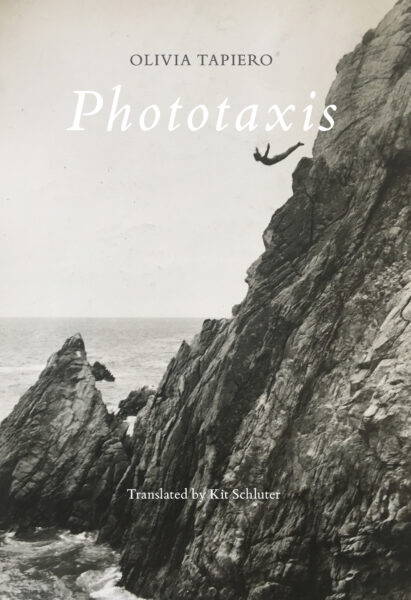

Today is the publication day of Olivia Tapiero‘s Phototaxis! In celebration of the book’s release, we’re excited to share a conversation with Tapiero and translator Kit Schluter about the poetics and music behind Phototaxis. Read on below!

Olivia Tapiero’s Phototaxis is a book of voices—voices chanting toward the rising light of a posthuman world. From the many, three voices arise as its heart: that of Théo, a classical piano player whose suicide lends the book its gravitational center; that of Zev, a political activist whose dogmatism, through contrast, draws into focus the book’s aspiration for discursive refusal; and that of Narr, a young woman from the “colonies” whose refusal to identify herself with seemingly any concept—let alone community—becomes emblematic of the book’s ethics of evasion. Through their absences in each other’s lives we come to know them, and along this path of absence the book develops its powerful song.

Like Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell, Nathanaël’s Carnet de somme, Danielle Collobert’s Dire 1 & 2, or Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee, Phototaxis is a work of the lushest interrogative bile. It spews its fragmentary lyricism all over the world it was composed against, scalding it, leaving behind the regenerative energy of wounds. And yet however anti-human this book may feel at times, its thrust isn’t in opposition to the human in general, but specifically to the West with its death-driven race to taxonomize, identify, and extract, at any cost, all possible capital from every detail of life. To say it more affirmatively, it could be said that the book was written in solidarity with all life, all possibilities—human or not—which that system has trampled, is currently trampling, and will continue to trample until it exhausts what’s left of its fuel. As a reader, and as a translator, Phototaxis left me wondering: what more inhabitable alternatives still remain for our world? And which has the West permanently destroyed along the way?

Three years ago, I almost drowned off the coast of Oaxaca. Eventually, a friend came and dragged me back in, slantwise over the riptide, but before his arrival, what struck me—what scared me (with a pervasive, heightless vertigo)—was how slow it was all going to be, how gradually I would be pulled out of life and into death, as if the threshold between the two were viscous, hungry for me and yet careful about what it was willing to let pass into itself. The apocalypse in Phototaxis reawakens that feeling inside me, but on a global, rather than an individual scale. It is the composition of our shockingly slow and voluptuous decline. —Kit Schluter

KS: Olivia, you open your book with the bombing of a museum, and proceed to craft a litany of memorable images: a city with sewers that are inexplicably overflowing with meat, the inner thoughts of a man addicted to watching YouTube videos in which people die, a classical musician struggling with feelings of mediocrity and self-aggrandizement, suicide by leaping from an apartment window, a cleaning girl at an old folks home masturbating behind the bedroom curtains while the residents lie asleep, the world slowly enduring environmental and economic collapse. You’ve said in another context that the main characters in Phototaxis—Théo, Zev, and Narr—speak in “counterpoint,” a term you borrow from music. Could you talk about the role of counterpoint in the characters, as well as in some of these images from the book?

OT: I feel like the different voices that are intertwined are composed in counterpoint, they carve each other out, through the interplay of blindspots, absence, friction. While Théo, the pianist, represents a Western collapse, the collapse of a certain type of performance, Zev stands for something like the greenwashing of white supremacy, the kind of rampant ecofascism that unfortunately populates apocalyptic discourses. They are both somewhat disciples of exposure—whether it be the clarity of doctrine, of images, or of self-representation. While they dance it out, another voice starts to take over, a third that reveals something about them, frames them in a larger collapse, that of ecosystems, which coincides with the rise of fascistic surveillance states. Narr hijacks the book halfway through, and something changes. It affects the language, the style, the rhythm, introduces a kind of resistant lyricism, something opaque, that dismantles the very structure of the book, which disintegrates along with it. Of course, this disruption was never planned. I imagine that it must not have been easy to translate… how do you translate an i(nte)llegible body?

KS: I could return the question and ask: how do you write one to begin with? One of the most exciting parts of translating your book was how Narr’s voice—the sentences of which compose the book’s philosophical spine—called for the end of systematic thought, dogma, clear allegiances, and itself formally dodged these certainties in the moments of her expression. An emblematic phrase: “I claim nothing as my own, am suspicious of solidarities, specificities from which it would be possible to extract decodable stakes.” The challenge, then, was to locate your ambiguities with precision, to recreate your vacuums of normative clarity very clearly—to translate both what your language was expressing and also what it was deliberately leaving out, omitting, refusing.

Another aspect of the book I cherished translating was its sense of humor. While the book may appear deadly serious on its surface, beneath that surface I frequently encountered a disarming irony, a spirit of play that lent your critique the humanity I think any critique requires to be actionable in a social milieu. Often the humor is quite dark, while other times your voices achieve what struck me as a slapstick of futility (the agent, the conductor, Narr’s mother and father). On that note, I’d like to quickly ask you your thoughts on the place of humor within the book.

OT: In Phototaxis the sense of humor is very much Bernhardian. It’s one of excess, contrast, disgust, theatrics. I feel like this reads differently according to contexts. My intuition is that Québec and the USA have different relationships to violence—where I write from, violence is never really avowed, whereas I feel like the USA conceptualizes itself as violent. So the violence in the context of this translation is perhaps less shocking, which allows for this dark humor to come out. Whereas in the initial reception, in French, the book was read as deeply dark, but not humorous at all – people were like “bitch, chill out, we’re suffocating in your text.” But the suffocation is part of the humor: it’s an over-the-topness that prolongs itself through the text’s surreal and lyrical aspects. I also feel like the text, written in 2016 and published in 2017, resonates more now, given the various crises that have appeared and/or worsened on a global scale. Maybe the book seems less alarmist in 2021, and more like a psychedelic mirror. Maybe prophetic things are only funny in retrospect.

KS: Speaking of which, I’m taken by your vision of lyricism, in particular how you use it as a form of opacity that can be utilized to resist simplified identification, to complicate and enrich the expression of selfhood. US writing, if I can speak generally, has an established and celebrated tradition of deriding lyricism for skirting the political—decades of academic disdain—but your work reconceptualizes this approach from other standpoints. In your work, lyricism and the lyric subject have been weaponized against the problems they are generally viewed as facilitating: idealized subjectivity, reduction of identity, transparent and capitalizable language. Narr’s lyricism pervades its themes like a noxious humidity, using its “profligacy” as a tool to accelerate the rot that she identifies as already lying within them.

One of my favorite aspects of being a translator is working with authors whose ideas challenge and offer alternatives to dominant trends in US writing. In the case of your work, two examples of this come to mind right away. First, I’m struck by how your language almost violently questions the very possibility of identity—in particular, at the moment of its enunciation. At times, it feels as if your vision of identity argues while it does define us and offer us a method for understanding our selves and histories, to equal measure it also throws us into categories whose derivations and definitions must be constantly reexamined if they are to serve us at all. (I think of genealogy.) I find this to be related to the second aspect of your work I’d like to underscore: the political motives behind your use of the lyrical voice. What are your thoughts on these themes and their relation, or lack thereof?

OT: I’m bothered, bored and othered by the devaluation of what is considered “lyricism.” The question of who can afford to be lyrical is tied to that of bodies and the space that they are allowed or forbidden to take. When white men are lyrical, we don’t say they’re lyrical, we say they’re ambitious. And of course this kind of freedom and “ambition” is not granted to all, it is not always legible as such, and is too often seen as clumsy artifice (and let’s keep in mind that under the critique of artifice there is always the critique of the feminine). The process by which a text will be categorized as “lyrical” is deeply gendered and racialized. Anti-lyrical aesthetics resonate with a logic of purification, a gutting of affect, of musicality, of what transcends the strictly verbal nature of writing and meaning.

I appreciate the (de)generative aspect of writing when it spills over some imagined border of a “correct” style, when we don’t fully control what is at hand. I try to welcome such spillings.

I was also recently thinking about how these various understandings of style correspond to different ways of approaching the non-human world. Perhaps we are starting to awaken from a deforestation of voice, an extractive relationship to language and meaning.

And I feel like these things are somewhat tied to the question of identity, naming and categorization. While delimiting identities, especially marginalized ones, is definitely a fertile temporary strategy in order to be visible and to weave communities, I also interrogate the underlying desire to be intelligible to unmarginalized eyes, a desire to be digestible—identifiable, that is consumable, marketable. Yet there is something powerful in the refusal to be fully seen (in this, Nathanaël has been an oblique teacher and a precious friend). There can be something wonderfully disruptive about resisting the temptation to translate oneself for the very worlds and languages that dispossess us.