In 2020, Kimberly Alidio published two essays on the Poetry Foundation’s blog that reflected on her relationship to Language poetry, a movement whose avant-garde poetics have been dismissed by some as apolitical, academic, willfully opaque, and white. But for Kimberly, the experience of reading Language poetry, with its sonics and insistence on alternate forms of meaning-making, recalled a childhood growing up monolingual in a Filipino immigrant household, surrounded by a language Kimberly could not speak. This is an extremely common experience for children of Filipino immigrants, and as a kindred Filipino poet who had grown up in a similar environment—and who shared her own predilections toward a similar kind of poetics—Kimberly’s essay struck me with revelatory force.

Kimberly and I began working together in 2022, when I acquired Teeter for Nightboat’s list as an editor, and since then, we’ve been having an ongoing conversation about avant-garde poetics, racial identity, sound, and queerness—among other things. Something that has come up frequently for us is our shared desire to fold others into this conversation, to make it public. I was so hungry for writing like “My Native Language is Noise” until I found it; we have since heard from others who have responded to Kimberly’s essays with this same kind of excitement and gratitude.

—Gia Gonzales

GG: You have a practice of writing in response to audio recordings, and depictions of both the process and outcomes of that practice are foregrounded in the first two sections of Teeter, “Listening” and “Ambient Mom.” Would you speak to the impulse behind that practice, and how it informed Teeter? Did this practice also inform Teeter’s third section, “Histories”?

KA: I’ve been re-reading the parts in painter Amy Sillman’s book Faux Pas where she talks about writing as a visual artist. She writes about fellow artists’ paintings to articulate her own aesthetic, sensory and affective sensibility. That’s always interesting to me. But Sillman also writes speculatively and conversationally about painters’ lives, friendships, and art practice as a way to talk about both the process of making the painting and the larger world of meanings and creative possibilities opened up by painting—particularly for those of us who make art.

I think about the painter writing about a friend’s painting as a scenario in which the writing is going to be dynamic because language has to find its way in, and it can’t supplant the visual, haptic, or somatic encounter. It’s harder to get language to be that alive as a writer writing about a friend’s writing, unless the register or time period or language differs. It seemed like I could get to know more about language—my languages and experiences of them— if I wrote with sound art in a collaborative way.

Teeter isn’t a book of art writing but it is really interested in the speculative, conversational, and detailed modes of writing through immersion and curiosity about forms in sound and in memory, in the material dimensions of various languages, and finally in narrative time and history. The first section starts with poems composed while immersed in experimental music, ambient music, and musique concrete (the book’s playlist is here and here; notes on the book’s playlist will be published here).

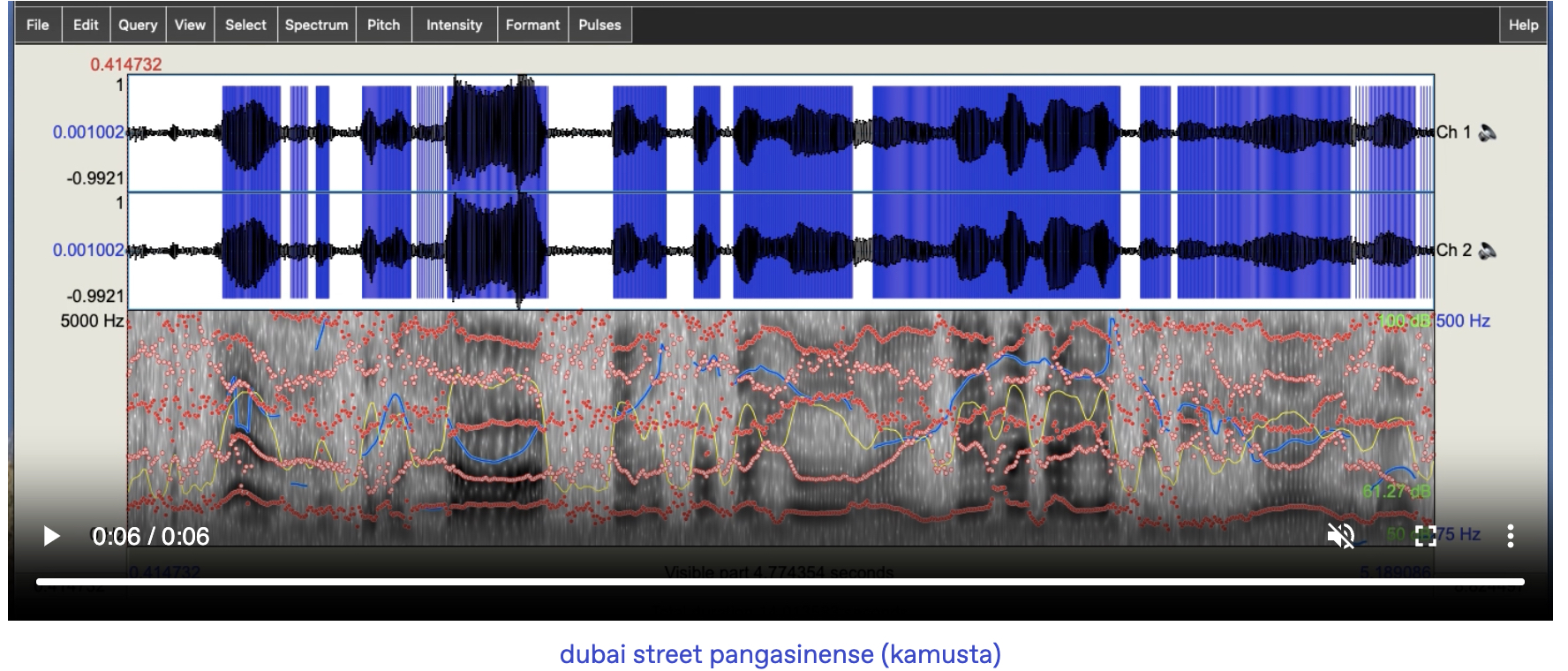

I was also interested in learning by doing, or hearing by sounding. So some poems come out of the process of recording everyday sound, and of creating audio captures of iPhone video and other media. The audio recordings I listened to while writing Teeter included those I “captured” of my environment, whether my walks during lockdown, or the audio component of YouTube videos in which people spoke Pangasinan (my mother’s language).

“Mini Reunion Batch 78” on Youtube

“Speak Pangasinan Only in Canada” on YouTube

Pressing the record button on a voice memo app moves the act of listening into the act of representing. I also used a digital audio workspace (DAW) to mix, collage, and place effects on iPhone recordings, as sound poems. And all the while writing.

The process of writing with sound has something to do with, as Brandon LaBelle has said, sound being “always already form and formlessness in one.” You can produce a shape for sound and represent listening through writing but sound will always exceed those forms. It has already gone, in a way.

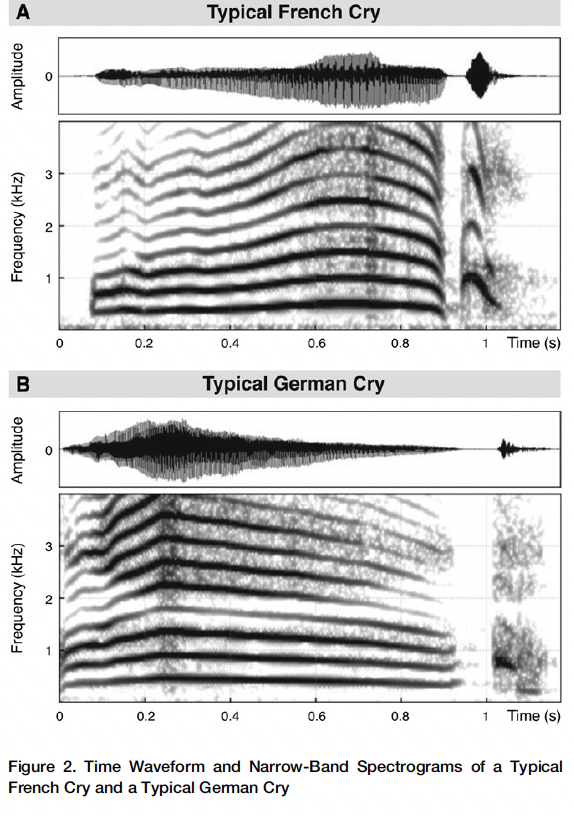

Spectrograms from Ambient Mom Tumblr

There’s so much that sound can tell you about time, timing, and temporality. Writing can be a way to catch up with what’s already in progress before it becomes a way of thinking in “real time.” The third section, “Histories,” moves the book into the prose poem form to test out this voice generated from the processes of listening and hearing.

I got into it by watching a lot of French New Wave movies featuring voiceover narration. I thought of how a voice can do one thing mixed “over” a moving image that’s doing another, and voice and the things the voice talks over and about form a conversation that is a film. And somehow a voiceover could be a form of history writing. How might a multi-directional, non-linear writing (interrupting itself, doubling back, riffing, parataxis, etc) chart a space to “tell” a story of moving from the Sonoran desert to the Hudson Valley, which I did in the Spring of 2021.

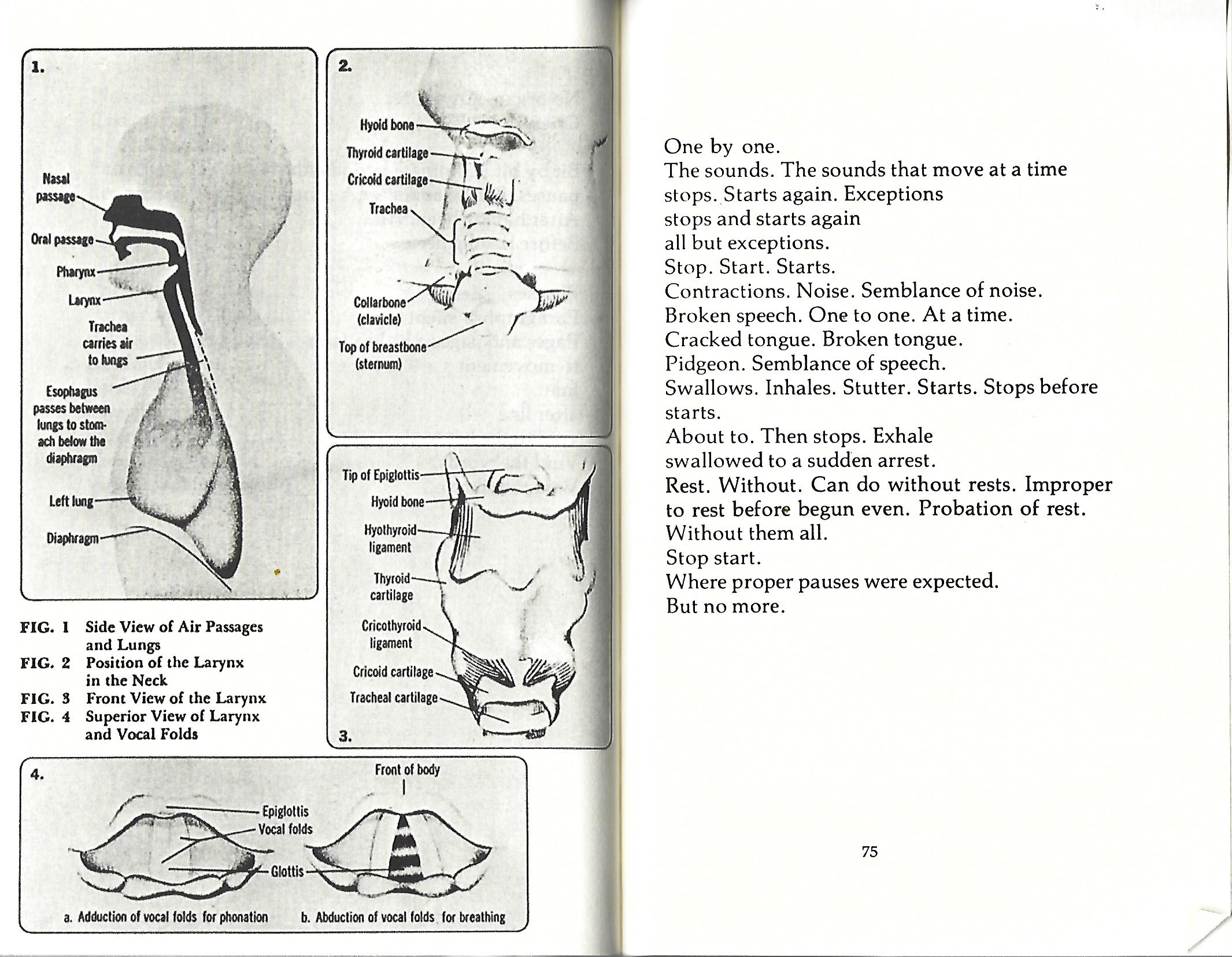

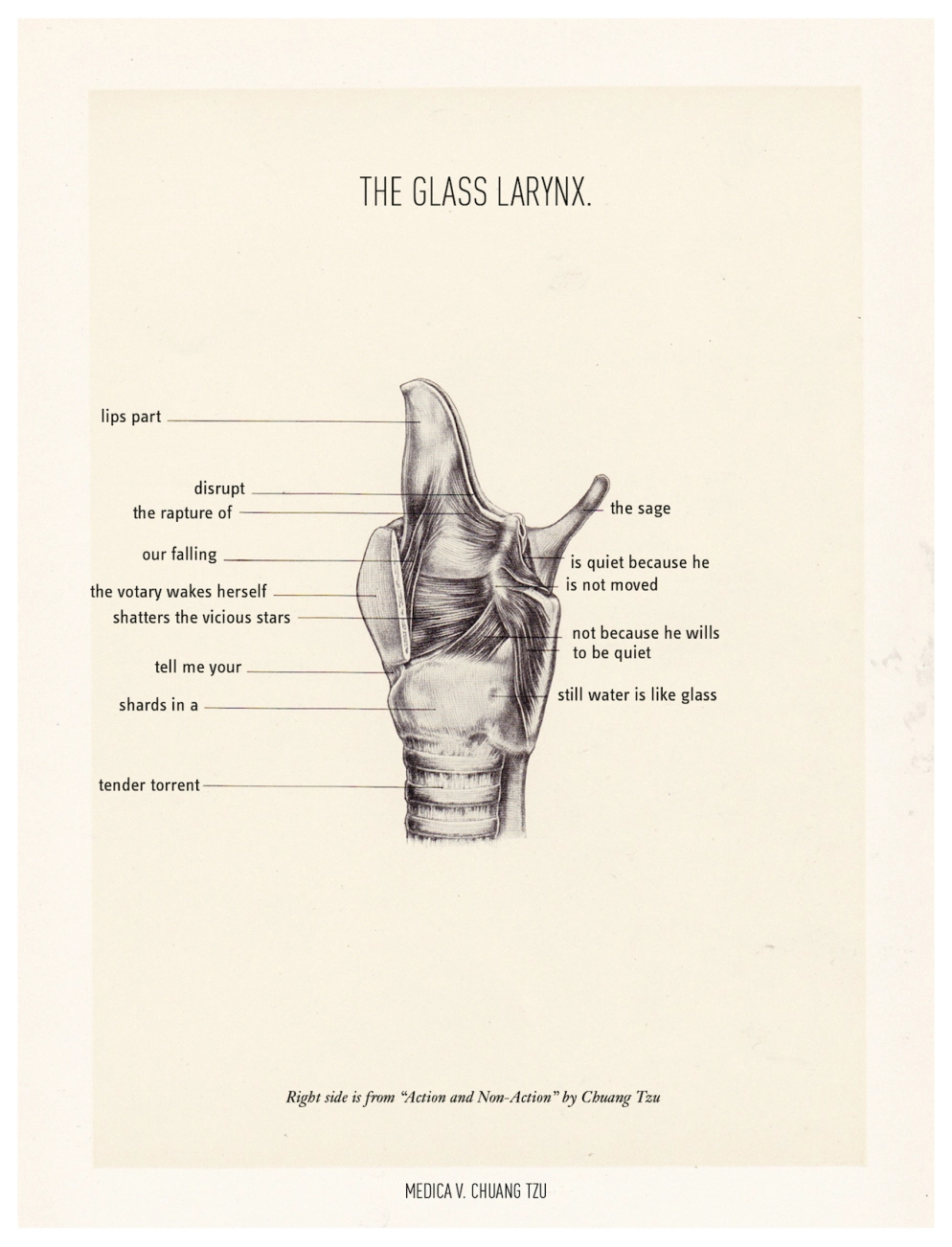

GG: I’m curious to hear more about the concrete poems throughout Teeter. Some poems seem to be an effort in recording/transcribing/emulating sound and systems of sound, while others appear almost as if they were linguistic diagrams. How did these poems come to be?

KA: Concrete poems enter the book in the second section, “Ambient Mom,” to engage with Pangasinan language. I know this language exclusively through hearing my mother speak it to family members and a few friends. I’d never seen it written so I was interested in how the written form represents what I know by hearing. And that’s where poetry has to grapple with what is visual and not. When are we reading and when are we seeing, and how and when do reading and seeing work at odds with one another?

Like sound collage making (ie, a mode of sound poetry), concrete poems are ways to represent and conduct encounters with language. I tend to zone in on one thing or another and try to take it apart, and then use writing to not just record but also conduct this immersive inquiry.

Ming-Qian Ma has said that we can’t read diagrams aloud. So do they have sound? Can you hear them? I read a lot of Johanna Drucker’s artbooks (or should I say that I viewed them?) and her scholarship on the visual aspects of reading. She says, and visually represents, amazing things about legibility, hierarchy of meaning, and power. It’s her scholarship on the configuration of letters, such as Greek vowels into triangles or the SATOR square, used in spells, and the non-lexical writing on amulets that influenced some of Teeter’s poems. I was already using Pangasinan speech and writing to invoke echoic memory, perhaps a process involving some sort of deep consciousness magic. Or you can just call it poetry. Or learning a language.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictee, University of California Press, 1982, pp. 74-75

Monica Ong, Silent Anatomies, Kore Press, 2015, via Michael Leong’s blog

GG: Would you tell us about the experience of working with two languages you do not speak—Pangasinan and Tagalog—on the page?

KA: As your question implies, “Ambient Mom” is composed of poems I wrote as I listened to speech in languages I don’t speak but heard all throughout my childhood. But we recognize and respond to sounds, intonations, rhythms, and “body language” of those speaking languages we don’t understand. That’s the ambient right there. I’ve called it emotional prosody because it’s an affective experience that over time shapes a poet’s ear. It was very humbling to represent that prosody on paper.

In the beginning, I called this kind of sound writing with Pangasinan and Filipino (Tagalog) experimental translation. Then I called it homophonic translation. But actually noting what I was hearing and remembering as I heard the sound of Pangasinan was more like interpreting. It was more like a performative adaptation of speech into a completely different world of writing.

It’s conversationally-minded, too, attuned to the ways our writing and speech calibrate different registers to hear and be heard, to work with others to create a channel of connection. What else happens in that channel, and what can happen?

I decided to use the orthography of phonemic writing: encasing sound representations with forward slashes. Lindsey Boldt is an amazing copyeditor who found Benigno Montemayor who was just as amazing in copyediting the non-standard and standard-ish writing in both Filipino and Pangasinan.

The word “teeter” appears early in the book. But now that I think about it, the experience of poetically adapting Pangasinan and Filipino speech probably gave me the book’s title. Writing out emotional prosody was like trying to relearn how to walk. I think of teetering while riding the train, the risk of losing your balance as it accelerates, decelerates, and sways.

GG: Everyone loves the title of Teeter’s middle section, “Ambient Mom”! I do, too, for a couple of reasons: I love the marriage of ambience—a genre predicated on flat, non-evocative affect—with the figure of the mother, whose presence is anything but! I also love how, in Teeter, it speaks to the process of language acquisition, childhood language development, family, and the very common Filipino diasporic experience of being surrounded by a heritage language one cannot speak. Would you expand upon the idea of an Ambient Mom?

KA: Thank you! I thank my partner, the poet Stacy Szymaszek, for the title. They say the phrase, “ambient mom,” so the /a/ and /o/ are in slant rhyme. That’s a poet for you.

There’s an absolutely poignant moment in a conversation between Momtaza Mehri and Warsan Shire in which they discuss the mothers, aunts, and grandmothers of the Somali British diaspora. Mehri talks about the totalizing love of a “surveillance network of aunties.” And Shire responds, “The women and girls who raised me were bright, wild, full of life, bitter, cruel, supple, naive, deranged and hilariously unhinged, all in ways I still relate to. I was enchanted by their rituals, while also terrified of their triggers, neuroses and bouts of violence. I loved slipping into the cracks undetected, listening all night to their stories of scandal and sorrow until someone carried me to bed.”

That string of adjectives and nouns ending in a micronarrative expresses the ambient quality of diasporic family life. More so than a flat surface, I think of the ambient as atmospheric, where you might not know for sure what’s figure and what’s ground, to mix haptic and visual terms. The topic of the “secret lives” of diasporic people who run their families in ways we may call extra is so evocative, even if what Mehri and Shire specifically describe isn’t really a direct concern in Teeter.

“Ambient Mom” evokes a storytelling space of family and identity by mixing phone call conversations, transcribed sounds and speech from family reunions depicted in online video logs, and writing about bodies conducting sound in relation to one another, including late-term fetal hearing of what is called motherese.

In this section, I hold open that storytelling and listening space without providing a voiceover narration. As I say above, I delay any voiceover until the third section of the book, which is pretty much all voiceover narration. In contrast, the ambient can be said to be an atmosphere without saying anything about, without allegory, without metaphor. “Ambient Mom” is a particular space for emergent possibilities where all these high-drama, even noisy, modes of mothering and being mothered are neither pathologized nor redeemed.

My mother comes from a large family, and a few of her brothers are heavily into loving you by teasing you without mercy. One of my beloved uncles read the situation of this phrase, ambient mom, as an opportunity to tease her by suggesting I was critiquing her mothering with that title. My mom though was having none of it. She just kept on loving the long poem that had that title and reading into the title what she was reading. Nothing was going to disrupt her encounter with the poem that came out of me. That’s literally a vibe of mothering.

GG: Other experimental Asian American poets thinking through ambience more broadly include Tan Lin and Pamela Lu—do you think there is something unique that ambience can offer us as a framework for thinking through Asian American identity?

KA: I am really careful about grounding the ambient in specific memories and queries. I’m thinking of the music video of Helado Negro’s ambient pop song, “Outside the Outside,” a home movie of a 1980s-era house party. The camerawork dances along with the room of partygoers, and all the usual hallmarks of video camera “mistakes” are there: the footage of the floor, the sudden shift to landscape mode—it’s a party! At some point, there’s a small boy, cranky and sleepy, watching from the hallway. The 1980s footage is set to Helado Negro’s 2021 atmospheric bop, which envelops the dancers and the whole scene.

I too wonder about the relationship between the ambient and identity in diasporic Asian American literary writing. I love Lu’s Ambient Parking Lot and Lin’s “ambient novel,” Insomnia and the Aunt. You and I have been talking here and there about Vivian L. Huang’s scholarship on Asian American diasporic aesthetics that go against expectations that identity-associated art provide depth, liveness, and immediacy. Identity is a form of representation in so many senses of the word—political, social, cultural. But it’s also a representation that indexes and induces sensibility and affect.

I don’t want to cede the ambient to this neoliberal era, where it gets weaponized so we can’t locate, name, or counter operations of power. Toward the end of the first section, “Hearing,” there’s a poem called, “Of leaving the language melancholia party early.” I feel that shame and loss about not speaking your mother’s language are real affective responses, and can feel like a vibe, a mood. But in literary, political, and cultural discourse, shame and loss feel to me disciplinary, and as such similar to some institutional ideas of belonging to family, ethnicity, nation, even diaspora. (Insert here a host of references on racial, postcolonial melancholia.) Anger has a slippery presence in all this identity discourse. It is all very slippery, almost ambient in that neoliberal way of maintaining confusion as a new reality we can’t possibly understand more than we think we do.

As a writer and artist, I can be curious in a way that isn’t just for the discourse and isn’t just for an individualized or collective therapeutic idea of managing identity affects like shame and even anger. I want to return for a moment where I started the interview with a scenario of a painter writing about a friend’s painting. Another memorable part of Amy Sillman’s book is how she writes on the sensory, practical knowledge the artist has of their materials. For instance, tubes of oil paint vary in weight by pigment color, so a painter eventually learns which pigment they’re holding by how it feels in their hand. This knowledge is from practice and not from learning color theory in art school.

Let’s make this a scenario of a poet thinking about language and identity. Language in the plural is our material, our tubes of paint, so to speak, that we hold in our hands. Working with or against writing systems and what other poets and artists have done with them, we learn something vital about language as it relates to identity that isn’t taught in critical ethnic studies classes or by community elders or culture workers. Or in an MFA poetry workshop, for that matter. And what poets know about language and identity that people whose institutional job or mission it is to know about language and identity do not know is in the poet’s work, in the poems.

Maybe that knowledge is ambient. Maybe it can be written about somewhat directly but maybe it goes into another poet’s practice, and into other kinds of work. But it’s there to be sensed and affected by.

There is something crucial and sustaining in the ongoing impulse to keep referring to identity in legible ways. There’s also something in the ambient that relaxes and even revels in the dissolution of the terms of identity. That’s a house party. And the afterparty!