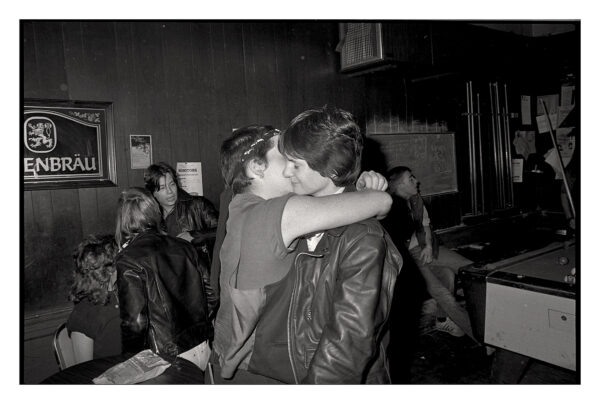

Below is a conversation between Dante Silva and Hannah Levene to discuss Hannah’s dazzling debut novel Greasepaint. Greasepaint is the portrait of a community staged in a never ending Friday night around the bar, “it’s always Friday and it’s always the bar and it’s always the 1950s, wherever and whenever we are.”

Inspired by Hannah’s research in the lesbian archive and Yiddish literature—she teases something butch from something Yiddish, or something Yiddish from something butch, understanding that the two were often in coalition: “Maybe I have written a very Jewish book that is actually a very butch book or maybe I have written a very butch book that is actually a very Jewish book… The “All-Americans” are cast as these butch-only’s, rather than butch-ands, like butch-and-Yiddish-anarchists as a kind of foil to the extra grease of Jewishness slicking back the hair of Frankie and her comrades.”

Here Dante and Hannah discuss what it means to “write butch,” performance, and the archive that inspired Greasepaint.

—Lina Bergamini, Publicity and Marketing Manager

Dante Silva: Thank you for this incredibly butch book, one that’s only become butcher with each read. You write of a butchness that’s playful, pleasurable, with performances from the characters (the loosening of a belt, a lick of the lips) that “leak out butch.”

It seems to me that you work with and against and around this word, and its pervasive usage. Could you say more about the word butch? What work does the word—and/or its absence—allow you to do?

Hannah Levene: I think you’ve picked up exactly on what butch allows me to do in writing, or insists that I do—playful, pleasurable, performances from characters. PLAY was the main word! Playful, plays, playbook, playing music, playing butch. I never approached butch as an identity like I AM A BUTCH U R A BUTCH but as this inherently mutual position which means that butch is constituted by the scene that surrounds it. Interplay, maybe. I never wanted to explain butch, or represent butch, I wanted to use it to write with. I wanted to write butch.

Dante Silva: I’m similarly curious about the prose, which has its own butchness to it. What happens when you apply the aesthetics and politics of butch to the page? How do you capture the performance of butchness, often (though not always) as something subtle, suggestive?

Hannah Levene: Esther Newton’s My Butch Career talks about the girl refusenik. And I wrote like that, kind of obstinate and unshifting, stubborn, butch. Butch becomes synonymous with all these things. Playful, pleasurable, butch. Stubborn, unshifting, butch. Wherever butch goes it pisses some people off and turns some people on; those are the same clothes and winks and looks doing both those things. It’s not just the characters that are butch, it’s every aspect of the book, that’s what it had to be. The characters to the line breaks to the punctuation—they’re all text in the end, all just print (thanks to Nightboat xxx) what I mean to say is, I didn’t write butch characters in an otherwise straight-up scene, I saw through all this reading I’d done how butch characters come as a scene and wrote a scene, a whole scene butch in every part of it. Well, that’s what I wanted to do. I wanted big butch blocks of texts which are constantly tangling themselves up because it’s not easy to stay still. By which I mean to refuse, stand your ground. And by “not easy” I mean the characters really have to try to not fall to pieces. I found that stuffing butch full of music—songs playing but also rhythm, a sense of singing, sotto voce, sprechstimme, those types of conceits—helped with that kind of “capturing” as you say. Not that the butch wants to burst into song but can’t, but the opposite: that butch wants to consume music, is stuffing it into themselves, this kind of musical inside driving those key performances or moves, styles, gestures, like a dance. Butch allows role playing to be the most authentic thing, performance, staging, lines so I let them perform I suppose. The butch in the bar is all style, language is not the chosen mode of communication so what does it mean to write “all style” and what does it mean to write a book where the bar walls have to be replaced by some other container that can transfer butch from one body to another, make it readable?

Dante Silva: At one point a character says—clad in a cowboy costume, I should add—that “if we’re going to change the world we have to pay attention to the way the world is made.” Your project does this work; it’s incredibly attentive to the making and remaking of the world, and even looks towards other ones (at one point, another character has fantasies of being probed on an alien spaceship).

A part of this is the setting. We’re immersed in 1950s New York, and yet we’re not bound by place; familiar markers of the period are present, although they almost collapse into the refrain of “ANOTHER FRIDAY NIGHT.” Could you say more about the historical context, and how you work with (or against) it? What do you want GREASEPAINT to do now?

Hannah Levene: Yeah, beyond the cover the book never once mentions where or when we are. The story of the butch on the page is often that butch is over, old news, old school, there’s a lot of butch historizing, memoirs, anthologies of memories, interviews, there’s oral histories and when the butch is found in fiction they’re often at the beginning of the story of lesbian history. I’m not trying to be obtuse in my use of butch, I think the book is very specific, but I never say the word lesbian. There was something about untying, just for a second, the butch from anybody’s history but their own (whoever they are and whatever ownership is). The story of butch in the bars is framed as pre-political proto-lesbian soon-to-be liberated by lesbian feminism and then revived or restated in the nineties but this is a white-washing and a delineating of something which never went anywhere and was never without politics. I didn’t have to imagine something new to fill the bars with Yiddish anarchists and unionized musicians. Stone Butch Blues is arguably mostly the tale of a unionized factory worker! Greasepaint wasn’t written to disprove anything, I’m not interested in writing for posterity or proselytizing, I am interested in writing and the relationship between butch and writing and the way that butch messes with time by taking time with it wherever it goes. Always over. Over and over again. Everywhere. That’s fun to write with. I had that thought clearly at some point, that the butch takes the 1950s with them wherever they go, plowing through time and churning it up. And that the butch brings the bar with them, so maybe they’re in the deli but it’s the bar, maybe they’re on the phone to one another but it’s the bar. So it’s always Friday and it’s always the bar and it’s always the 1950s, wherever and whenever we are. All over everywhere. Friday night was Butch Night Out, I learnt that from Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold, that’s exactly what the speaker says: “Friday night was butch night out” and Friday night is shabbat which is Friday night dinner, this I learnt from my own life.

Dante Silva: What archival sources did you look at while writing? Where did they lead you? Whose writing, if anyone’s, serves as a reference for your own?

Hannah Levene: When I tried to find butch in writing the tone of the books are already archiva;l as I say, there’s a sense that butch is being cast out and so a strong push in most of butch in writing that it must be memorialized, remembered, preserved. I read everything I could find, I still do. I’m indebted to The Persistent Desire, Boots of Leather Slippers of Gold, Lee Lynch’s novels, Esther Newton, Merril Mushroom, anthologies like Nice Jewish Girls and The Tribe of Dina. Instead of adding to those archives I wanted to take from them! All these amazing characters I found there! That I fell for! Butch is often put in writing outside of fiction, like it’s too fragile a thing to be fictional, like fiction wouldn’t be enough to preserve it. There are so many characters ready to write, with thanks to everyone before me working so hard to preserve butch but there’s so little fiction! I want fiction! I kept reciting, “turning and turning in the widening gyre” —the center cannot hold etc etc—that sense of grand poetry! The Poet! Anarchy unleashed! Capital letters, all camp. Feinberg talks about Jess going into exile after the bar scene breaks down in Stone Butch Blues, “Dear Theresa, tonight I walked through the streets looking for you in every woman’s laughing teasing eyes” etc etc—it’s that Judith Butler poetry from Precarious Life: who am I without you? When we lose someone, we lose them only to find we have a lost a part of ourselves, the narrative falters as it must, something like that—I didn’t look up the quotes to state them properly, sorry, but that gives a sense of the way these tattered lines were going through my head whilst writing, each thing becoming the other.

I read a lot of reasonably dry anarchist memoirs, lovingly put out by some tiny radical press, or self-published and touted round bookfairs, the type with 75 chapters which start with the story of a young immigrant on the Lower East Side and get to the moment they joined the anarchist movement and then go minute to minute through meetings they went to and, if you get through those chapters, to them being an old anarchist. I read Michael Gold’s Jews Without Money, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Anzia Yezierska, Elana Dykewomon, Grace Paley. The late night deli comes from these scenes—Berkman and Goldman meeting for the first time over the bedlam at Sach’s—but the cafe is a late night queer space too. Ruben’s round the corner after hours, it was another space where I knew all these types of people could/would/did/do mingle. Or all the people that are all those types inside of one body go. I read Robert Park’s book about the immigrant press, and read up about the anarchist papers. I thought about the choice of the Jewish immigrant to use, or to continue to use, Yiddish as a language of the people and to trust that the language could hold revolutionary rhetoric in it, that up and up and up sound which makes the speakers sound as though they’re going to sing. I wanted that in the book, this feeling of uprising which was all tied up with bars being full to bursting, butch bodies being full to bursting but this not bursting being the key thing, instead there’s this constant crush. Crush like = crushed in a crowd and crush like = I got a a crush on u. Mostly that, everybody making eyes at each other, making moves. Greasepaint isn’t in Yiddish but it is in it, like something is in a pot of soup. Irena Klepfisz talks about the seeing Yiddish theater star Joseph Buloff doing a performance of the Tepele Zup, the Pot of Soup (I couldn’t find this done anywhere or even a script of it but her description is enough, it’s fantastic) and I thought about the scene as the soup. The scene as a soup we’re all in has the added potential of bubbling, or bubbling over like Sholom Aleichem’s Chava thinks it might, dreaming of a day when the sun will rise and the pot will boil over and we’ll all roll up our sleeves and get to work to turn the world upside down! Of course, this is always happening, like the butch is always over.

Dante Silva: I’m curious about all the ways that subjectivities are constructed and deconstructed, and then collaged together in your work. Nothing appears as a singular, static category; you write of butch Yiddishness and then Yiddish butchness, with the two in constant conversation.

I wanted to ask about these two identities, the “butches whose t-shirts are all white” and the “Jews whose anarchism was like a layer of grease on them.” Where do you see the relationship between the two? How do you allow them to circulate and riff off each other?

Hannah Levene: I couldn’t see the difference between butch and Yiddish anarchist after a while. I wanted that to come across, that certain styles or signals can be read differently by different people. Like with Sammy Silver who’s trying to be this butch heartthrob virtuoso musician but whose mother just sees herself in, her mother who grew up an anarchist, cut her hair short, put on her workers clothes. Or how Frankie thinks she’s dressing just like her father i.e. dressing just like an anarchist but her father can’t stand to look at her. And how she acts like her father and in the bars that’s butch and in the living rooms of her childhood that’s being a comrade. It’s this kind of helix. Or how Roz is butcher because she’s the Kosher butcher’s daughter. I wanted to show butch as this repeatable thing, an endless hall of mirrors back and forward through time. Like one giant leather jacket, or an infinite rack of white t-shirts. Or endless Friday nights. A style and language transported through time. But then there’s also this sense in the book that the styles the characters inhabit are inescapable, an inescapable Jewishness, an inescapable butchness. It’s claustrophobic to look in every direction and see white t-shirts, it’s a fucking nightmare just as much as a complete dream. Both are true. None of these identities are singular. They’re all coming out of one body. Maybe I have written a very Jewish book that is actually a very butch book or maybe I have written a very butch book that is actually a very Jewish book. Or maybe I have written a very anarchist book that is actually a very Jewish book, or maybe I have written a very anarchist book that is actually a very butch book. The “All-Americans” are cast as these butch-only’s, rather than butch-ands, like butch-and-Yiddish-anarchists as a kind of foil to the extra grease of Jewishness slicking back the hair of Frankie and her comrades. There’s more to them that I don’t let the reader get to know, but maybe they’d be happy that they get to be just butch, all the other parts of them left outside the bar, the way they wanted.