An interview with Camille Roy and the editors of Honey Mine, Eric Sneathen and Lauren Levin!

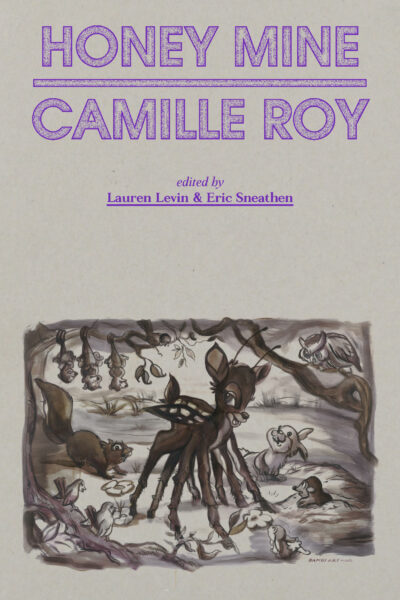

Today on the Nightboat blog, we’re highlighting the soon-to-be-published Honey Mine by Camille Roy (ed. Eric Sneathen and Lauren Levin, pub date 6/29), a book of collected stories written roughly between 1985 and 2018. A crucial figure in the intellectually heady and sexually charged New Narrative literary movement, Camille Roy continues to be an inspiration to many lesbian and queer experimental writers. For the Nightboat blog, Roy and editors Eric Sneathen and Lauren Levin discuss the making of Honey Mine, its formal qualities, and the histories and experience that inspired its writing.

_______________________________________________________________________

Eric Sneathen: What is Honey Mine? Truly, I’m not sure I’ve read a book like this one before, as it is a collection of work that has become exceedingly rare as well as a selection of your essential prose writing as well as a sampling of previously unpublished work. It’s also not a memoir, but it’s structured somewhat like one, with the iterations of the heroine moving from a childhood in Chicago to college and then on to San Francisco, much like you did.

Camille Roy: It’s writing that wanders between fiction, theory, meta fiction, cultural critique. It uses experience as material so it may at points appear like memoir, but it is not memoir. It’s all in the service of making the work and a context for the work in the same gesture. The reason this was required is political; without this, the work would have been incomprehensible or simply unable to emerge. Honey Mine is a candid investigation of the unrepresentable.

ES: One of the essential components of Honey Mine is the two longer stories that comprised Swarm, which was originally published by Bruce Boone and Robert Glück’s small press Black Star. Can you say more about that book and its publication history? I also remember when you talked about an idea you have for a novel, which you described as “Dickensian.” Some of that work is represented in Honey Mine, complementing its universe of sex workers and revolutionaries.

CR: The novella “The Faggot” came to me as a whole narrative, its own creature so to speak. I had the idea of this story in relation to a SF Arts Commission individual project grant. I was trying to figure out how to get someone or something to pay my bills while I wrote. Since the project I was proposing to the SF Arts Commission was required to include presentation to the public I got Bob to agree to publishing the writing as a Black Star Series book. Getting the grant enabled me to write “The Faggot.” This was followed by design and publication of a small print run. The design process (with Jay Schwartz) was fun. The book is nearly as textured and colorful as a rug.

“Perils,” the other novella in Swarm, is a piece set in the Ann Arbor, Michigan community I came out in. The story is a weird hodgepodge of physics with an anarchic community of lesbian sex workers. It is set in the 1970s, which is an interesting period to me: a sloppy and degenerated version of the 60s yet definitely still revolutionary. Despite being extremely politically active I don’t think the Ann Arbor community has gotten much artistic representation (although there are great archival collections, for example Gayle Rubin’s archive).

The grant for this work was designed to support underrepresented communities. In the broader culture lesbians were invisible and without cultural currency. (The issue still exists but in a less extreme form.) Also, the politics of feminism made the representation of outlaw women a little problematic. Finally, lesbians were in the peculiar situation of being overrepresented in straight porn and underrepresented everywhere else. (Still true.) The result is that this material didn’t fit comfortably anywhere.

ES: What was the editorial process like for you? It’s strange, perhaps, to think that a book like this even needs editors. And yet working on this book with you since 2017 has been such a collaborative endeavor, with all of us bringing something to its scope and particularity. We both remember your readings at the New Narrative conference in Berkeley and having a lightbulb go off that it’s beyond time that everyone could experience the power of your writing.

CR: It was fabulous to work with such astute editors. With their support and input, the manuscript ended up coming together into a multi-faceted whole that was impossible to anticipate and delightful to discover. What emerged has a remarkably strong unity of voice integrated into shifts in form and content.

All of this work was in the process of disappearing (or had already disappeared). I would not have initiated this effort on my own. In a larger context, the queer / lesbian cultures and communities of the book are subject to disappearance. They are fugitive in subjectivity and also in relation to history. It’s truly remarkable that the work has not only been preserved but further developed. Unpublished pieces were polished and brought into relation with the book as a whole (this was a particularly invaluable and rewarding aspect of the editorial journey).

When the New Narrative conference happened, where Lauren and Eric together approached me about working on this book, the identity and work of being a writer was no longer my active concern. I was on another journey (and had been for more than a few years). In this instance, I left the writing life after 12 years of mostly on, occasionally off adjunct teaching that I realized would never sustain me. So, I had taken off wholeheartedly in another direction. That turned out to be a decade long mad adventure which ended, as they do, but had many positives.

I used to interpret these changes as failures. I don’t see them as failures now. I’m a sailor, not a writer. When the voyage is over, when the work is done, I go down to the harbor and pick another ship.

That brings us to Honey Mine. We have joined together to fix it up, make it seaworthy, and take it out into the open ocean. We don’t know where exactly we’re going but we get to find out.

CR: My question for you guys would be whether there are aspects of the book which you find helped you to explore or expand your own writing practice.

ES: When I’m excited by someone’s writing, I want to consume everything that person has written, and I get a lot of satisfaction from my own writing when it’s inspired by imitation. This extra turn of mediation—inspired by imitation—is important to me, as I’ve tried to put the tools others have crafted, using them for my own purposes. In the midst of editing Honey Mine I felt this sense of permission to enter prose writing as if for the first time, putting one lavish sentence after the other. (Lavish is so Camille Roy.) Without a care for narrative, I stressed the decadent dimension of subjectivity in order to articulate a world of fantasy that I experience as always active in my life, though its events rarely rise to the level of event. I was inspired by the book’s examination of queer subjectivity—complicated, necessarily obscure, and therefore iterative. The obvious analogy is with pornography. In porn, the story that precedes the mechanics of sex ensures a porousness that invites the whole world in—strangers with unexplained scars, real views of real cities, unexplained noises emitting from adjacent rooms. The porn star, a creation of the very person performing, inhabits each new scene as if they had never before been caught up in the tumult of sweat and circumstance the porn reproduces with such tenacious consistency. I wonder sometimes how my own life feels that way: confusing yet precise. I feel incredibly grateful to your work for giving me the tools to write through my own experience.

Lauren Levin: While editing Honey Mine, I grew more and more attached to a form I think of as the Camille sentence. Like pornography or delight, I know it when I see it. It’s often deceptively clear, but its translucency glows with obscure depths. The Camille sentence has a touch of the aphoristic, the gnomic: it prefers the suggestive to the interpretable. It’s wise and brash. Mordantly witty, it never outstays its welcome. Instead, it snaps shut on its moment, then stays open in the mind. From “Isher House”: A crime is an intimate form of knowledge. It breaks you, then remains present, like the water running in the sewers. I’ve been wrestling with a prose project for the last few years. Though I doubt the Camille sentence supports commandments, I’m always mining it for clues. While I write, it reminds me to: end a bit off-balance, on one foot; maintain connection to the present and its intensities; taint my ideas with bodily residue and vice-versa. Every once in a while, one of my sentences reminds me of a Camille sentence. A kissing cousin at least. My sentence has potential. I try to coax it that way.

ES: It’s perhaps inevitable that people think about this book as a kind of retrospective, whether fairly or not. Honey Mine has that spectral quality to it similar to that of other New Narrative texts. It’s a book of fiction that represents relationships and particular conditions of social and sexual life that have passed. But I want to stress that it is also a book of the unfinished business of those relationships and the conditions that necessitated them, with all their yearning, urgency, and verve. This is a book for today at least in part because it’s focused on the body, reclaiming the body and its pleasures and the political work of understanding how we have been alienated from our pleasures and one another. Honey Mine insists that fiction, fraught in so many ways, is not an escape from our problems but a praxis of survival, self-consciousness, and revolutionary solidarity. How can fiction, especially fiction that emphasizes pleasure, help us think through our moment of enduring crises?

CR: Working on this book has led me to reflect on the formative periods that it emerged from. There are two in particular, occurring simultaneously. The first was the AIDS crisis and all the fear and grief (and activism) that rocked our social and intimate communities. The second was the split among feminists in the 1980s and 1990s between the so called “pro-sex” and “anti-pornography” camps. These were periods of crisis and conflict relating in the most urgent ways to the life of the body.

Despite being a period of trauma, those years had extraordinary community, subculture strength, and much erotic joy.

When I look at photos of gay club life from that period what strikes me most forcefully is the fierce joy and abandon, almost riotous, of the participants. I remember the incandescent Jerome Caja who seemed both alarmingly delicate and strong as carbon steel. (Alas, not strong enough to survive the era.) When he was in the room everything seemed to shake and quiver with gender fuckery.

There was also at that time a big rip in the feminist world around issues of sexuality. Arguments raged on sadomasochism, sex work, pornography, butch femme, among other topics. At least in San Francisco, this seemed to open up a space for bacchanal. I wonder whether the arguing made exploration and experimentation more enticing.

I was a bar dyke before all this gender-theory crap came along. I kissed and fucked like every other girl in my invisible world, and I stuck dollar bills in the G-strings of all the strippers in town. That world is still invisible, because I left my body there. (“Baby (Or Whose Body Is Missing)”)

Whenever I’ve read those lines out loud I’ve wondered whether they were heard as a literary conceit, a fantasy similar to Pussy, King of the Pirates by Kathy Acker. In fact, they describe the literal truth. Lesbian strippers (from the best strip joint in town), lesbian impresario, lesbian club. It was a hothouse intimacy with deep friendships on all sides.

During those years, the freedoms I played with felt natural, robust, and even infinite, at least in a lesbian context. They weren’t. Now I understand them as extraordinary exceptions to historical conditions. It’s remarkable that such exceptions can occasionally be found or even be created. In my view giving them imaginative life through fiction makes certain contemporary cultural projects feel more possible. We can be nourished by the utopian moments which glimmer in the past.