An Interview with Funto Omojola, Author of If I Gather Here and Shout

Funto Omojola’s If I Gather Here and Shout, out this month from Nightboat Books, places Ifá divination practices alongside incantatory prose poems, to interrogate the concept of illness in a Western context. What comes forth is a ceremonious shout: “Ceremony is survival,” Omojola writes. “Survival is joy.”

In our conversation below we discuss survivance and its discontents; language, and the estrangement of language; and the different frequencies of their work (as a poet, performance artist, etc.), all of which resonate.

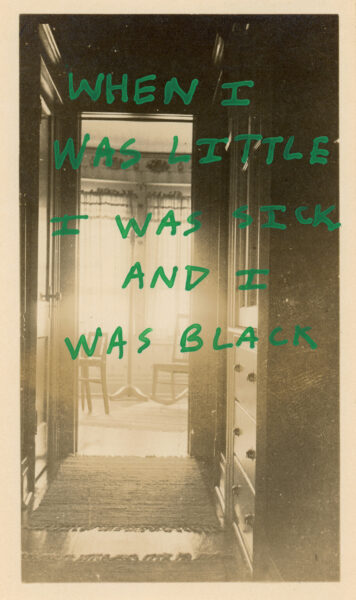

The image that appears here is courtesy of the author.

—Dante Silva

Dante Silva: I’m curious about your visual/performance art practices, and how those practices form (and are formed by) your poetic practice. Could you speak to the mediums you work with?

Funto Omojola: I’m obsessive and easily bored. So, languaging the material conditions of my life through different instrumentalities is central to my art practice. Currently, I’m writing, making collages, dancing, and singing.

When I’m using different mediums together, they have to be making separate efforts—even if they are languaging within similar worlds. For example, when I use photo and text at once, I want the visual image to do the work of bringing the viewer close, so that I can take more freedom in creating a distance with the text itself.

That said, I do think there are cultural frequencies across my work that ultimately ties it all together—even across disparate mediums.

Dante Silva: A central figure here is the Babaláwo, which in the Yoruba language means “father of the priest” or “father of secrets.” The Babaláwo has a spiritual connotation, someone sought after in moments of crisis (personal, cultural), though not always benevolent. What role does the Babaláwo occupy in these poems?

Funto Omojola: I wrote this work after being in a coma and during one of the most excruciating experiences of my life. I was mistrustful of the white excavator, looter, surgeon, scalpel wielder. And I turned to Babaláwo—literally and also as testament.

So, in the poems, Babaláwo is a site of healing, remedy, revelation when all else has failed—rupture as revelation. . . as a site of divination that affords insight into a ruptured body and place.

But it felt and feels strange to approach Yoruba medicine, the folk, traditional divinatory systems as incidental to the failure of Western medicine. So, I also think the anthropological voice that speaks about and speaks through Babaláwo in the poems, is untrustworthy.

Dante Silva: I was struck by the improvisation that takes place here, particularly with the esès—sacred verses performed by a Babaláwo in Ifá divination rituals. What led you to the form of the esè? How do you complicate that form?

Funto Omojola: There’s a tradition of inheritance that’s at the core of the esè form that’s crucial for the meaning I’m making in my poetry. In the book, the esès trace my ancestors’ histories in their bodies and in their home place of the village. The verses operate as passage places that don’t depend on discursive statements but rather hand-point, vision, and spell, outside of language. They operate on a percussive level and work by way of chants that build and accumulate, meant as a way of making the words corporeal.

Dante Silva: Illness becomes somewhat separate from the body, an in between space. How do you use (or estrange) language to emphasize illness’s effects?

Funto Omojola: These idiosyncrasies that estrange the language throughout the text invoke black practices of activating and performing language to criticize the inevitability of Western culture, e.g., the history of improvisation in jazz, etc. But also, by writing within the interstices of language in this way, I’m not only trying to map the disabling effects of disease, but also composing in the guts of flux or the in-between space that my disrupted body can occupy.