt or handled the information I was given. On some pages, there are two short poems over the course of two pages, which allows readers to focus on what’s in front of them–text so alone, or left alone, or maybe even lonely. They are left with the blank or white space of their thoughts, or they have the space to keep on and move on. On other pages, the poems collide as you stated–sideways, upright, aligned left or right. I think this reflects how I received answers sometimes without warning or awareness of how heavy the information was going to be. For example, I didn’t know what my father’s voice would sound like, but it comes, and it’s full, and staccato, and spacious with its own silence. In addition, I didn’t know my family would have so much knowledge about things I’d wondered about my whole life, and at the same time, I guess I didn’t realize how much their knowing and my unknowing could feel like a cruelty I’d not expected. Overall, I think that experimenting with space leaves a lot of pages and stories for people to fill in, which is, I think, my exact experience of putting this book together.

***

JANICE LOBO SAPIGAO is a daughter of immigrants from the Philippines. She is the author of two books of poetry: microchips for millions (2016), and like a solid to a shadow (2017, second edition 2022). She was named one of the San Francisco Bay Area’s Women to Watch in 2017 by KQED Arts. She was a VONA/Voices Fellow and was awarded a Manuel G. Flores Prize, PAWA Scholarship to the Kundiman Poetry Retreat. She is an Associate Professor of English at Skyline College, the 2020-2021 Santa Clara County Poet Laureate, and a Poet Laureate Fellow with the Academy of American Poets.