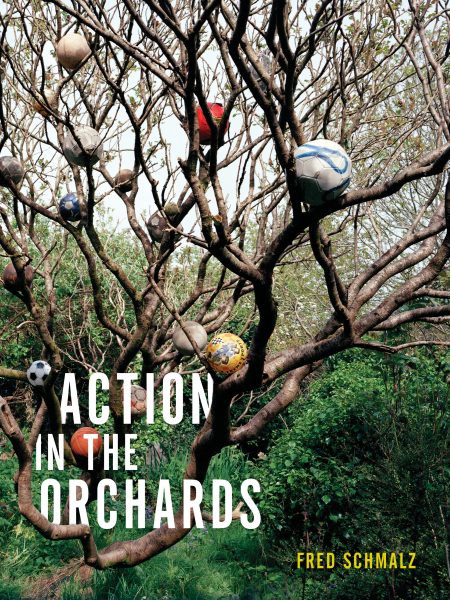

On his new collection, Action in the Orchards, Fred Schmalz remarks, “…I have resisted the tag ‘ekphrastic’ to describe the poems in the book. Sure, encounters with artworks (sometimes overt, sometimes oblique) happen. But they serve more as catalysts for other connections than as conceits for the poems.” In further flourishing and celebration of that quasi-ekphrasis so indelible to his new book, Fred considers the spaces and objects in which Action found its kinesis.

—

Because the book focuses on encounters with art, art-making spaces or art-presenting spaces (the studio, the gallery, the museum, the performance space) seem readily available in the works. When I was writing the poems, I found myself interested in how the street can act as a counterpoint and an informant to the encounters with those art spaces.

So for example in the poem “Studio Museum,” I’m thinking of the street as a space to refract the intentions of the art within the walls, or where the echoes of Glenn Kaino’s “Bridge” installation ripple onto a warm afternoon on 125th St. The poems become less about what happens inside the gallery or museum, and more about how the gallery is one experience in a broader set of relationships or a constellation of instances.

This is why I have resisted the tag “ekphrastic” to describe the poems in the book. Sure, encounters with artworks (sometimes overt, sometimes oblique) happen. But they serve more as catalysts for other connections than as conceits for the poems.

I think of the bed as one of the daily use objects that relates very closely to how I write through my own experience. I have long had an interest in beds as both daily use objects and spaces of opportunity and incident. I also like to think of them as maps to the history of our lives, if we care to trace back rest-by-rest, day or night, home or away. They may host many of our rites of passage: conception, birth, the first flittings of consciousness, dreams, sex, illness, death. They are intimate, inert, anonymous, transactional. If we feel sick, we go there. If we stay there too long, we feel sick. Beds are, in some ways, both welcoming and resistant to our encounters with them.

In “I am a dead artist,” the speaker has a hard time staying still in bed. In “Family ghosts meet the invention of the fuse,” the subject of the poem is pinned to the bed by a specter. “Upbringings” begins with a litany of mattresses. I saw this as a way of engaging with the rending (and rent) nature of my own experience at the time. It felt like I was living across these objects, which I may not have been cataloguing, but which were nightly registering my impressions.

As poets, I think many of us are aware of how sometimes our images get out ahead of us, and it’s only in retrospect that we start to see some of the patterns of objects or places develop. One element that kept returning in these poems, that I only saw in retrospect when they were being gathered into the book, was salt.

This noticing gave me an urge to understand why it were there and how it informed the poems—even those where it doesn’t appear. I begin to see salt as representative of survival and depletion, of wound and human need—the need for faith, for passion, for intimacy.

Salt also relates closely to one of the central aspects of my writing practice which is my running practice. This practice is not an object per say but a recurring occasion. Distance runs are both meditative spaces and opportunities for incident. Running is a constant happening-upon of everything in your path, for better or worse. You can get lost, panic, and return. You can fall apart physically and still need to find your way through. The incidents are impossible to predict.

For example, last summer, deep into a very long run, my training partner and I came upon a harbor where a small boat had exploded seconds earlier, killing a man, littering the roadway above with wrenches and sockets from a tool box. It was horrible, visceral. We were covered in our own salt, slowly caking on our bodies as we stopped and stooped to clear debris for the emergency vehicles.

While salt and the bed and the street feel archetypal, there are also specific spaces that appear in the book that have a broader resonance for me. One of those is the semicircular room in the Brandhorst Collection in Munich where the 12-panel Cy Twombly work “Lepanto” is displayed. What is most fascinating to me about the space, and I think it speaks to any encounter with art, is that it is impossible to see the entire Twombly work at once. The first and last paintings in the sequence are essentially 180 degrees opposite each other, so wherever you stand you’re always taking in an incomplete view. There’s a beautiful poetics to this frustration. I see it as a parallel to the access and provocations of the kinds of art that attract me—that we “conjure and disappear” into art, that there is an ineffable quality to it at its foundation.

That idea of a conjuring and the residue of resonant images is something that fascinates me. The images and objects in the book are often things that have been seen, forgotten, and then recalled when catalyzed by other occurrences. In “Door in a bath,” the lines “a suitcase / opened flat / inside it rectangular lawns” is one such image. This image came from a dance performance by the choreographer Yasmeen Godder, which I had seen about a dozen years before the writing of the poem. I can’t recall the name of Godder’s work, or even where I saw it. But I remember it was a duet and at some point one of the dancers appeared with a brushed steel clamshell suitcase, set it on the floor, and opened it to reveal two small lawns imbedded in each side. This image has lingered in my subconscious since then. I carry it with me to think about home and travel and longing.

-Fred Schmalz, April 2019

Order Action in the Orchards here or at your favorite local bookstore!

—

Fred Schmalz is an artist and poet whose current writing focuses on textual response to encounters with music, visual art, and performance. He is the author of Action in the Orchards (Nightboat, 2019). In 2018, he was commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic as poet-in-residence for the FluxConcert in its year-long Fluxus Festival. He lives in Chicago, where he makes art with Susy Bielak in the collaborative Balas & Wax.