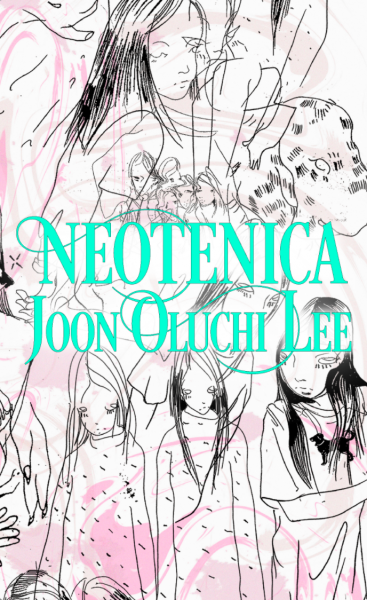

As Pride month approaches, we’re revisiting Neotenica by Joon Oluchi Lee, finalist for the Lambda Literary Award in Gay Fiction and the Ferro-Grumley Award for LGBTQ Fiction from the Publishing Triangle Lambda Literary Award! Editor (and fellow Nightboat author) Andrea-Abi Karam sits down to pick Joon’s brain on writing sex scenes, queer life in the early-2000s Bay Area, and the future of gay cruising post-pandemic. Take a look!

_______________________________________________________________________

Andrea Abi-Karam: As you already know, we both lived in the Bay Area but at slightly different times. Could you talk about the process of writing and setting Neotenica in an early 2000s Bay Area—an era that has been swept away dramatically due to the forces of gentrification and technocapitalism—and what were your motivations to revive this era in fiction? Did you find that your memory had been disturbed / mutated by time?

Joon Oluchi Lee: Well, I think the Bay Area, and San Francisco in particular has just mutated in the worst and depressing way by technocapitalism and unchecked gentrification. But I don’t think that my memory of the Bay Area has been disturbed or mutated by time—but it’s not like I have an idealized version, although I admit I’m very nostalgic about it. I lived in the Bay Area from 1997 to 2005—and I still have family over there. There was like a little loophole, a little crawlspace of time between 1997 and 2000 when there was still a lot of the “old” Bay Area left, which for me, was gay life: divey bars full of cruising people, big warehouse parties wherein you could see Cece Peniston or Jody Watley perform little sets, the Lexington (which one friend called “the baggage claim”), and even the Barbra Streisand Museum which was just like one narrow storefront on 18th and Castro, was still there. It was fucked up for all sorts of reasons, but it was a scene of my becoming a queer person. During those few years was right before the totalizing gentrification and technocapitalism you mentioned—I think the first tech bubble burst around 2002 or something—and so the Bay Area that is embedded in my brain is a timespace of transition that allowed queer people like me a vast playground to cut myself a body and psyche by coming into so many different kinds of gay people and contexts. It was a narrow timespace that is, like most narrow spaces, both confining, cozy, and uncomfortable.

AAK: I absolutely love the slipperiness of desire and sex in Neotenica, from Craigslist personals to laundromat encounters—given the last year of pandemic hyperisolation and escalating criminalization of sexual encounters in public space, what will the post-quarantine queer cruising scene be?

JOL: I shudder to think because I think that queer cruising had been long decimated by digital technology: Grindr basically sped up the heart of Craigslist personals by turning sexual encounters into a takeout delivery service…in that Seamless et al. are derivatives of gay hookup apps! But I don’t know, really…I feel like queer cruising is about the unexpected and the unknown. To me, it’s about the random guy in the library bathroom who winks at you from the adjacent urinal, or going to a bar and getting shitfaced with your pals and then hooking up with a guy you’d never think was cute, but who buys you a drink and then you learn that that is the kind of guy you find cute. The element of surprise is something that had been effectively eliminated from queer cruising. So post-quarantine…who knows?

AAK: Could you share with us your interest or obsession with the ideas underpinning neoteny? Did this interest arise from your academic/PhD work, or if not, from where?

JOL: Actually, the whole neoteny thing is not so much academic but personal, as a dog parent! When my partner and I first adopted our dog Nella—this was like six years ago—I did a lot of reading about dogs, both classic training books from people like Barbara Woodhouse and newfangled new-agey stuff (but NOT that awful Cesar Millan guy who advocates pack leadership crap) and more “academic” books on how dogs and humans became symbiotic. In one of these books, about the link between foxes and dogs, is where I encountered the word and idea of “neotenic,” which they described as unique to dogs in comparison to their canine ancestors or relatives: dogs retain traits of puppyhood into adulthood: proportionally big eyes, floppy ears, etc. I had just started writing the first few stories of what would become Neotenica and honestly I didn’t even connect the two at first. It was only a couple years later, when I had most of the thing written and was thinking about a title that I thought of it again because I realized what I’m interested in is the ways in which we as adults hold onto “baby” traits in a way that could be grotesque and cute. In dogs, it’s always cute, in humans, usually grotesque. I think about neoteny in terms of the psyche and how we perform ourselves in the world—how our “inner child” becomes a part of our external-facing selves.

AAK: What are the books, albums, celebrities, film, experiences etc. you drew from in the making of Neotenica?

JOL: So many! I actually think it’s important to read a lot of stuff before and as you’re writing. I know some people don’t like to do that because it might “contaminate” their voice but I actually like being contaminated. For Neotenica I was holding: The Sea Wall by Marguerite Duras, Last Splash by the Breeders, Dancing on My Grave, which is the autobiography of the great American ballet dancer Gelsey Kirkland, the art of Karen Kilimnik, the actress Anna Karina, and always, always, for everything I work on, Mary Gaitskill’s Two Girls, Fat and Thin and Sylvia Plath’s Ariel.

AAK: I am so impressed with the detail and immediacy of the eroticism and sex scenes in Neotenica. Can you talk a bit about the making of these scenes? How did you learn to write sex in these simultaneously explicit and artful ways?

JOL: Awww thank you. “Explicit and artful…” that is really the best compliment. I think about writing as vitally linked to the body—be it poetry or prose. Sentences, narratives, moods created by writing should tack onto your flesh like benevolent burrs. I will age myself here but when I came of age as a queer youth, gay porn was magazines, and those magazines contained not just pictures of hot guys but also stories—like literally short stories that were not just hot, like, masturbatory material but pedagogical: they taught me what sex between two males could be like, since no one taught me that, not at home, and certainly not at school, and not even on television, although everywhere one was bombarded with heterosexual sex and what the mechanics of that were like. So I think porn was kind of in my DNA when I was really beginning to take writing seriously and as a craft. It was like, I was writing a lot of tortured poems à la my heroine Plath but also jotting weird scenarios that I would find sexy. I just think sexual positions are the most marvelous scenes for written description.

AAK: What was your generative process like for writing Neotenica? Sustained bursts? Daily practice?

JOL: Ha, yes, sustained bursts. But also daily practice. In the beginning, it was bursts because I was like: what am I writing here? I had to just let whatever and whoever was in me creep out to figure out the people I wanted to write about, because for me, novels and stories are really biographies of a possible person. So stories or scenes or side characters would come, I’d have to figure out who was interesting, who was worth building a story around. Once I set up a “cast” then it was the daily grind. I really do believe in trying to write a certain amount a day when you’re working on something, even if it’s just crap, or even if it’s just one sentence. So for me, sitting with my fingers on the keyboard for a few hours every day is important.

AAK: What advice would you give to someone just starting to work on a queer novel project?

JOL: I would say—always try remember to think outside yourself. Whatever cultural or political advances we have made or are making, as a people, queer people are always going to be outliers in a society organized around heterosexuality. I think telling your story as your own unique person is important, but to always think about how it’s going to build onto the layers of what queer identity will mean for others, that others will use your text to craft their own selves to fight against heteronormativity.