Of Archives & Absences: Gillian Osborne, author of Green Green Green, on Orra White

Happy publication day to Gillian Osborne’s Green Green Green, a collection of hybrid essays on histories of nature writing and the natural world. Here, Gillian Osborne writes on the work of artist Orra White, the wife of American geologist Edward Hitchcock, and how the impact of her work and the experience of looking through her archive influenced Osborne’s thinking behind Green Green Green.

______________________________________________________________________

“When Flowers annually died and I was a child, I used to read Dr Hitchcock’s Book on the Flowers of North America,” Emily Dickinson wrote to Thomas Wentworth Higginson in 1877. “This comforted their Absence – assuring me they lived.” This fragment from a letter, a handful of words I read over and over, over years, became one of the seeds that became Green Green Green.

There’s so much happening in and around the “Absence” in Dickinson’s letter: repetitions of loss “comforted” by memory and imagination, a distance that could be recovered through attention, a lack as an invitation into further reading. Reading Dickinson led me to her “Dr Hitchcock”—the geologist-minister, Edward Hitchcock—whose sermons on the seasons led me to the work of his artist-naturalist wife, Orra White, whose images provide a counterpoint to much of his language: from almanacs, to lectures and textbooks.

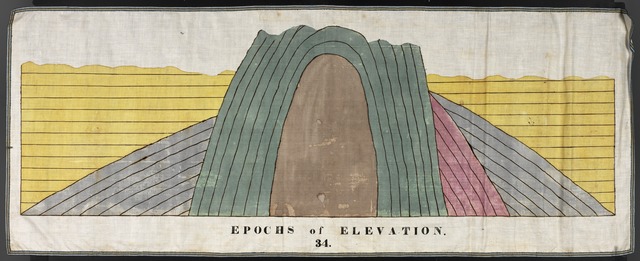

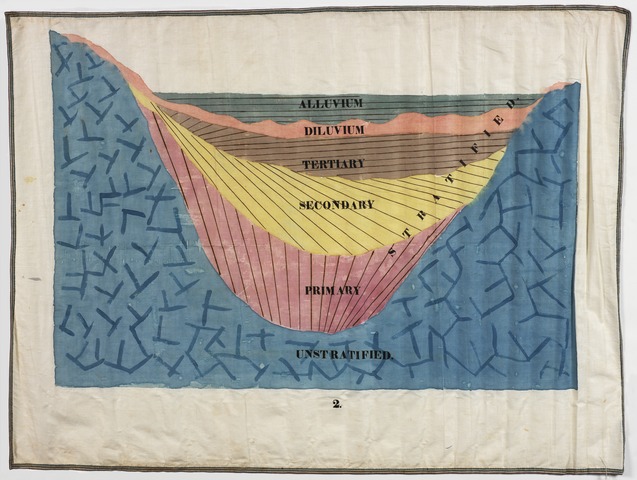

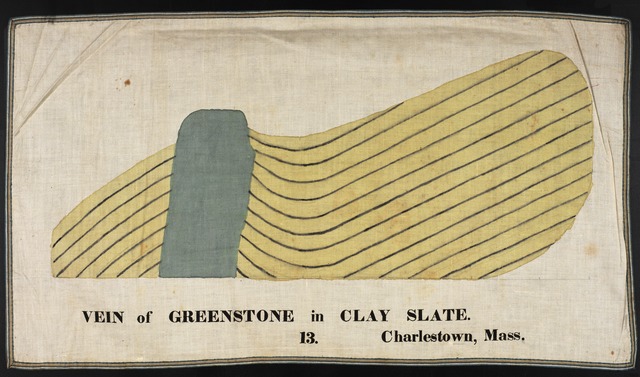

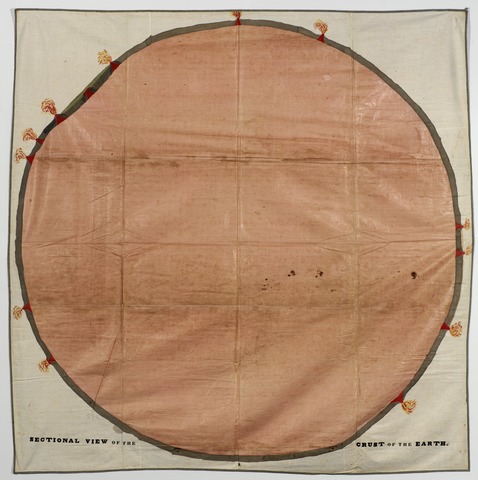

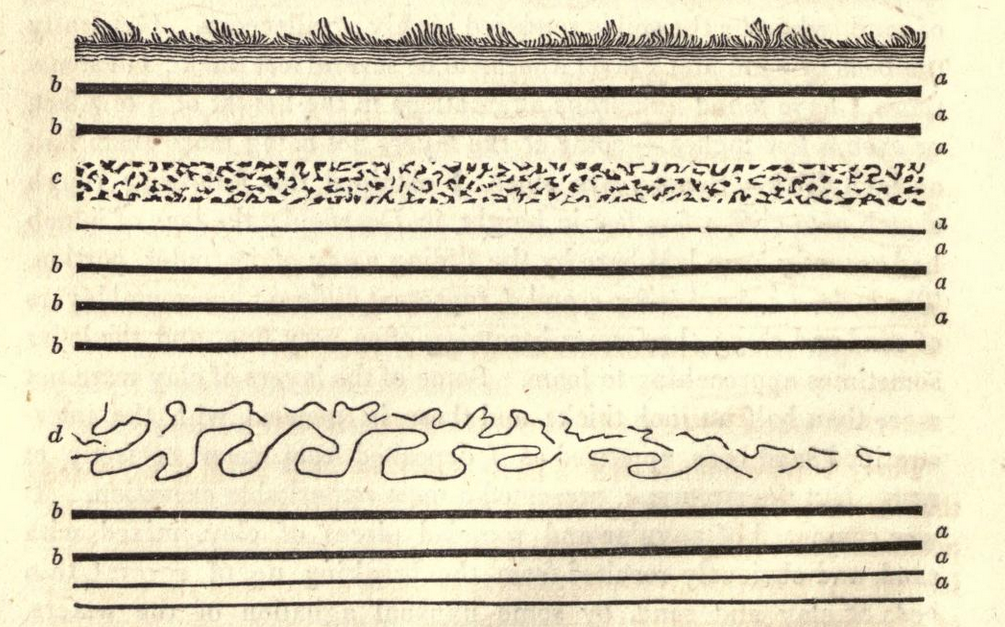

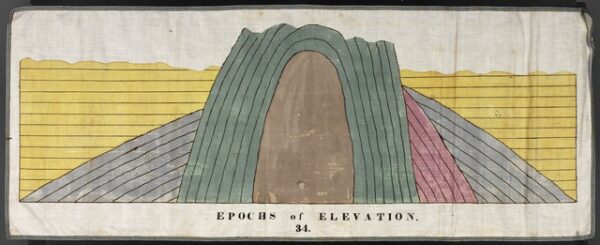

For me, the visual allure of Orra’s images is multivalent, and transhistorical: their grounding in materials, their shaping by historical and scientific knowledge, and their appealingly graphic flatness. These images are: literal depictions of geological phenomena—greenstone pushing vertically through ribbons of clay, epochs of stratification, a living planet peppered by volcanoes; also, the reflections of a historic understanding of geology (how close that magma is to the Earth’s skin); and, to a contemporary eye, illustrations of color, plane, and line. When I look at her depictions of soil structure, I see a diagrammatic rendering of depth underground, and a writing prompt: What would a poem, or an essay, look like, modeled on the pacing of those lines?

To borrow a term from Inger Christensen I’ve been circling around a lot lately, there’s an “interplay” between materials and imagination, the concrete and the abstract, in Orra White’s work—and in Dickinson’s—that’s also a correspondence between history and the here and now. When I read common names in Dickinson’s poems—all those basic, literary flowers—daisies, roses, lilies, etc—I know there’s an actual garden with a vaster array of species just beyond the scrim of those linguistic gestures. That the “Blue – uncertain – stumbling Buzz” of a “Fly” that suspends the moment when a poetic speaker dies is not only the abstraction of a color, or reverberating alliterative hum, but also Calliphora vicina or Calliphora vomitoria, the common Blue Bottle, which lays its eggs in corpses, a fact which allows forensic researchers to date the timing of a death.

All that makes history feel alive to me, an “Absence” thick and vibrating. In The Political Unconscious, Fredric Jameson memorably defines history as “an absent cause,” something gone missing that can only be apprehended through what gets left in its wake. In my writing practice, that conversation runs two ways, mediated by the continuity of non-human materials, which humans touch, but whose lives, and time-scales, differ from our own. Hitchcock found dinosaur prints on the banks of the Connecticut River. The hills around Amherst that Dickinson wrote of still surround the town, and will, long after the town is gone, in a green fold.

The way materials echo inside language also reminds me of what Susan Howe says in an interview published at the back of The Birth-Mark, that for women, “archives hold perpetual ironies. Because the gaps and silences are where you find yourself.” It’s not only gender that keeps voices, and bodies, out of archives. Not to mention all the plants and clouds and hills that nourished the lives a library never let in. Archives are sites of absence, partial records, intentional occlusions, irretrievable loss. A plant is a living thing we can touch and smell, a way of being with what was never recorded. I feel the presence of everything that doesn’t get written every time I sit down to write.

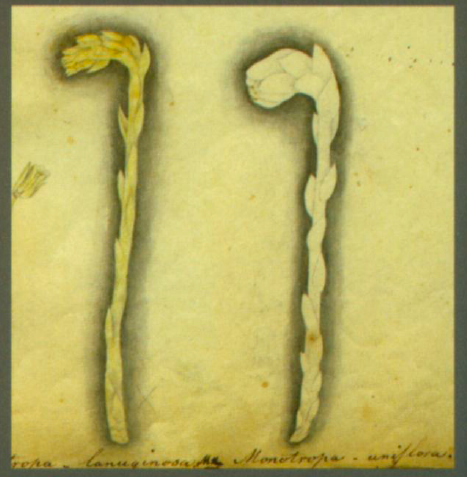

Before she made these geological classroom drawings, Orra White made another series of botanical illustrations: the insides of flowers splayed before a lecture-hall, pistols and stamen all out of proportion to their reticent scale. She didn’t like them, didn’t like, in general, working on a large scale. But I appreciate the usefulness, and the awkwardness, of her classroom drawings most of all her work. I hope those exaggerated flowers are still rolled up in a basement somewhere and that someday they’ll be found.

Until then, and maybe even then, I’ll read around them, which is something like imagining, and continues to be a comfort for “their Absence – assuring me they lived.”

- Classroom chart on linen drawn by Orra White Hitchcock, Amherst College.

- Classroom chart on linen drawn by Orra White Hitchcock, Amherst College.

- Classroom chart on linen drawn by Orra White Hitchcock, Amherst College.

- Classroom chart on linen drawn by Orra White Hitchcock, Amherst College.

References:

https://www.inaturalist.org/guide_taxa/370108