Brian Teare’s new collection Doomstead Days figures itself an oblong baritone shape, a cargo ship of poems and various other fuels barrelling towards us. Opening with the clamor of a container ship’s collision into the San Francisco Bay Bridge and the subsequent fallout, the book is as much witness and chronicle as it is elegy. In anticipation of his poignant new collection, Brian and I cyber-chatted about the Anthropocene, ecofeminism, elastic syntax, astrology, and more.

—June Shanahan

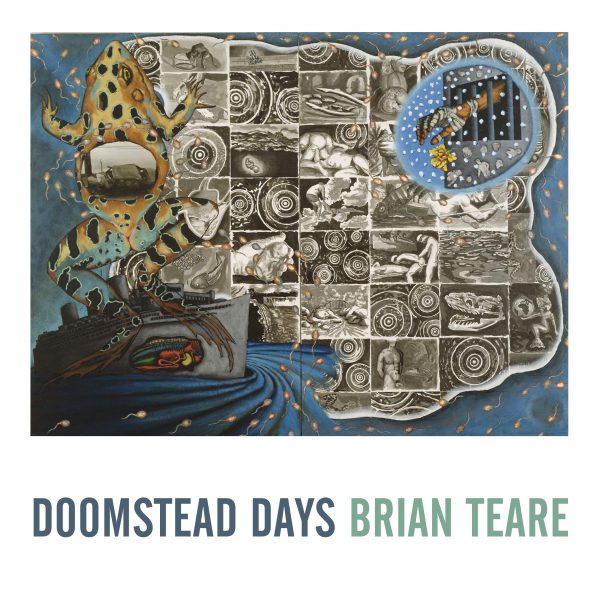

June Shanahan: In considering the cover art for Doomstead Days, I found myself thinking about the frog– how the slimy, webbed, amphibian might be a model for the future of global species faced with otherwise catastrophic sea-level rise– while also realizing that the amphibian, straddling biomes, might be uniquely vulnerable to the pervasive poisons of both air and water in the Anthropocene. I’d love to hear what you thought about when selecting this David Wojnarowicz piece for the cover. What is your relationship with his work?

Brian Teare: Wojnarowicz’s 1991 essay collection Close to the Knives and the catalogue for his controversial 1990 retrospective at Illinois State, Tongues of Flame, were formative for me as a young rural queer coming out and coming of age during the early ’90s. His work was my introduction to Act Up specifically and to AIDS politics generally, and his unapologetic, unashamed sexuality was an inspiration. His rage, his righteousness, his intelligence, and his tenderness, his humor – his visionary and unwavering criticality during crisis, his autodidactic resistance to institutions and aesthetic norms, and his style of being unabashedly queer – have always moved me. “Water” is part of a quartet of late paintings inspired by the classical elements of western culture. I chose it not only because of its beauty, but also because it encapsulates a lot of the themes of Doomstead Days. Like much of his later work, the painting offers an image-system that’s also a cosmology in which the watery fundamentals of life fuse with industry. Wojnarowicz uses insets to show the hybridity of life in the Anthropocene: there’s a crashed car inside the frog, and viscera inside the tanker, suggesting we can’t separate the natural and the man-made, or separate life from disaster. (The frog also made me think of the sixth extinction underway, and especially the Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis fungus that’s threatening to wipe out many amphibian species.) I love how the sperm-like tadpoles, or tadpole-like sperm, insinuate their fertility everywhere. And the liquid in the middle – is it a puddle of water or cum? or is it a magnified drop of water ? – contains images juxtaposing gay sex, fossils, cell biology, heterosexual reproduction, and suggests a long view of life on earth, which would have been, and would be, impossible without water.

JS: Many of your poems in this collection are based in movement through natural spaces, and you seem careful not to elide the resulting wear on your sometimes already-worn body. How much of your writing practice for these pieces relied on physical momentum and wear? Was that practice unique to this project or is it something you regularly engage?

BT: Except for the two sitting meditations, the entire book was drafted on foot between 2007 and 2017, which means a lot of time passed between some of the first drafts and their revisions. I’ve experimented with writing on foot since 2003, but the experiment gained focus and purpose during the composition of Companion Grasses (Omnidawn, 2013). I’ve written elsewhere at length about my en plain air practice, so I won’t detail that again here. But I would like to answer the aspect of this question that’s implicitly about writing while walking while chronically ill. I drafted early versions of the book’s first three poems during years when I was also writing The Empty Form Goes All the Way to Heaven (Ahsahta, 2015), which deals explicitly with chronic illness and disability, and was mostly composed in bed. The result is that writing about illness and disability got channeled into that book, while the drafts of “Clear Water Renga,” “Headlands Quadrats,” and “Toxics Release Inventory” focused on bioregional, natural history, and industrial use research, among other subjects I was interested in while upright and able to walk. Once I finished The Empty Form, however, I confronted the fact that even the newer walking poems tended to efface my physical struggles with walking, something that my friend, the poet Susan Tichy, also noted. Given the ableist ideologies that much environmental writing has implicitly depended on, and given my own unwitting participation in those ideologies, I vowed to her and to myself that my new drafts would acknowledge the days when walking is difficult, and to be honest about the impact and import of that difficulty. Returning to the drafts I had, though, I wasn’t always sure how to balance that acknowledgment with the more outward emphasis of the en plein air practice. The two sitting meditation poems allowed me more space to do that work, and then in “Olivine, Quartz, Granite, Carnelian” and “Doomstead Days” (and a late revision of “Toxics Release Inventory”) I was able to more fully integrate physical struggle into the walking meditation of the poem.

JS: Often in lieu of periods, you deploy double-colons – “::” – between sentiments. They create this really tight geometrical relief as well as a kind of series of magnetic points that seem to hold your forms together from various centers. I’m curious as to the significance of that choice, what made these markers feel most fitting or apropos?

BT: I love your descriptions of the work that the double-colon does, holding “forms together from various centers” : : YES : : I love the way that extending a sentence beyond its grammatical conclusion and yoking independent clauses through a sign of a kind of equivalency begins to decenter subjects and allow the complex relations between multiple actors and actions to become visible as a sort of network : : “a kind of series of magnetic points,” as you so beautifully phrase it : : plus the double-colons are a double literary homage : : first to A. R. Ammons’s habitual use of the single colon, particularly as it plays out in Garbage, where the emphasis is on an elastic material ongoingness rather than on a rigid finality : : and second to Alice Fulton’s use of ==, which she calls a “bride sign” : : “hinging/one phrase to the next” but “without dilapidating/ mystery” : : both of these writers know that a kind of consensus relation to reality is encoded in literacy and literacy’s relation to conventional grammar, and I like the way they use small tools like punctuation to begin the work of re-orienting the reader to reality : : I think punctuation is a particularly great place to begin this re-orienting work, given that it’s a small formal gesture that’s easily legible, even if its new meanings take time to suss out : : many of my poems re-orient the reader towards the real rather radically, and my hope is that to begin this work on the micro-level of punctuation makes that macro-level work more accessible : :

JS: The dichotomy between “the real” and “nature” comes up frequently in your initial poems. I’m interested in the way you posit nature’s inability to resist absorbing and distributing the toxins that will cause its own demise, the “invasive flammable” way of that which is left behind by the “real” (i.e. an oil tanker dumping its namesake, the downed power-line’s resulting fire and displacement, the coyote leaving innumerable piles of scat in its wake, etc., all absorbed and disseminated). What do you imagine your surrounding “biome” absorbs most frequently from your personal “real”? Is it the kind of detritus you’d hope for?

BT: I’m not sure I’d agree that there’s a dichotomy between “the real” and “nature” in these poems. In fact, I’d argue that the natural world is the largest and most fundamental part of the real, but that humankind – industrial humankind in particular – tends to treat it as a background to, and not the actual fabric of, the real. As ecofeminist Val Plumwood argues, the patriarchal master model of the real foregrounds culture, progress, and profit, etc. While relegating everything else to background “natural” resource. Which is why we’ve moved species around the world without thinking about the implications of those acts for either the species themselves or the ecosystems into which we introduce them, and why we routinely allow industries to drill in and ship oil through critical habitats despite our knowing how often oil spills happen, how devastating they are for resident species and water quality, and how impossible they are to clean up. But you’re right that the first draft of “Clear Water Renga” was written out of the emotions that arose as I watched the aftermath of the Cosco Busan wreck play out in the San Francisco Bay – the feelings of anger, sorrow, and impotence as I witnessed the real helplessly absorb the spilled oil and distribute its toxins throughout the Bay before coating nearby Northern California coast. Watching volunteers scrub a struggling grebe’s oiled feathers with a toothbrush, I viscerally realized the real can’t refuse what we put in it. That’s the basis of ethical relation: because the real can’t refuse, there is no such thing as being too careful about what we put into it. And to answer your final question: I don’t own a car, I walk and use public transit, I recycle and compost, I try to buy and eat food from within my foodshed, I avoid single-use plastics and packaging, I’m careful about my consumer choices, and I know these choices are personally meaningful but very potentially useless gestures of resistance. Like anyone else in the first world, I am always already polluted and polluting – even when I’m trying to offset that fact.

JS: A queer eros comes forth throughout the book, particularly in the final titular track, “Doomstead Days,” alongside an unrelenting migraine. I wonder, as you braid erotics and gender with collapse and world’s end, if you might find something particularly queer about the end of the world? Where do you think the queer erotic might be located in the anthropocene?

BT: As a queer ecofeminist, I’d have to say the end of the world looks very straight, very male, and very white. Along with Plumwood and other feminist ecological philosophers, I believe patriarchal culture constructs a fictional version of the real that ensures forms of dominance that shore up gender, race, class, sexual, and species privileges. There’s a reason the title poem critiques doomstead men:

“doomstead men live

doomstead days already

sealed in extreme fiction

as if there were

ever a way to stay

safely self-contained”

As those of us who are not, never have been, and never will be safely self-contained well know, the fiction of being able to control one’s own boundaries is one the privileged enjoy. And even then it is still a chosen fiction maintained at great cost to everyone and everything else. Just look at Trump and those who love him and his Wall: the privileged attempt to construct the real as a figurative doomstead, sealed off and defended from the real everyone else shares. Such a doomstead is a philosophical, political, environmental, and moral obscenity, particularly given that the privileged have spent the larger part of history violently subjecting others to their privilege. For instance: new research into the stratigraphic record suggests we could date the start of the Anthropocene to European contact with indigenous people in the Americas. Scientists speculate that the spread of diseases initiated by that contact wiped out so many people that trees they normally cleared to facilitate farming and hunting instead grew; this growth sunk so much carbon that it triggered the Little Ice Age that cooled the globe until the Industrial Revolution began to warm things up again.

At the same time, I’m aware that queerness as I understand it is a result of the sexual sciences of the nineteenth century, and that my sense of myself as a gay man and my sexual experiences are coextensive with the capitalist industrial culture into which I was born and raised. To be queer today is to be very much of the Anthropocene, though first world queerness is a really particular iteration of Anthropocene being, and is of course very different for a white cis gay man and a black trans woman. Which is why I think the Anthropocene (as an environmental humanities concept, not a scientific term) is kind of like a gender : : we all perform it in these large and small ways, from sex act to lip gloss, from public transit to bird-watching : : I locate the Anthropocene’s queer erotic in taking down the boundaries between the human political and the real, in acknowledging embodiment as relational and in relation to everything’s body, not just the bodies included within the human political : : I locate the Anthropocene’s queer erotic in “this/totally elastic/ materiality/I feel as ecstatic/ wide dilation,” and also in the fact that “all of my fluids” are “pollutants cycling/back into my own/ watershed toxins/& heavy metals” : : I locate the Anthropocene’s queer erotic:

“in the way the word

gender remembers

it once meant to fuck

beget or give birth

sibling to generate

& engender all

fertile at the root

& continuous

as falling water”

JS: Finally, and maybe most importantly, what’s your sign?

BT: It will surprise no one, given the last answer, that my rising and sun signs are in Scorpio. My moon is in Sagittarius. +

Doomstead Days is out now, order here!

A former Pew Fellow in the Arts, Brian Teare is the recipient of poetry fellowships from the NEA, the MacDowell Colony, the American Antiquarian Society, the Fund for Poetry, the Vermont Studio Center, and the Headlands Center for the Arts. He is the author of The Room Where I Was Born, Pleasure, Sight Map, Companion Grasses, The Empty Form Goes All the Way to Heaven, and Doomstead Days. Winner of the Brittingham Prize and the Thom Gunn and Lambda Literary Awards, his work has also been a finalist for the Kingsley Tufts Award. After over a decade of teaching and writing in the San Francisco Bay Area, he is now an Associate Professor at Temple University, and lives in South Philadelphia, where he makes books by hand for his micropress, Albion Books.

—

The new Nightboat Books blog will feature interviews, essays, playlists, reading lists and more super savory content to pair with our releases! Check back in the coming weeks for more from our exciting April poets!