Today on the Nightboat blog, we’re taking a spotlight to Cole Swensen’s Art in Time, published in May by Nightboat. Read through for Cole’s take on the artists who inspired the writing of this collection–as well as excerpts from the poems in Art in Time which resulted from her engagement with their work.

(We have attempted to keep the formatting of the poems as true to the book as possible, but our website has formatting limitations–please keep this in mind!)

Agnes Varda (1928-2019) was a marvelously pioneering woman in the world of film and is considered by many to be the founder of French New Wave Cinema in the 1950s, though others link her with the earlier Left Bank movement, which included Chris Marker, Marguerite Duras, and others. A vibrant, strident character with a lively sense of humor, she used her work to advocate for those on the social and economic margins. She was one of those powerhouse people who get stronger and stronger with age; she continued making films and branched out into installation art in her later years, remaining fully active until she died at the age of ninety. And while landscape was never, according to her own statements, her principal theme, it is so dazzlingly present in the background—so dazzlingly so that the background ceases to be background in the usual sense of the term. Her use of background shows us that it is, in fact, always a principal actor in every scene, whether it’s in a movie or in our daily experiences; it always constructs and determines our possibilities. She once said in an interview: “If we opened people up, we’d find landscapes.”

from “Agnes Varda: Here There & Then Now”

Landscape of sand dunes

the sun cut into seagulls.

Landscape in the shape of a breeze.

Breeze in the shape of its trees.

She’d originally planned a career as a museum curator but got intrigued with photography when taking a night class. Though soon found, she said, too much silence in photos and not enough time. Film as light in flight in time. She’d only seen a handful of films in her life when she made her first one, which she says she made by hand.

Landscape of evening

shadowing a park

Landscape of ventriloquist in nearby pavilion,

the land itself a voice

and the voice repeating:

My treasure

was a cedar. Landscape

of heart in water

of white shirts in a stream

of silence coming through a white sheet thrown over a chair—

Landscape of a sheet of sun made of bees.

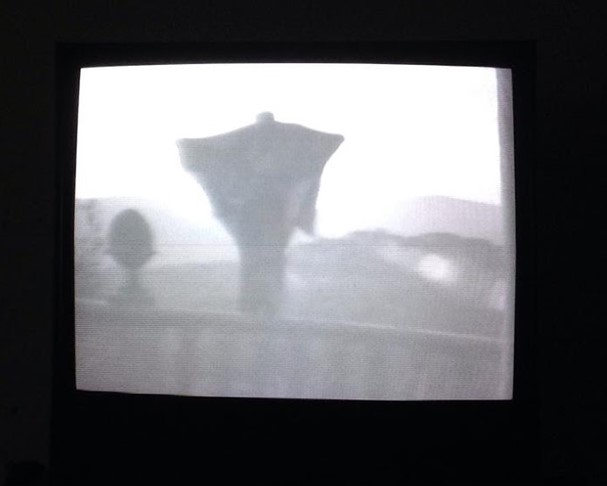

Joan Jonas (b. 1936) was one of the first artists to recognize the potential of performance as a medium and, in particular, to recognize the ways in which video and other emerging media could play a part. Active in the volatile art world of New York in the 60s and 70s, she has continued to pursue her own work while also engaging in collaborations with artists in dance, film, and theater. She had a major retrospective at the Tate Modern in 2018, which is where I encountered this piece, which blends choreography and soundscape within the almost tangibly-granular medium of early video. I was interested in the way that various low-production values—b&w, blurring, gravelly audio—all came together into an unusually graceful work, which made me think that perhaps grace is always a confluence of awkwardnesses—that smooth surety can never attain the graceful—and that only grace achieved by negotiating the ungraceful can have the presence that this video has, and keep both the ephemeral and the permanent in sight.

from “Joan Jonas: Merlo”

here there’s no bird in sight though dogs bark, drawing

the evening out into a dark that carves into things

that slip from thing to hand to chance. I didn’t see a major

difference between a poem, a sculpture, a film, or a dance.

Sometimes the birds are simply drawn. Sometimes they

remain alone. She often draws without looking at the paper

keeping her eyes instead on the model somewhere

farther the barking dogs out of sight to the left are haunting

an echo that creates a third dimension within the screen the barking

continues to make its own rhythm inherently a part of the

night. I used to work only at night. “Did the sound

carry over the water?” We know that a river runs down there at the bottom

of the valley a strip of darkness moving swiftly through hills

merlo, merlo

black among its wing

Among the animals throughout her work moving swiftly through

mythology and fairy-tale every animal is in fact its own

myth, hauling centuries along inside it. And every dog is, in fact

also a path. And the barking, a gong as a crowd as a shroud

hidden in wind.

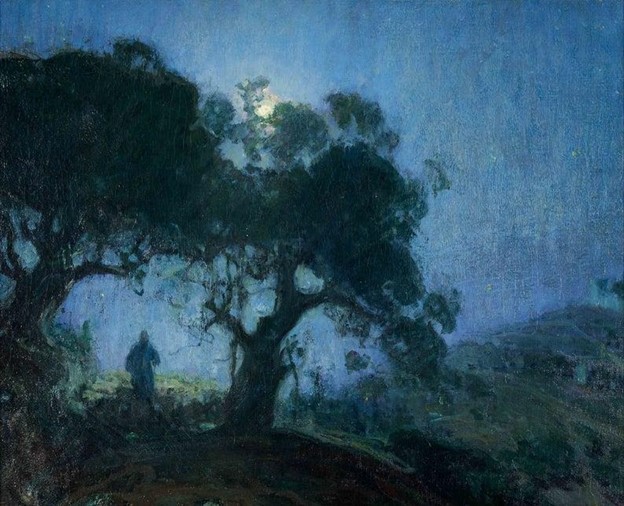

In many of his late works, Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937) chose an unusual approach to landscape—the night. Perhaps because, as the son of a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, he had a strong religious upbringing, he often depicted biblical scenes, setting them in richly shadowed and nuanced moonlight. Born and raised in Philadelphia, he moved to France as a young man and stayed there for the rest of his life, though he traveled widely, particularly throughout North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean. I was struck by the fact that, while so many painters spend ages seeking out the perfect light, Tanner was, in effect, seeking out the perfect dark. I love the way that he flipped that cliché on its end and found a different quality of light that is, in ways, more luminous than the sun. He makes us think about the difference between luminosity and light—and demonstrates that the former is about illumination radiating from a within rather than coming from some outer source.

from “Henry Ossawa Tanner: Night Over Night”

Night, in which things become unfixed unlimned; his later

paintings, something flies apart in them as something flies within

Tanner, a quiet man, for whom painting a landscape was a mode

of displacement, a form of travel, not only from one place to

another, but from self to self, one hand on the handle of a door.

You paint the handle, and then you open the door. Le Touquet,

c. 1910, on the Normandy coast, near their house in Trépied in

the moon in the clouds over the azure is such an ocean heralding

form. Two people are heading home beneath two trees that are

still there, now leaning over two other people, protecting them.

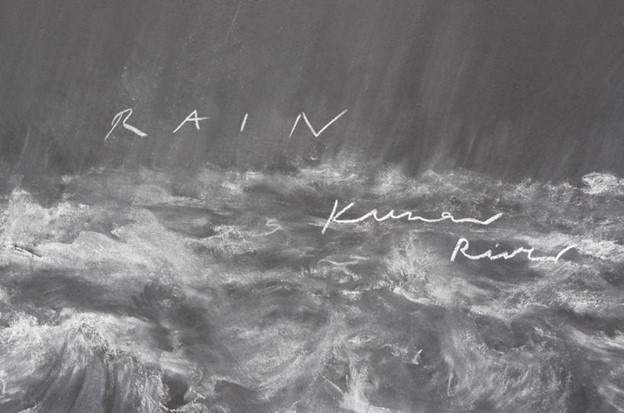

Tacita Dean (b. 1965) is best-known as a filmmaker, but she’s worked in a number of other media, from the retouched postcard to alabaster tracings to catalogues of three- and four-leaf clovers. Some of her earliest works, some of which I refer to in this piece, were done in chalk on huge blackboards in her studio. The most striking thing about chalk as a medium is its fragility—it makes fragility into a call to attention: be here now, or you will not be.

And that’s its power—it manages to convey the fact that, if you don’t pay attention, it’s not it, but you that will not be. Dean conveys in these pieces the constitutive force that all art is; in constructing its audience, any work of art constructs each individual viewer, and then reconstructs that viewer as part of an affective collective.

I’m also drawn to the way that both Jonas and Dean have used black and white—that stark contrast has important political reverberations, subtly pointing to the false binaries that condition contemporary social discussion—and the way that each of them employs greys is doing a lot of work in these realms.

Tacita Dean’s focus on the sea, which is more pronounced in her earlier work, seems to offer another angle on the ambiguous in-between that the grey opens up.

from “Tacita Dean: In Light of the Sea”

“has receded into a further past than is strictly chronological”

will rain again and the pool of light down will rain

and will I face and will I walk on back

across the plain of water—sketched, minute, precise, a seascape

in-finite, a glint of flight, a flint struck, run dumb alit or just the

white voice of the white noise of the sea speaking across

the sea

is always across.

Does the boat make it or not?

A seascape, unlike a landscape—though they both function by

creating more distance than the scene could actually hold—

makes you think that you’re outside the frame, but this is an

illusion, and you think that that’s what soothes you, but it’s not;

it’s the rocking of the clock in the sea.

Christo (1935-2020) and Jeanne-Claude (1935-2009) had a practice based on embracing the earth as literally and as figuratively as possible. By wrapping islands and coastlines or, in this case, running a white fence over miles of rolling California hills, they seemed to thrown their arms around land in a gesture of honor and respect emphasized by the lavishness of their means and scales. I found this piece particularly stunning because it manages to capture the motion of the earth, reminding us that, though following a geologic time too slow for our senses, these hills are still rippling, still in a process of self-creation. Though all their work has undertones of ecological activism, this piece in particular emphasizes the sovereignty of the earth and its status as a living being with full rights.

from “Christo & Jeanne-Claude: The Running Fence“

How quick a streak might cause a heart—that a heart might see

a quick streak take off from it, the heart already thought out

in light. It seems that the eye can’t help but follow any bright

extension seems to leave all boundaries in shreds.

And then there’s a long low gravel sound, calm in the face of the

equally rolling sun. The Fence is the gesture that changes the site

from land into landscape; by placing a work of art in it, it’s

suddenly apparent.

And you, writing out the museum label, list the materials: light,

time, and weather, all the while thinking of the unidentifiable

animal that you saw last night silhouetted against it.