At the Intersection: Aaron Shurin talks with Brian Teare about Unbound: A Book of AIDS

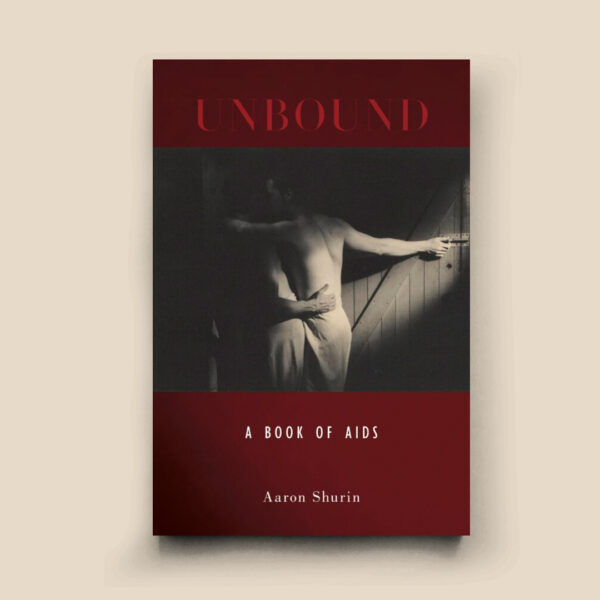

Today we celebrate the publication of Unbound: A Book of AIDS with an interview between two queer Nightboat authors, Brian Teare and Aaron Shurin. The two engage in an evocative conversation that runs the gamut from queer ecstasy and poetic aesthetics to the ramifications of AIDS and the enchantment of language. As Shurin says, a poet can “awaken the facts so that the reader might participate as one of the community in peril and in grace.” This compelling conversation between Teare and Shurin does exactly that.

Brian Teare: I’ve always loved how deeply intertwined the physical artifice of drag is with an equally artificed language, the vernacular you aptly called “American Florid.” The way you read drag names as marking “the self as a multitude and gender a performance” rhymes deeply with a passage from your elegy-essay, “After Genet: 1910-1986,” which describes an aesthetic “in which language, gesture, and dress combine into a costumed drama of social forces intimating selves.” This sensitive reading of Our Lady of the Flowers certainly justifies grouping your meditations on Genet with your meditations on drag, all of which stress the radical possibilities inherent in applying the aesthetics and politics of the performance of gender to a poetics of language. But I can’t help but think Genet’s books also dwell on the abjection and violence he saw as specific to a criminal and queer sexuality. “He saw in sex, violence, and even gender disarray,” you write in “Smoke,” “a political revolutionary force.”

Given that your poetics tends to thrust (ahem) toward rapture by way of erotic energy, toward an ever-deepening enchantment by way of artifice, I’m wondering what place (if any) you’ve made in your thinking for the revolutionary potential of the second term in Genet’s trinity of sex, violence, and gender disarray?

Aaron Shurin: I often think of those elements being intertwined in Genet (as well as life.) I think of the paradigmatic gesture (I’m crawling through memory here) in Our Lady when Divine, I believe, enters a café and someone calls out in a drunken slur, “homoseckshual” (something like that in Frechtman’s great translation; we would probably say, “fag!”) And Divine’s inimitable response is to take out her false teeth and put them on the top of her head like a crown (Lo, queen.) I think I’m not making this up, but if I am, it’s pretty great isn’t it? So the violence of the slur is met by the ecstatic transubstantiation into — well, as I say elsewhere in that essay — a Thing. A crown. A queen. You know when I was young I used to think I was, and was going to be, a dark poet, a kind of Baudelairean kin, swimming in the pools of abjection. And there is plenty of abjection in my earlier poetry. But I seemed to veer towards a more celebratory poetics as time went on, and here I stand, ready to plug myself into a socket and shimmer. On the other hand, there is Unbound: A Book of AIDS, which can only be seen as transpiring within both the violence of the viral attack, and the violence of the inadequate and criminal civic response. And if there, again, I may be most taken by the transcendental acts of my friends, nevertheless the sorrow and fear and horror of the epidemic — the violence — are the ground from which these acts arise.

In Unbound it begins with the rage of Full Circle and its revolutionary call [“So I do not propose “City of Men,” or any other creative act, as a substitution for sex. I do of course propose safe sex — medically safe but not politically safe, not socially or even psychically safe. And toward the day when the Human Immunodeficiency Virus is consigned to the dustbins of history, I’ll dream — with Whitman — “Unscrew the locks from the doors!/ Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs!”] and carries through the ferocious elegy of “Human Immune.” [“Pain is healing me into submission, he wrote in his journal the secret of the universe, hell is round. You flop and thrash in fact.” And, “I take the oath worthy of your friendship exterminated in me. The lancing pan stuffing me with bucks and thwacks to distill soul’s fuck…” And the final horrific anal-oracular plea, to give voice to the disappeared and disappearing, “Come — this’ll serve as a bed — fuck my ass into my mouth.”]

It occurs to me that violence may be enacted in my poetry as elegy, and for all my twinkles it may be as an elegist that I am most seriously at work. That’s certainly true of my two longest poems, “Human Immune” and the new piece “Reverie: A Requiem” [Now “Shiver” in The Blue Absolute.] which just went up on the Duration Press website. It’s an elegy, of sorts, for the transfigured city of San Francisco [“She lists in sequence the towns burned, the cities under water, what she remembers and what she’s been told, what she’s read in The Book of Slaughter and The Book of Stains, The Codex of Compton, // and the Index of Vanishing Holes.” And “It has to be collective, it has to be grabbed by the throat and shaken.”] I hope I’m not twisting your intent too much, but yes, perhaps I see in poetic elegy the dark flower of violence. I guess we could call it a “fleur du mal.”

BT: You intuited so beautifully what I didn’t say, and that I was thinking in particular about the relationship between queer ecstasy and queer abjection in your work, particularly when it comes to Unbound: A Book of AIDS. And I love the link you’ve made visible between a crucial AIDS-era text like “Human Immune” and the new poem, “Reverie: A Requiem.” But I was also thinking about the letters of Duncan and Levertov and the central role that evil takes in his critique of her work – how Duncan believed, as he told Levertov in objection to her anti-Vietnam poems, “The poet’s role is not to oppose evil, but to imagine it.” And I was also thinking that, as you yourself suggest, you seem to be up to something different in Unbound, whose essays also contrast dramatically with a poem like “Human Immune,” which was a part of the original book, but isn’t collected in The Skin of Meaning. Re-reading the essays without their companion poems and dipping back into the original printing of the book, I find myself confronting a knot of related questions: what work concerning AIDS did essay allow you to do that poetry couldn’t, and vice versa? In another poem from Unbound, “The Depositories,” you write, quite bitingly,

The enemy personified the nation. A fiction or series of fictions

exploding through with smoke, pouring sweat. At the foot of

a tree hands stuck in the dirt. Once in a while they hold on to me.

I find this tone and the tone in “Human Immune” distinct from those of the essays, and of course the disjunction between sentences is also greater, but, given your subsequent parallel practices as prose poet and essayist, am I making too much of such distinctions? And lastly, I’m wondering about your relationship to Duncan’s argument about poetry and evil, if you have one. Do you think AIDS necessitated a radically different take on the moral imagination than the metaphysics and cosmology of Duncan’s Vietnam War-era oeuvre?

AS: What a beautiful thorny knot of questions. I know these cut deep for you, as someone who has written so eloquently and movingly about AIDS. (And in fact most of the other themes and topics we’ve been covering.) First, the exclusion of the poems from the reprinting of Unbound in Skin is, of course, just because the latter is framed as essay writing. It was an artificial distinction, but paying attention to it as you do does, in fact, reveal a tonal and topical difference between the poetic and essayistic work. Then, of course, the challenge of the essays was to adhere to fact to a large degree, and that was (besides the pure exigencies of nonfiction) because I felt a particular duty as witness and chronicler — of both the highs and lows — a kind of Tiresias/Cassandra mix but with eyes trained on the present — in the face of what amounted to the eradication of cultural and social history, and also a responsibility to give proper respect to the men I knew who had struggled with and even transcended the evil that was the epidemic of the 80s and 90s (especially in San Francisco.) As I say in my new intro to the material in Skin, I needed a prose-writer’s scalpel to peel back the layers of information, and name and frame the details, but a poet’s heart to make sure the information gathered itself towards meaning: to awaken the facts so that the reader might participate as one of the community in peril and in grace. A simple task, right? I (felt I) needed to invent a new prose (for myself) that could admit the lyricism that would free the prose from single-mindedness. And maybe that idea of single-mindedness was akin to what Duncan objected to in the Levertov poems and called “opposing” evil.

Hard as it was to write the essays, it was much harder for me to find a way to write a poem—and “Human Immune” was the culmination of many years of frustrated attempts and non-attempts. As you know, the poem was released by dream language, which was offered to me on waking as the phrase “Hell is round.” The difference between the poetry and the prose? If I were writing an essay, the goal would be to explain “hell is round;” if I were writing a poem (as I did) the goal would be to perform “hell is round.” So I performed “hell.” I think that is pretty close to Duncan’s idea of imagining evil. The responsibility of “hell is round” and so of “Human Immune” was to give full vent to my broken heart and so break the hearts of my readers. I wanted to shake them from complacency so that — well, so that they might participate as part of the community in peril and in grace. Perhaps, then, these two routes did have the same aim, to tell the unspeakable truth that was so invisible to so many, and rouse the conscience of a nation still mostly asleep.

Was that so different from the Vietnam era’s moral complexities? Maybe not. And one other point: the essays necessitated a certain distance, since as an HIV-negative man I felt it incumbent on myself to let others speak, as it were; but in the poem the imagination permitted me to speak from multiple points of view, including the infected. I had always said anyway that though I did not have HIV in my personal body I did have it in my social body, and I could say that the poem has the virus in it. If we take Duncan’s cue that poetic imagination is also a duty (“the poet’s role”), then perhaps the distinction of the AIDS-related poems is that they’re not just about the disease, they suffer it.

BT: Thank you for untangling the knot of questions I offered in response to Unbound, the work of genre, writing AIDS, and the moral imagination. I especially love the distinction you make between the essayistic tasks of recording and explaining a fact versus the necessity of a poem’s enactment of it. Hell is round: “Human Immune” so clearly performs the dream’s message with a panicked extravagance as persuasive as your most gracefully phrased and paced essay. And while we’re on the subject of Duncan and Levertov, in the marvelous “The People’s P***k: A Dialectical Tale,” you encourage readers to see your work as the synthesis of their thesis-antithesis relationship. “I’ve only ever counted such dual inheritance as one of extraordinary luck” you write, “their immediate graces mine to learn from, their tensions played out in the parameters of my work.” I’m struck here, as I am elsewhere in your essays, by the emphasis on synthesis over antithesis, a poetics of saying and and and and and, no matter the tension produced by embracing conflicting imperatives. For instance, instead of vilifying Levertov for the revelation of her homophobia, you mark your disappointment with her limitations and honor both the grace and tension she and her work offered you. Readers of The Skin of Meaning can see this dialectic played out multiple times, as between New Narrative and LangPo, for instance. As you wrote so beautifully in an earlier answer, “It wasn’t black or white for me: I took what I needed, and for the rest rather than rejecting it I tried to propose an alternative (or plural).” Of course, this emphasis on synthesis can be read as another aspect of your lifelong vow to aesthetic maximalism, but there seems also to be an ethics at the core of this pluralist stance, particularly given the polarizing enmities at work in the poetry world. Duncan, of course, was himself justly famous for such enmities, so I’m wondering who, if anyone, modeled such pluralism for you?

AS: It’s hard to know when we’re talking about the work and when the life. Duncan who, as you say, was so contentious — and with nobody so much as his peers — in the social and esthetic world of poetry — an absolutist, in many ways, just as he saw Denise to be — was, in the poems themselves, a polyvalent collagist of eras and modes and origins. And the figure of the Grand Collage was, for him, the highest order of things. My immediate nuclear family, which was a family at war with itself, engendered endless ultimate pitched battles and serial owning and disowning. I was, in general, the lesser warrior of lesser battles, and to some degree I saw the owning and disowning and owning [literally you are not my son or you are not my father] as a kind of endless thesis antithesis for which I imagined the synthesis, since I was pulled, like my mother, by both ends of the tightrope. At worst this represented a retreat from moral consequence; at best it was a reconciling of opposites, and a recognition that the art of life is the art of contradiction. As I grew older I came to believe that the art of life — and, sure, the life of my art — was, in fact, in sustaining contradiction. The poem itself was a dynamic influx of contending forces, and this made it an active, almost alive, thing, pitched at the edge of sense and sound being transferred continually into meaning. Models for such pluralism? Most of my literary heroes, I think. Whitman, of course, not just with his avowed cosmic selfhood and I-contain-multitudes identity, but with his grandiose civic vision turning on a blade of grass, and his drama of democratic communalism laid over the sick ravages of manifest destiny and proto imperialism. Or Proust with his gossip’s heart and scientist’s calibrations, his romance of class parsed by his romance of behavioral psychology, a devotion to those he would peel like an onion. Or Colette with her gender dynamism, her broken heart and mad love matched by an unrelenting eye for truth and lies; or H.D.’s rose, trembling in a sea breeze that was simultaneously a mythic and spiritual wave: “And every concrete object/ has abstract value,” she writes, “is timeless/ in the dream parallel.” So she saw the opposing forces as coexisting, almost as of dimensions. I guess that pretty much sums up my own pluralistic vision, where contradictions are dynamically sustained in and out of time. And the tensions themselves are the “livingness.” The stretch or pull of balance or co-existence in synthesis is generative: It suggests that meaning can’t be rigid; it has to keep moving. By “sustaining contradiction” I mean the work lives in a kind of shimmy between or among the various contentions. All the powers of poetry I can harness coexist and/or combust continually, i.e. “an ever-twinkling ceremony of feathers and light.”

BT: How to isolate the effects of a politics from the affects of friendship, how to isolate the effects of gender or sex or sexuality from the affects of experience, the materiality of embodiment? These questions point to moments of disjunction between language (rhetoric) and our bodies, moments to which, in my reading at least, you have largely dedicated your career. Your poems often enact the exact moment where embodied experience ceases to be contained or policed by language and its ordinances of grammar – in that instant, your poems go all gorgeous with non sequitur flourish and lyric overflow, ecstatic stutter and delicious melisma. And I love how the title of these essays, The Skin of Meaning, insists on a conflation language and body. Indeed, it’s a central gesture of your poiesis, to posit a perpetual analogy between the textual and the physical bodies, which indeed blur together in a sensual unboundedness. Though those moments when language fails our bodies can also be deeply unpleasant, you argue in your recent essay “Prosody Now” that prosody “is the face and form by which the poem falls more deeply in love with meaning…and the body through which writer and reader are drawn into the embrace.” I never cease to be astonished by this idealism, this faith in language. And I’m wondering how you might figure the relation between prosody and, say, the work of elegy, or between this loving embrace and the kinds of violence we spoke of earlier – shame, homophobia, AIDS?

AS: Oh, Brian, your reading of my work makes my own work lucid for me. Prosody as the body of meaning, the means of sensual apprehension of language and the throbbing grid of intellection: There’s no privileging of content in this dynamic. It doesn’t matter whether you’re writing about yesterday’s shimmering mackerel sky, or today’s lunatic political maneuver, or the loss-out-of-time of a generation stampeded by AIDS — the urgency of the work to take shape via the magic near-embodiment — the formal contours or inherence we call prosody — is identical. The poem as howl, say, needs lungs that are capacious, a skull that can resonate, a voice that can be thrown. The writer needs that from the poem, and so does the reader, who reads because she seeks knowledge of the howl, experience of the howl.

In “Reverie: A Requiem, “ for example, it wasn’t till a month-long investigation into stanza formation, culminating in the invention of a stanza that was simultaneously justified and versified — the lines of the stanza were set as prose but the end of each stanza was also a line break… it wasn’t till the poem found that shape that the second and third parts arrived in a rush and the full arc of the poem came into view. The poem wanted to inhabit a dual city of circumstance and memory, the glittering city that was, and the city immediately on fire threatened with extinction. It needed the flow of rage on one level, and the disjunction or trigger to switch to the alternate current where another river flowed, with “my eyes clear and the air clear // and that blue-jewel horizon and my pledge of intent with my heart clear in my deep-breathing chest.”

Every writer has to be an idealist to imagine the possibility of such enactment: you dream it for yourself and you dream it for the reader, that you might find the means to give meaningful shape to your shame or ecstasy, and that the reader might also “be drawn into the embrace,” so that shame might live to be expiated or ecstasy ignited. The reader, too, is possessed of such dreams, and perhaps now it makes sense to call prosody not a body but a book, to describe the agency of such interactive transmission as a Book of Dreams.

Maybe that’s the culmination of the “analogy between the textual and the physical bodies”: the return of the figure from body to text. Which book is in your hands, of course, and your astonishment at my idealism matches your own idealism that continues to write itself forward. Perhaps it’s what you meant anyway, but for sure that we share. Dream, book, body, shame, or flourish: Language admits us such strange enchantments we seize on and inhabit as a poem.

Excerpted from a longer conversation between Shurin and Teare that was published in The Conversant in 2016.