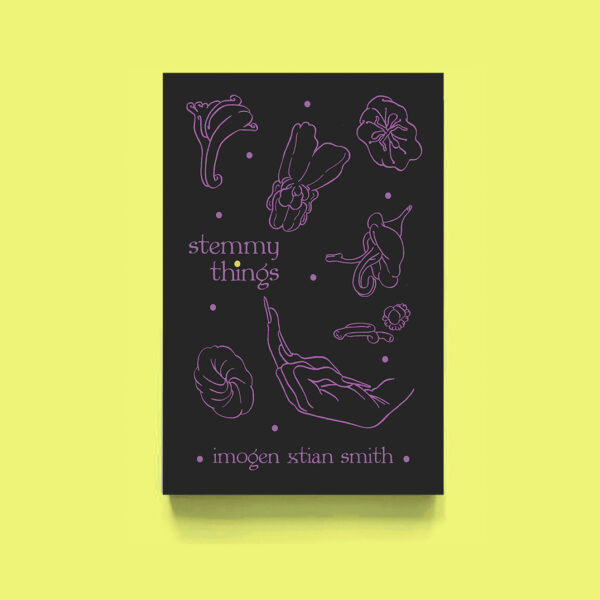

Interview with imogen xtian smith, author of stemmy things!

Girl-thems rejoice! The publication day for imogen xtian smith’s stemmy things has arrived. To celebrate, poet & past Nightboat Intern Ryan Cook speaks with imogen about communal spaces, SOPHIE, being “hot for long ass poems”, and more. Take a look below!

_________________________

Ryan: First off, I wanted to thank you so much for creating this book and answering some questions about it. As a trans person myself, I really found that the language and themes resonated with me. I particularly loved the colloquialisms, puns, and jargon that weave themselves within the poems in this collection. “Wild geese with transexuals & acid” comes to mind as a great example of this. I know some poets like to see each poem in a vacuum—what was it like to invoke all of these references and phrases to make an urban pastoral?

imogen: Hi Ryan—that is so sweet, thank you! i’m glad the book is landing w you.

i’m really disinterested in the idea of discrete poems, if they’re made to stand alone. Clearly, there are poems in stemmy things that fit this description, & you can always pull poems from wherever you are in process / project that illustrate what you’re working on, but i’m sort of annoyed by the way, say, magazine real estate necessitates a form in itself—that form being poem as discrete, digestible, legible & sellable object. i’m hot for long ass poems, durational pieces, concrete poems, sequences, journals, lists, epistles, things that aren’t easily containable. This could be a kind of trans poetics, but also, i just enjoy play.

i think in terms of projects, so the poems emerge from a sort of body i’m carefully constructing in conversation w itself & the circumstances from which it emerges.

Another way of responding is that i often think, if a line is good enough for one poem, it’s good enough for another! Like, if something really resonates, if there’s a thread, why not? My poems are trying to be useful in orbiting the questions i’m asking before offering what i find—to be taken or left or whatever, & maybe, along the way, multiple poems get at the same or similar strands of thought / desire / obsession.

A book holds its author’s language at the time of composition. As far as colloquialisms go, i use the language that’s coming from me & from around me—on the streets, online, text messages, in conversations & culture, in reference to other artists, etc. All that might shift in the next book, or absolutely will. It’s important for me that the work be trackable to any number of contexts, communities, times, spaces, places, & that the work be immediately dated by its language. i like art that’s really specific & this is a question of ethics. The universal strikes me as unethical.

All this renders the work more alive. i was transcribing my journal earlier, & a phrase jumped out that i was happy to remember thinking—a book arises from within communal space. This probably came on the heels of talking w Becca Teich. At any rate, this “make your poem universal, don’t be too specific & date yourself” kind of thing is hollow to me & my work. Like, tell me what’s at stake for you? That helps the poem find a place w / in larger ecologies.

P.S.: i love that you used the phrase “urban pastoral,” because the book (& especially true blue uncanny valley), is very much going for that.

I would love for you to talk a bit about the processes of deciding the sections and their journeys. What made you want to separate the book into sections, and how did you choose who to reference in the epigraphs? My favorite section, “true blue uncanny valley”— which is the section length poem in the middle of your book. That entire piece blew me away, and I wanted to hear about how that piece came about.

My writing process is really different now than it was when making stemmy things. There are moves in the book that are kind of from the MFA playbook, which is something i generally dislike & have shaken off, though remnants remain. Quite honestly, i was taught that that’s how you organize a book of poems, in sections. So i did, which was right for this project, but doesn’t happen in my new manuscript, weird connections.

i knew “true blue uncanny valley” needed its own section, for example, & wanted to begin in a sort of ecological place—to understand the eco-systems from which the person writing these poems emerged. So in the first section, you have nature poems that give way into questions of ancestry, nuclear family, suburbia, as well as Appalachia, all points along this very nonlinear process of forging a working understanding of becoming, moving from a night on LSD back through generations of both dna & artists into something like infinity’s dirt.

The “field jar” section is more observational—cities, the academy, my apartment in the early parts of the pandemic. It’s just a term i loved & that fit, borrowed from Andrea Rexillius’ work & like, my memories of catching lightning bugs in jars. Things to look really closely at, maybe some of them to scrapbook. All the dumb sexy poems didn’t really fit there, so they got their own section, which i wanted to be like a pop record, & really flirtatious. A lot of aspirational work there, as i move through queer embodiments. The last section is all gravity.

Re epigraphs—some i knew in advance (the Zora Neale Hurston for example…i feel such a connection between that statement & what “ecologies” is working towards). Others came along the way. i so often experience a synchronicity between whatever i’m reading & whatever else i’m doing. So maybe i was working on structuring the book, & also reading something that was blowing my mind & seemed relevant to how the content is organized.

“true blue uncanny valley” is my attempt at rendering both an urban pastoral & an ars poetica, on a spacious scale. i kept collecting fragments or repurposing good parts from other poems to sew together. Ultimately, you could read this section / poem & get the entire project of the book—maybe not the nuances, but the purpose—which is how a self or selves congeal durationally over the courses of lineages, artists, works, & importantly, social histories.

So yeah, this poem was an idea that lived w me, a kind of repository. i understood it’s why before it existed.

Also, i wanted to name the book true blue uncanny valley, but literally everyone i ran that by was like “no imogen.” But i love it as a title, & it suites the piece, in that while what we see on the surface may be materially accurate, the whole(s) that make up realities are incapable of total capture. Like, these are some things i see & that feel real, but also, i make no claim of understanding them outside whatever narratives or thought streams i produce, all defined by the contexts in which i have & do live.

Your willingness to sing the praises of other poets and poems allows for this work to not just act as a stand alone piece, but an ecosystem of wonderful minds. What works/authors would you want to put your work in context with?

Yes, the book is absolutely an ecosystem (but is not a project in ecopoetry!!!)! That’s why it’s so jam packed! i couldn’t conceive, during the making of it, any part working without the other. Looking at it now, it feels unwieldy, a bit overgrown, but that’s what happens, ecosystems being inherently queer & all.

It’s hard to say what works / authors i’d want stemmy things to be in context w, largely because i’m no longer making it, you know? & w my new work, it’s in conversation w a completely different set of artists & thinkers. Lots of poets are woven into the work though—it’s as much about poetry community & lineage as it is anything else.

W that said, i am majorly indebted to the life & work of Bernadette Mayer, her attentiveness to materiality, labor, the mundane, the small details of things happening in the world around you that actually shape the conditions in which you exist. Lots of poems mimic her in form (at least visually), & sometimes even in voice. i’d also like to think the work is in conversation w writers like Adjua Gargi Nzinga Greaves & Cody-Rose Clevidence, in terms of trying to represent ways of approaching deep ecologies, human & non.

In another sense, the lasting influence of Sarah Schulman’s The Gentrification of the Mind is huge, a big ethical impetus on my “urban pastoral” projects. i wouldn’t dare put stemmy things in a window next to Audre Lorde, but so much thought about what writing can be good for, how it can be useful, & the risks involved in trying to tell the truth of living in this society as whoever you are, is informed by her work.

In general though, i’m a big fangirl of so many friends & peers & ghosts.

Speaking of ecosystems, your use of ecological images in the poem is so hot; things harden, mature, leaves and stems bare themselves in the process of change. How has your relationship to nature changed throughout your life?

i don’t think it’s changed much, really. i love being in the world, which is always nature, right? i mean, it takes different forms—the city is nature, as opposed to mountains or something. i can’t walk out my door straight into some woods—that was a different life. i crush hard though for plants coming up through the concrete, or fences. “Weeds.” Totally hot.

But in terms of a specific usage of that word, i think that looking at non-human beings helps me make sense of what’s happening to me, whatever i’m going through. Take being trans for example—there’s so much i can literally step outside & immediately see that renders that positionality quite sensible, since nothing is fully adhering to taxological boxes. If there’s something trans about a plant or bug or other mammal, it seems reasonable to think that the processes at work there can’t be dissimilar to whatever’s going on w my body. Things are really complex, but also, somehow, not? That might sound hippy AF, but seems logical to me, & places me within an ecosystem, not just a being human in opposition to everything.

You use a variety of forms in the book, and I wanted to hear about your relationship to form in general. Do you find a certain affinity to one type of form or syntactical element?

The poem reveals the form it needs to take over time. It teaches you how to write it. i’m pretty ignorant when it comes to Form, although i think a volta is a really hot concept. Sometimes you notice that couplets or tercets make a poem feel more navigable, so there’s that. The syntax of stemmy things is excessive & melodic, & i def love an em dash & take it to mean what i take it to mean in Emily Dickinson’s poems—queer longing, just hanging there. i also love to leave a thought unfinished, to just drop off. Like, if i don’t know the answer, the poem surely doesn’t, & how to best represent that unknowing?

The first time I read your work I felt as if someone was peering right into my thoughts about my body. Has your work changed alongside your discoveries with gender, and what types of poems helped you along your journey with gender?

Hard to answer, because the poems are not separate from my body. i didn’t want stemmy things to be the characteristic trans memoir type deal, but in a lot of ways it is. Which feels good to have over w! Like, now i can write about literally anything else. Gender is always gonna be there, like it is in every human’s work & expression(s), but i don’t wanna be a “trans poet” that writes about “trans stuff” exclusively. Like, i have other interests, you know? Sure, transsexuality is a major part of my lens, my whole being, but i don’t necessarily want the work to be reduced to or caught up exclusively in that.

Early on though, it was Kate Bornstein & Leslie Feinberg, Kathy Acker & Kai Cheng Thom. Nevada. Anything Metonymy Press. MUCUS IN MY PINEAL GLAND. McKenzie Wark’s Reverse Cowgirl definitely gave me courage to write about sex, & it was in my orbit during the early part of the pandemic, when a lot of stemmy things came together. Aeon Ginsberg’s Grey Hound & Tel Aviv by Mohammad Zenia, too. All things Anaïs Duplan. Of course, i often go to both of Nightboat’s Trans anthologies.

i read lots & lots of trans poets, & plenty of other work also helped me along the way. Mayer’s “The Way to Keep Going in Antarctica” is perennially useful to me. Like it is yearningly painful-in-its-sincerity kinda helpful to me! “Nothing outside can cure you but everything’s outside” C’MON. Di Prima’s “Revolutionary Letter #1” is another. Everything June Jordan & Trish Salah—particularly “Wanting in Arabic.” Etel Adnan is a holy place. Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit is a workbook of play that’s wildly accessible to whoever you are at any given moment.

Not a lot of this specifically relates to my gender journeys, so perhaps the answer is disappointing. But the thing is, when you’re really working on yourself, it can be super helpful to lean into difference, see how ppl unlike you get over, you know? Bring back some of the spirit, if not always the contexts. Pay attention to the world & the fact of other ppl. i go to trans work for commiseration, to feel less alone, really. Tales & goss too. For illumination that’s really personal, but that i can also just keep between me & my ppl.

For you personally, how do you know when a poem is done? What is your editing process like?

i am RIGOROUS AF. Editing is really the art, the finished object is just, like, a photograph of all the emotion & labor that went into making sense of whatever you’re obsessing over. i do a lot of editing aloud, because i want the poem be intentional & interesting both on & off the page. So there’s a large sonic element, as well as a lot of concern for wordplay, line breaks, stuff like that.

IDK when a poem is done—if i could have a pass today at stemmy things right now, it’d be a different book. But that would squash its authenticity, right? It’s an artifact. i do know that i don’t think a poem needs to be perfect or polished or to do EVERYTHING. Like, it can just be a sketch positioned in relation to other sketches (back to your first question). Terrance Hayes once said to me “a poem just needs to be more good than bad,” & lol, that’s kinda the best advice ever! A poem doesn’t need to change the world—it can just be as it is, then moving right along…

i do def edit while giving a reading, so in terms of being done WITH a poem—if i’m still finding new ways to improv w / in it in the space of performance, then it’s still interesting to me. If the only way to present it is just to present it straight from the page, ad nauseum, it’s time to leave said poem to rest.

So i guess i’m very contradictory, in that i’m hyper meticulous & very into craft & P R O C E S S, but am also, like, “it’s just a poem you know.”

SOPHIE is mentioned MULTIPLE TIMES and it totally tracks — do you have a favorite song of hers?

Nothing definitive, but i really love “MSMSMSM” & “Pretending.” Also SOPHIE’s later, more long form & absolutely bass-squelching jams, where the low end can almost scare you & also make you cum everywhere.

Can you talk a bit about the choice to include an author’s note in the beginning?

That felt important, given the nature of the work. i engage a lot of things involving not only gender, but race, class, inheritances of many sorts, & i couldn’t imagine not prefacing that by saying “look, this is who i am & where i’m perceiving from.” That’s to take care of readers, to stay accountable to myself, & to ground the work. Civic. i’m not interested in assumed we’s or communities, am just as much a part this disastrous racist capitalist system of organization we live within as anybody (& that’s also specific). There is no universal place from which to write an “urban pastoral.” i felt that, sans the note, the work could feel very voyeuristic. Instead, i wanted to state from the jump who i am & where i’m calling from, so anybody can do w that as they may—whether it be relate to it, critique it, glean some perspective, or stay away from it in general.

Difference is really important & can’t be neatly reconciled, which, again, is why context is so crucial. In the end, i hope that the pieces in stemmy things emerge from a place of deep attentiveness & listening to + w multiplicities. The words are my witness, but the language has its histories while being so personal, so rooted in the specific materiality of my life. This makes any attempt to witness & reflect necessarily always suspect.